The NHBS Harp Trap

Earlier this year we were delighted to launch another exciting product manufactured here at our base in Devon. After a concerted period of design and manufacturing effort by our expert Workshop Team, followed by testing and review by ecological professionals, our NHBS Harp Trap was ready for production. The launch of our product into the wildlife equipment market signals the arrival of the only commercially produced harp trap in Europe.

What is a Harp Trap?

A harp trap provides an alternative bat survey method to mist netting or the use of bat detectors. They are particularly useful in situations where bats in flight can be channeled through a natural funnel such as above a water course, a cave or mine entrance or a clear area within a forest.

Harp traps consist of a frame which is either freestanding or suspended, and supports two to four rows of nylon strings. The bats will fly into the nylon strands and then fall unharmed down into a collecting bag below. The catch bag is made from green cotton canvas that is water resistant and breathable and includes heavy duty clear plastic baffles to prevent the bats from escaping. Unlike mist nets, harp traps do not entangle the bats an it has been reported that they can be more effective for surveying bats, potentially capturing higher numbers of individuals.

The NHBS Harp Trap

The new NHBS Harp Trap is a three-bank trap, meaning it has three rows of nylon line. Our trap has a catch area of approximately 4m2 and catch bag which is around 60cm deep. It folds down neatly into a bespoke carry bag and weighs approximately 15kg-full specifications and dimensions are below. The trap takes two people around 10 minutes to assemble and stands on four sturdy, extendable legs and which can be arranged at the height that you need the trap to be. There is also the option to anchor the harp trap with guy ropes in windy conditions. The trap can also be adapted to be suspended if this is required.

Our trap has a few innovative features designed to make assembly and disassembly easier. Firstly the strings are wrapped around a winding mechanism which greatly reduces the stress and time-consuming act of sorting through tangled lines in the dark.

Our trap has a few innovative features designed to make assembly and disassembly easier. Firstly the strings are wrapped around a winding mechanism which greatly reduces the stress and time-consuming act of sorting through tangled lines in the dark.

There is also an extension under the catch bag, which prevents the bats from flying underneath the trap and this doubles as protection for the component parts as it wraps around the disassembled trap when it is stored in its bag.

Dimensions:

Catch area: 4m2 approximately

Catch area L x W: 180 x 225cm

Length: 180cm

Catch bag depth: 60cm

Catch bag width: 44cm

Weight: 15kg

Folded dimensions (in carry bag)

Height: 46cm

Length: 200cm

Width: 22cm

Operational dimensions

With legs fully retracted:

Height 314cm

Width (at base): 62cm

Length (at base): 230cm

With legs fully extended:

Height: 372cm

Width (at base): 100cm

Length (at base): 252cm

Testing

As our harp trap evolved, prototypes were trialed and reviewed by ecology professionals; Professor Fiona Mathews of Sussex University and Neil Middleton of Batability. Their expertise and excellent feedback helped us develop our the harp trap to the point that it was now ready to go live.

The team at NHBS have done an excellent job in coming up with a new and refreshing approach to harp trapping, which shows many innovative and useful design features. When testing the equipment we were able to demonstrate that it was quicker/easier to assemble than competitor’s products. We are happy to recommend this harp trap, and will be ordering one ourselves, to be used during our training courses and for bat-related research.

Neil Middleton, BatAbility Courses & Tuition

The Law

Harp traps can only be sold to those who are licensed to use them. If you hold such a licence, we will ask to see a copy of your NE, NRW or SNH licence when you contact us about your purchase. If you are purchasing from overseas, we will request details about your institution and research.

NHBS Manufacturing

NHBS manufactures marine, freshwater and terrestrial survey tools, all carefully designed to meet the demands of researchers, consultants, public authorities and educators in the environment sector. Made by our team of expert engineers, fabricators and seamstresses, our products have become renowned for their quality, durability and affordability.

Find out more about our manufacturing.

