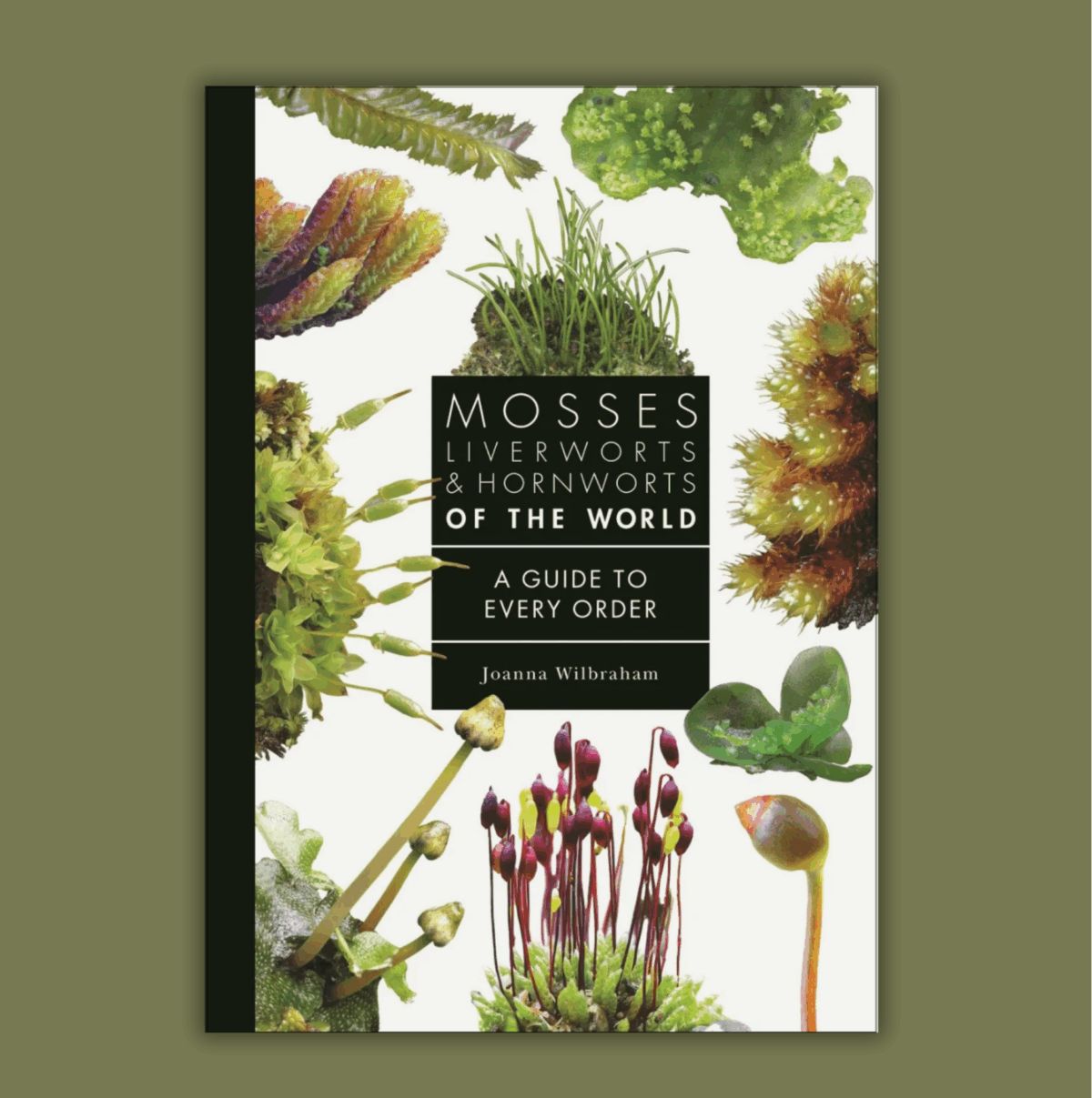

Mosses, Liverworts, and Hornworts of the World makes sense of this highly diverse group of miniature plants, differentiating between the three lineages and delving into their evolution, anatomy, and life cycles. The result is an unprecedented in-depth look at these exquisitely beautiful and often overlooked organisms.

Mosses, Liverworts, and Hornworts of the World makes sense of this highly diverse group of miniature plants, differentiating between the three lineages and delving into their evolution, anatomy, and life cycles. The result is an unprecedented in-depth look at these exquisitely beautiful and often overlooked organisms.

Joanna Wilbraham is an active member of the British Bryological Society and Principal Curator at the Natural History Museum, London, where she leads the curatorial team responsible for the collections of algae, bryophytes, and lichens. At just over two million specimens, this is one of the most significant research collections of its kind in the world.