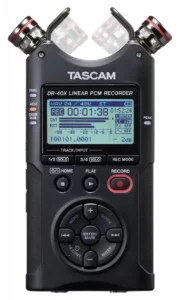

Key accessories for using alongside your harp trap

The Petzl Tikka Headtorch is a high-power and easy to use headtorch that can produce a light beam with a brightness of up to 300 lumens. It is available in four colours and can be powered with either three AAA batteries (included) or using the Petzl CORE rechargeable lithium-ion battery.

The Petzl Tikka Headtorch is a high-power and easy to use headtorch that can produce a light beam with a brightness of up to 300 lumens. It is available in four colours and can be powered with either three AAA batteries (included) or using the Petzl CORE rechargeable lithium-ion battery.

The Kite LED Loupe Triplet Hand Lens 10 x 21 provides crystal clear images which are enhanced with its ring of LED lights. This product may prove invaluable when trying to identify some of the tiny distinguishing features of certain bat species.

The Kite LED Loupe Triplet Hand Lens 10 x 21 provides crystal clear images which are enhanced with its ring of LED lights. This product may prove invaluable when trying to identify some of the tiny distinguishing features of certain bat species.

The A4 Portrait Waterproof Clipboard allows you to write in the field without having to worry about the rain. A waterproof plastic covering system helps to keep your paper dry and can be closed over the clipboard with the strong velcro fastener.

The A4 Portrait Waterproof Clipboard allows you to write in the field without having to worry about the rain. A waterproof plastic covering system helps to keep your paper dry and can be closed over the clipboard with the strong velcro fastener.