We recently spoke to Joanna about Mosses, Liverworts, and Hornworts of the World, where she told us how she decided which species to include, threats facing these groups and what projects are on her horizon.

Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about yourself, your background, and how you came to write this book?

I first became interested in bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts) as an undergraduate student. I was keen to do my final research project in botany after an inspiring field trip to the Austrian Alps and was presented with two botanical options: an agricultural research experiment on wheat plants or a project working with bryophytes. Neither option sounded very appealing at the time, but I opted for the bryophytes and have never looked back. Almost immediately I noticed a tiny world I hadn’t previously paid any attention to. I was amazed to discover there was an actual club devoted to the study of these plants! I swiftly joined the British Bryological Society which led to many field excursions getting out and about with experts – undoubtedly the best way to get to get to know bryophytes and learn how to identify them.

I’ve been fortunate to be able to work with my favourite plant groups professionally over the course of my career. As a curator at the Natural History Museum, London, I specialised in cryptogamic botany, that’s those plants and plant-like groups that reproduce by spores rather than seeds. I focused on seaweeds and freshwater algae for many years though bryophytes have always stayed on my agenda. I am currently Curator of Mosses at the Museum, and I have the privilege of curating one of the largest and most significant collections of preserved moss specimens in the world.

When I was invited to write a book in Princeton’s ‘A Guide to Every Family’ series I saw an opportunity to bring the wonderful world of bryophytes to a wider audience and also a chance for me to spend time delving into some fascinating research along the way.

How did you decide which species to include in Mosses, Liverworts & Hornworts of the World?

The premise of books in this series is to provide a complete overview of a group at some appropriate taxonomic level. Classifications are constantly in flux as new research reveals more about the natural world but, at the time of writing the book, bryophytes were classified into 73 accepted taxonomic orders and this looked like a good starting point to base the narrative around. Some of these orders represent huge diverse groupings. For example, the Hypnales are an immense group of creeping mosses with over 4,000 genera, so I squeezed in a few example genus profiles here to showcase their diversity. In contrast, some other orders are only represented by one known extant genus, so for those the decision of what genera to include made itself. Some bryophytes are so charismatic that I simply had to include them, such as Dawsonia, the world’s largest free-standing moss. I did give in to some personal biases to include some of my favourite plants like the beautiful Myurium in the Hypnales. However, all the taxonomic entries had to pull their weight by contributing to the broader narrative of the book, such as revealing something about their evolutionary past, their adaptations to a world in miniature or how they are responding to a rapidly changing planet. Within these parameters, I chose 100 genera to illustrate the structural and evolutionary diversity of bryophytes from around the world.

Can you tell us about the most interesting species that you’ve learned about while researching your book? ?

There are many fascinating species I knew from the outset had to have their stories included. We meet a moss that glows in the dark; mosses that grow on dung and decaying corpses; a moss that could allegedly survive on Mars and a moss that saved the life of a Victorian explorer in western Africa. The structure of the book also forced me to peer around obscure taxonomic corners and investigate species which I hadn’t come across before. I got to know some new plants like the large charismatic tropical moss Sorapilla. This genus is so rare it was only known from a handful of historic herbarium specimens until a student on a botanical fieldtrip in the Queensland rainforest discovered a new population in 2015! It was also fun to discover more stories about people’s interactions with bryophytes. I needed to research the liverwort genus Solenostoma and in particular the species S. vulcanicola which has a remarkable capacity to thrive in acidic hot springs where is forms extensive, lime-green cushions. Known locally in Japan as the ‘Chatsubomi moss’, specialist tours are available to visit this plant on the Chatsubomi tour bus and now I really want to go to Japan!

Given our rapidly changing climate, what are the largest threats facing these groups, and how can we safeguard them going forward?

We are witness to increasing threats to the survival of bryophytes in their natural habitats around the world. Recent studies have reported that around 20% of European bryophyte species are threatened with extinction. These worrying declines result from the combined consequences of climate breakdown and habitat destruction.

The most immediate threat to bryophytes is the destruction and degradation of their natural habitats. Sphagnum mosses, which form peatlands, play an essential role in our planet’s biochemical cycles, sequestering huge quantities of carbon. The extensive peatlands of the boreal north store twice as much carbon as tropical forests. Alarmingly, increasing temperatures are threatening the existence of these peatland bogs as they risk drying out in warmer conditions. It is more imperative than ever that we protect these peat forming Sphagnum bogs and the wealth of biodiversity that they support. Sphagnum bogs should be treasured and certainly not destroyed for peat extraction to support the horticultural industry. Please make sure to buy peat-free at the garden centre and help save Sphagnum bogs by taking away the demand for these products.