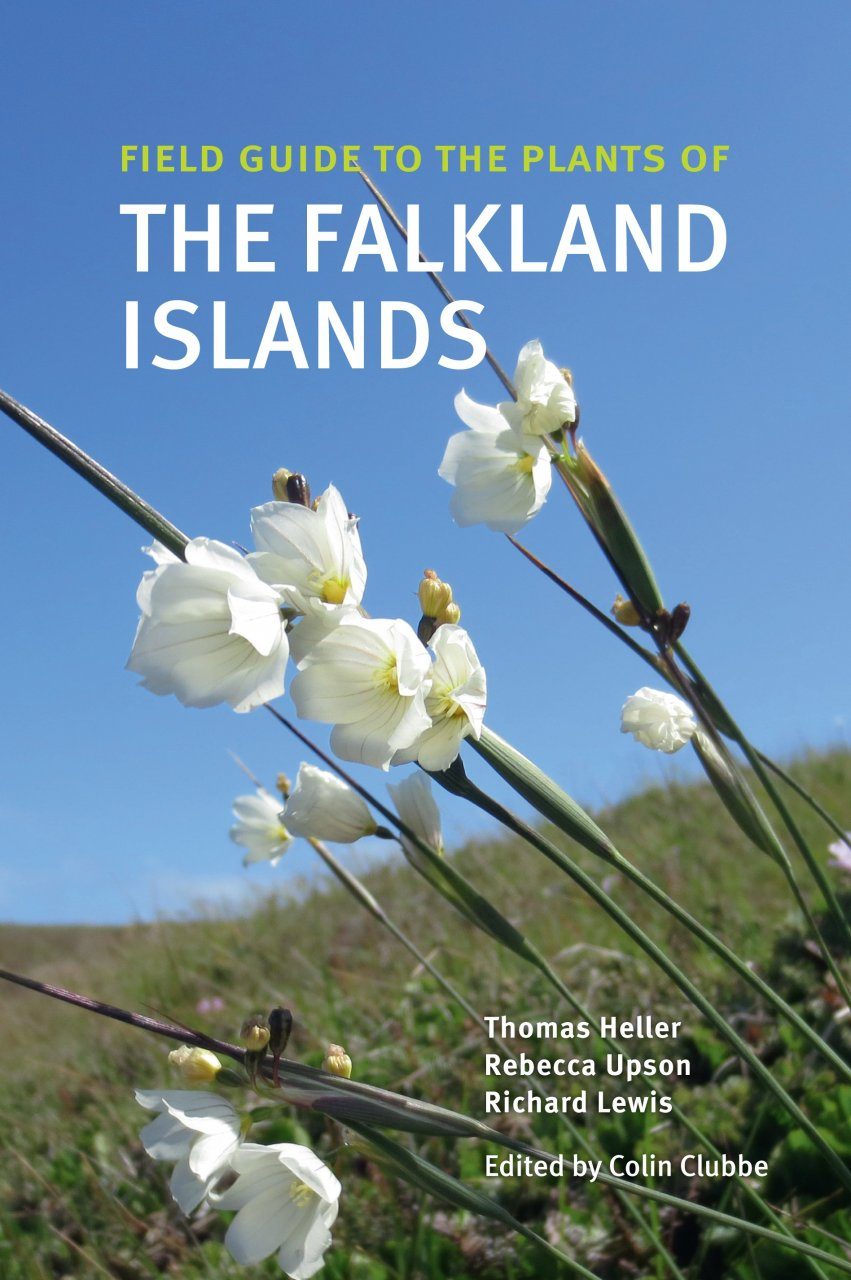

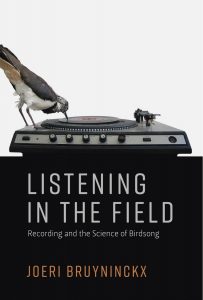

Books

The Bats of Britain and Europe

The Bats of Britain and Europe

Paperback | Sept 2018

Paperback | July 2012

Field Guide to Bats of the Amazon

Field Guide to Bats of the Amazon

Paperback | Feb 2018

The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

despite the brand name this popular

despite the brand name this popular

We asked Simon a few questions about the inspiration behind writing his new book and his hopes and ambitions for the wildlife of Britain.

We asked Simon a few questions about the inspiration behind writing his new book and his hopes and ambitions for the wildlife of Britain. 1. Can you tell us a little about your background and how you got interested in the natural world?

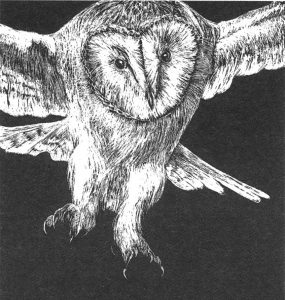

1. Can you tell us a little about your background and how you got interested in the natural world? 4. The Barn Owl is often described in your book; would you say that it was the totem species on the marsh, or would you give that accolade to something else?

4. The Barn Owl is often described in your book; would you say that it was the totem species on the marsh, or would you give that accolade to something else? 7. Do you have any new projects in the pipeline that you’d like to tell us about?

7. Do you have any new projects in the pipeline that you’d like to tell us about?

To get to know Stephen Rutt and his new book, we asked him a few questions on his inspiration, advice and some interesting facts he’s discovered on his journey while writing

To get to know Stephen Rutt and his new book, we asked him a few questions on his inspiration, advice and some interesting facts he’s discovered on his journey while writing

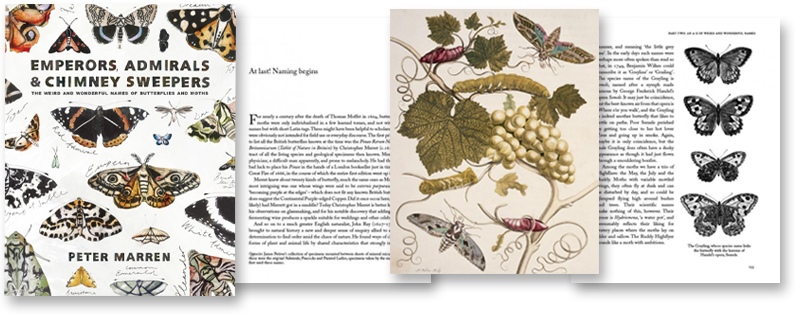

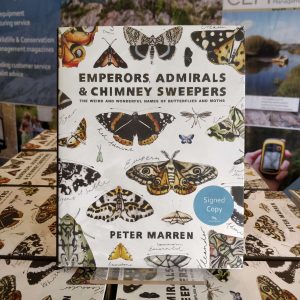

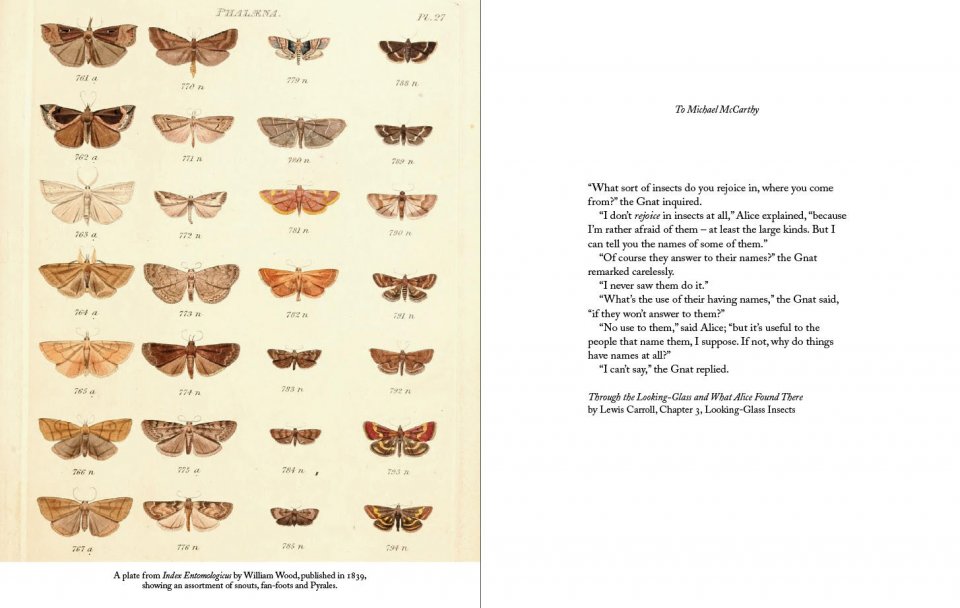

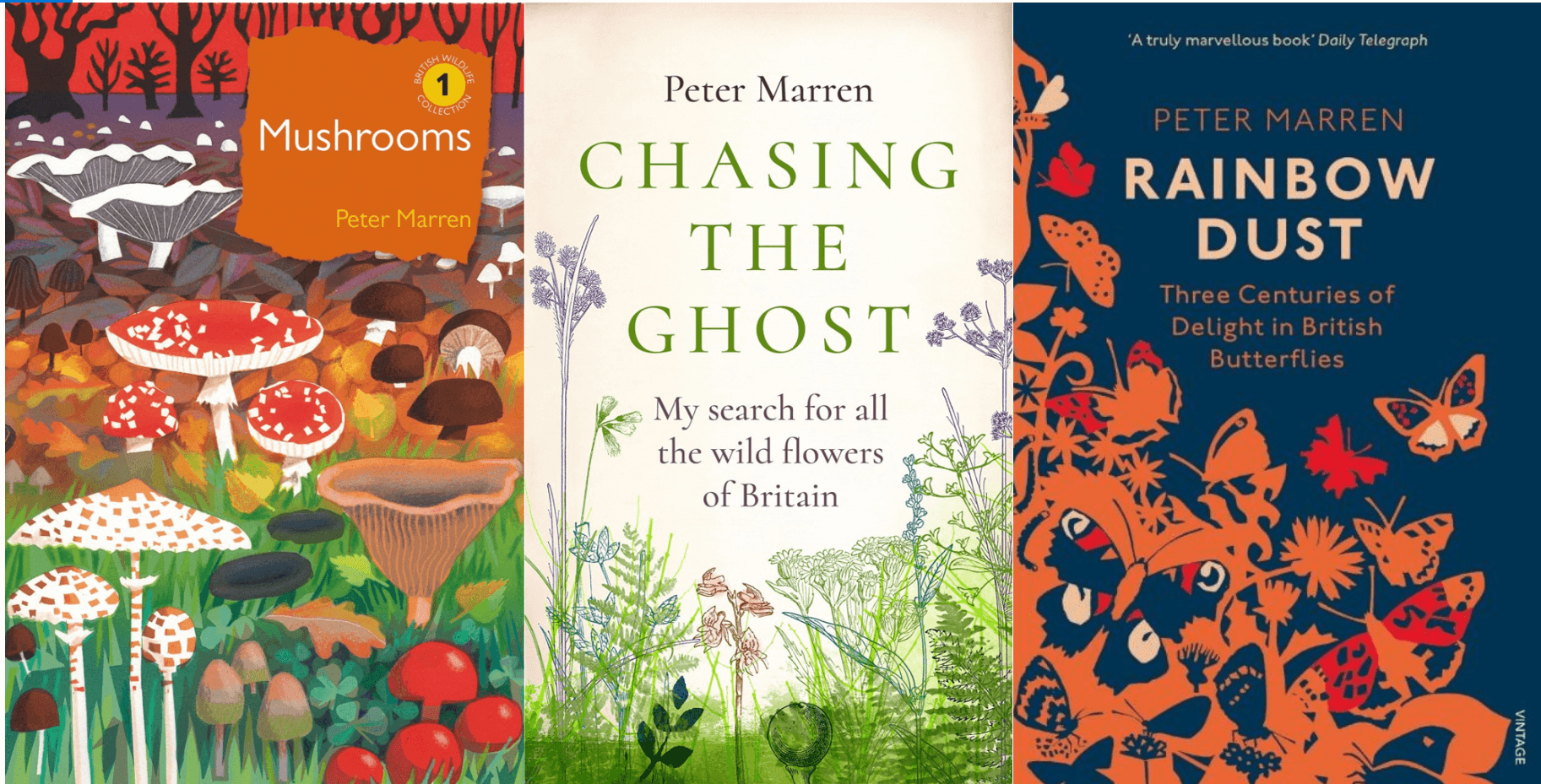

I’m a natural history writer (in the sense that I’ve written a lot about natural history) with a background in nature conservation in Britain. I’ve loved butterflies and moths since boyhood, and I suppose I must have realised even then that many of them have unusual names. What the hell was an eggar? Or a lutestring? Probably like most people I didn’t think too much about it – weren’t names just labels? – until, out of curiosity, I went into the name of the Red Admiral, Vanessa atalanta, and discovered a real Vanessa and a real Atalanta. And then I realised that even Latin names weren’t randomly chosen but had a particular resonance with that particular species. Names hid a whole new world of allusion, poetry and wordplay. I discovered that those who named our Lepidoptera, in English and Latin, were equally educated in the arts and the sciences. They knew their myths, and they knew about colours and designs, and they were completely fascinated. I feel a strange empathy with that vanished world.