Climate breakdown is having a huge impact on bryophytes. The story that resonated the most for me when I researched the book was that of the rare and enigmatic moss Takakia. This genus represents an ancient lineage and evidence suggests that Takakia plants have existed in the form we are familiar with today for at least 165 million years. Populations of Takakia on the Tibetan Plateau actually predate the uprising of the Himalayas! At a cellular level, these plants have had to adapt at phenomenal rates to protect themselves from the extreme increases in UV radiation and freezing conditions that one finds oneself exposed to when lifted up atop the world’s highest mountain range. However, Takakia faces its greatest challenge yet as the planet is now warming at such an unprecedented rate that even Takakia cannot adapt fast enough and the Tibetan populations are recorded to be steadily declining. Ultimately, the planet’s rapidly changing climate and our global ability to reduce carbon emissions going forward is the driving factor that will determine the fate of many bryophytes.

What’s next for you? Are you working on any other projects that we can hear about?

At the Natural History Museum, I’m responsible for curating and managing the moss herbarium which, with over 700,000 specimens, is one of the largest collections of its kind in the world. Herbaria are taxonomically arranged libraries of preserved plant specimens that provide spatial and temporal distribution data for species. New uses for these collections are constantly coming to light, so it’s a really exciting time for us in the curatorial team and we are busy working on some major projects to make these collections and their associated data more accessible for researchers around the world. I am particularly interested in how we can better leverage our bryophyte herbarium data to support biodiversity and conservation research that can lead to a positive impact for bryophytes in the wild.

The good thing about studying bryophytes is you don’t necessarily need to travel far and wide to find some beautiful species and contribute useful insights on their distribution or biology! I’m looking forward to getting back into some local recording when the hoped for autumn rains revitalise the poor drought frazzled bryophytes of South London. With a magnifying glass to hand there can always be something new to discover.

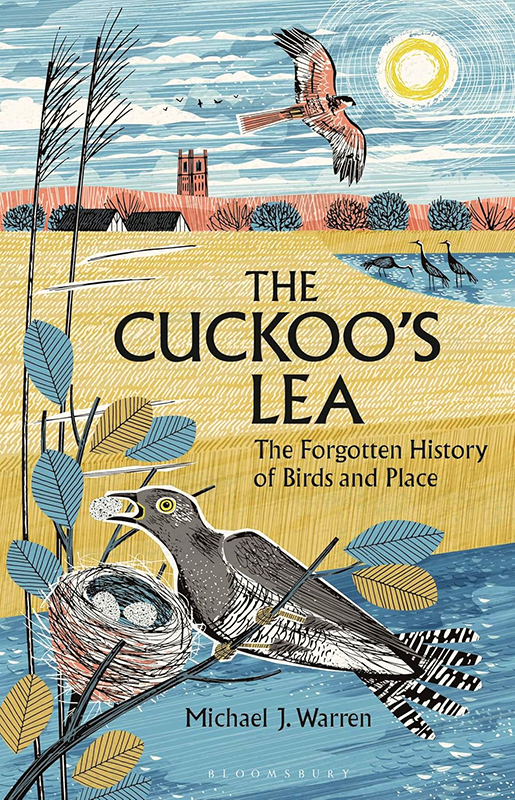

Michael J. Warren is a naturalist and nature writing author who teaches English at a school in Chelmsford. He was an honorary research fellow at Birbeck Colledge, curates The Birds and Place Project, and is a series editor of

Michael J. Warren is a naturalist and nature writing author who teaches English at a school in Chelmsford. He was an honorary research fellow at Birbeck Colledge, curates The Birds and Place Project, and is a series editor of

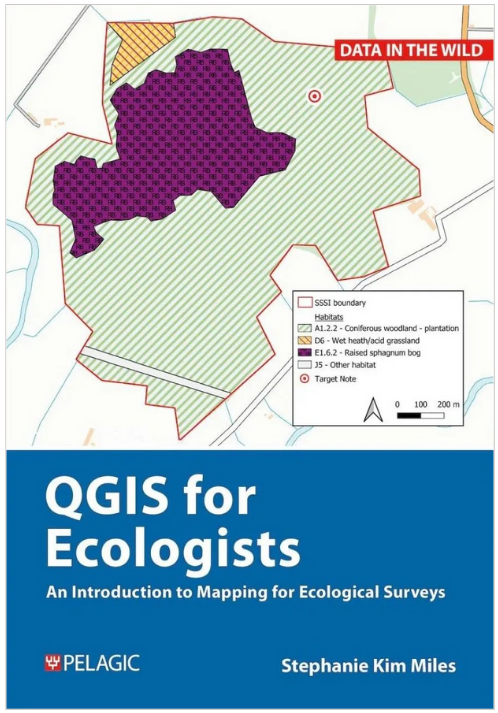

QGIS for Ecologists

QGIS for Ecologists