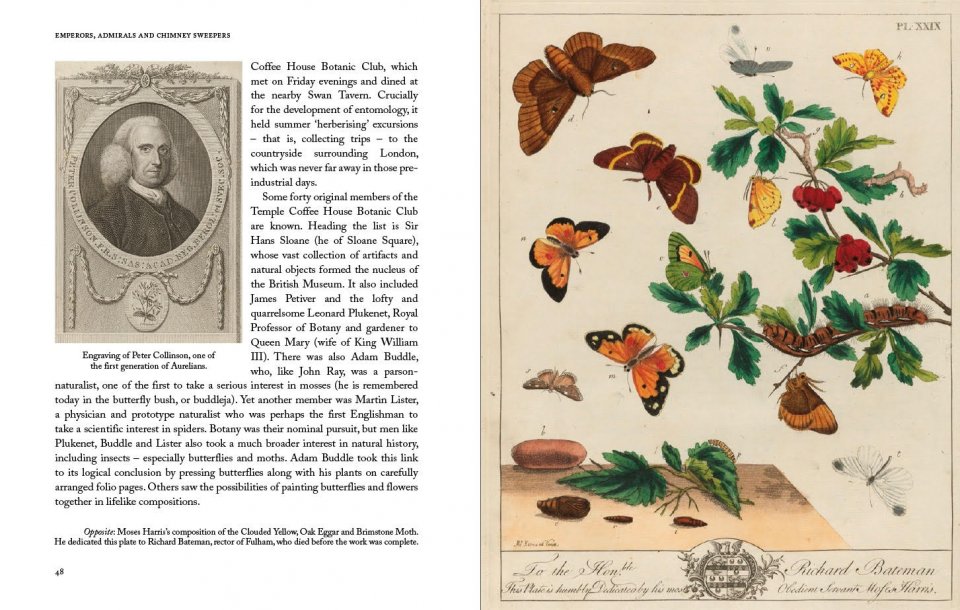

I’m a natural history writer (in the sense that I’ve written a lot about natural history) with a background in nature conservation in Britain. I’ve loved butterflies and moths since boyhood, and I suppose I must have realised even then that many of them have unusual names. What the hell was an eggar? Or a lutestring? Probably like most people I didn’t think too much about it – weren’t names just labels? – until, out of curiosity, I went into the name of the Red Admiral, Vanessa atalanta, and discovered a real Vanessa and a real Atalanta. And then I realised that even Latin names weren’t randomly chosen but had a particular resonance with that particular species. Names hid a whole new world of allusion, poetry and wordplay. I discovered that those who named our Lepidoptera, in English and Latin, were equally educated in the arts and the sciences. They knew their myths, and they knew about colours and designs, and they were completely fascinated. I feel a strange empathy with that vanished world. It started as a kind of sequel to my book Rainbow Dust, about how and why butterflies and moths inspire people. Names were confined to a single chapter in that book, but there was so much more to say, not only about the names themselves but the social ambience that spawned them: the world of Georgian London with its clubs and field excursions, its gorgeous illustrated books and the sense that nature was all the more wonderful for being 1) divinely inspired and 2) almost completely unknown.

It started as a kind of sequel to my book Rainbow Dust, about how and why butterflies and moths inspire people. Names were confined to a single chapter in that book, but there was so much more to say, not only about the names themselves but the social ambience that spawned them: the world of Georgian London with its clubs and field excursions, its gorgeous illustrated books and the sense that nature was all the more wonderful for being 1) divinely inspired and 2) almost completely unknown.

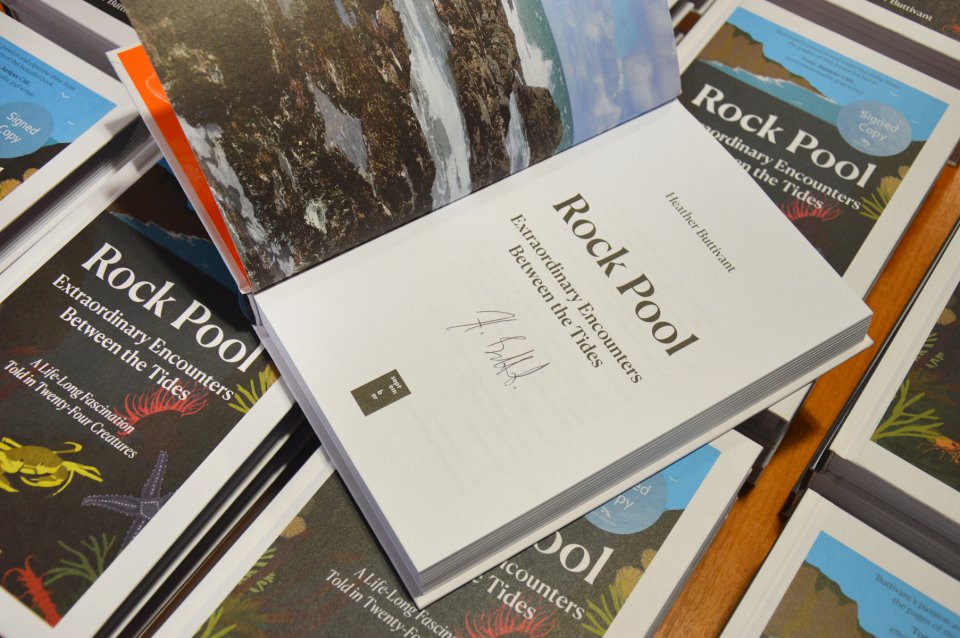

the variety of shapes and textures and the vibrant colours fascinated me. The longer I looked into rock pools, the further I was reeled in. It’s a passion I have no intention of out-growing: no matter how much I know, there is always more to learn.

the variety of shapes and textures and the vibrant colours fascinated me. The longer I looked into rock pools, the further I was reeled in. It’s a passion I have no intention of out-growing: no matter how much I know, there is always more to learn.