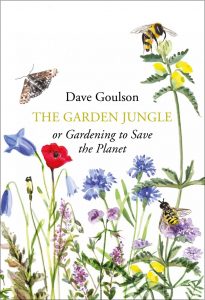

Dave Goulson is a Professor of Biology at the University of Sussex and nature writer, with a particular passion for bees. Bee Quest and A Buzz in the Meadow were bestsellers, and his latest book, The Garden Jungle is all about the wildlife that lives with us: in our gardens and parks, between the gaps in the pavement, and in the soil beneath our feet – an insight into the the wildlife that lives right under our noses.

Dave Goulson is a Professor of Biology at the University of Sussex and nature writer, with a particular passion for bees. Bee Quest and A Buzz in the Meadow were bestsellers, and his latest book, The Garden Jungle is all about the wildlife that lives with us: in our gardens and parks, between the gaps in the pavement, and in the soil beneath our feet – an insight into the the wildlife that lives right under our noses.

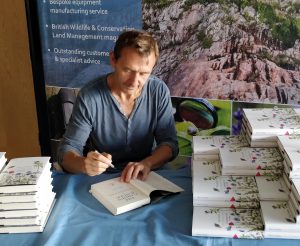

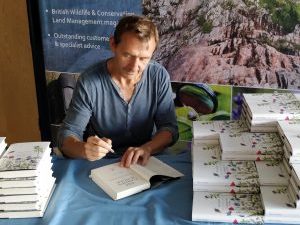

Dave visited NHBS to meet the team and sign a few copies (now sold out) of The Garden Jungle. He also answered a few questions about the inspiration behind his new book and his hopes and ambitions for the gardens of Britain.

- How did your interest in the natural world begin?

I’ve no idea! I have been somewhat obsessed by wildlife, particularly by insects, for as long as I can remember. When I was only five or six years old I remember collecting cinnabar caterpillars from the weeds on the edge of my school playground and rearing them up on my bedroom windowsill in jam jars. I never grew out of my interest, and have been lucky enough to find a way to make a living out of it.

2. Could you tell us a little about the research that went into writing The Garden Jungle?

I’ve been both gardening and studying insects for all of my adult life. The two go hand in hand, for if you grow the right plants, and garden in the right way, you can attract all sorts of insects to your garden. I’ve often done my scientific experiments from home, for example studying bee behaviour and the flowers that they choose. I also try out many of the techniques that are said to help wildlife for myself; my garden is full of more than twenty homemade bee hotels, two ponds, nine compost heaps, four or five log piles, a wildflower meadow area, half a dozen ‘hoverfly lagoons’ and more.

3. What fauna and flora gives you the most pleasure to see in your garden?

It is hard to beat the excitement of seeing the first brimstone butterfly of the year, a flash of bright yellow usually seen on the first warm day in late February or March, a sure sign that spring is coming. But bees are my real obsession, particularly bumblebees, colourful, furry, and endearingly clumsy insects that bring the flower borders to life with their buzzing activity.

4. Are you a keen gardener yourself?

I love gardening. When I’m not at work or asleep, I am somewhere in my two acre garden in the Sussex Weald, growing veg, fruit and flowers, and looking after the birds and the bees. It is my own little piece of heaven.

5. Have there been any changes over the past fifty years – either for the benefit or to the detriment of wildlife in the way people view their gardens?

There has certainly been a great increase in interest in encouraging wildlife into our gardens, for example via bird feeders, tit boxes, bee hotels and by planting bee-friendly flowers. Many of us believe that gardens can be places where people and nature live in harmony. On the other hand there have been many detrimental changes too; Astroturf lawns, decking, hard paving, and a huge increase in the number of chemicals available for use. Gardening has become big business; nowadays many people’s idea of gardening is to drive to some vast garden centre and fill the back of their car with annual bedding plants grown in peat-based composts, drenched in pesticides and sold in disposable plastic pots. There is nothing green about that approach to gardening.

6. If someone wanted to link gardens together for the benefit of wildlife, what would be your advice to enlist the neighbourhood’s cooperation?

Often the best way to convince people to change is to show them the alternative. If your garden is wildlife-friendly, invite your neighbours round for a coffee and show them the butterflies nectaring on flowers, the bees busy stocking their bee hotel, and the flowers in your not-too-tightly-mowed lawn. Offer them some seeds or cuttings of bee-friendly flowers; I give comfrey roots to anyone willing to grow them, it is one of the very best plants for bumblebees and I’m trying to encourage everyone to have a clump of it somewhere.

7. Do you have any new projects in the pipeline that you’d like to tell us about?

With colleagues at Sussex University I recently launched the Buzz Club, a nationwide organisation which is working with the public to do experiments to test interventions for garden wildlife. For example, we are asking people to test out creating a ‘hoverfly lagoon’, miniature ponds intended to provide homes for the offspring of some types of hoverfly. Find out more here: https://www.thebuzzclub.uk/.

Signed copies

A very limited number of The Garden Jungle, signed by Dave Gouslon are available from NHBS. *Signed copies are now sold out*

A very limited number of The Garden Jungle, signed by Dave Gouslon are available from NHBS. *Signed copies are now sold out*

The Garden Jungle

Hardback | July 2019| £14.99 £16.99

The wildlife that lives right under our noses, in our gardens and parks, between the gaps in the pavement, and in the soil beneath our feet.

Discover other titles by Dave Goulson, on special offer until the end of August 2019

Bee Quest

Paperback | April 2018

An endearing account of the search for rare bees. – The Observer £7.99 £9.99

A Buzz in the Meadow

Paperback | April 2015

A fascinating look at the insect world found in one field in France – NHBS

£7.99 £9.99

A Sting in the Tale

Paperback | April 2014

A very readable introduction to the remarkable world of bees and bee conservation. – Good Book Guide

£7.99 £9.99

All prices correct at the time of publication.

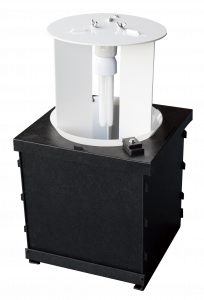

Our trap has a few innovative features designed to make assembly and disassembly easier. Firstly the strings are wrapped around a winding mechanism which greatly reduces the stress and time-consuming act of sorting through tangled lines in the dark.

Our trap has a few innovative features designed to make assembly and disassembly easier. Firstly the strings are wrapped around a winding mechanism which greatly reduces the stress and time-consuming act of sorting through tangled lines in the dark.

The

The  The

The  The

The

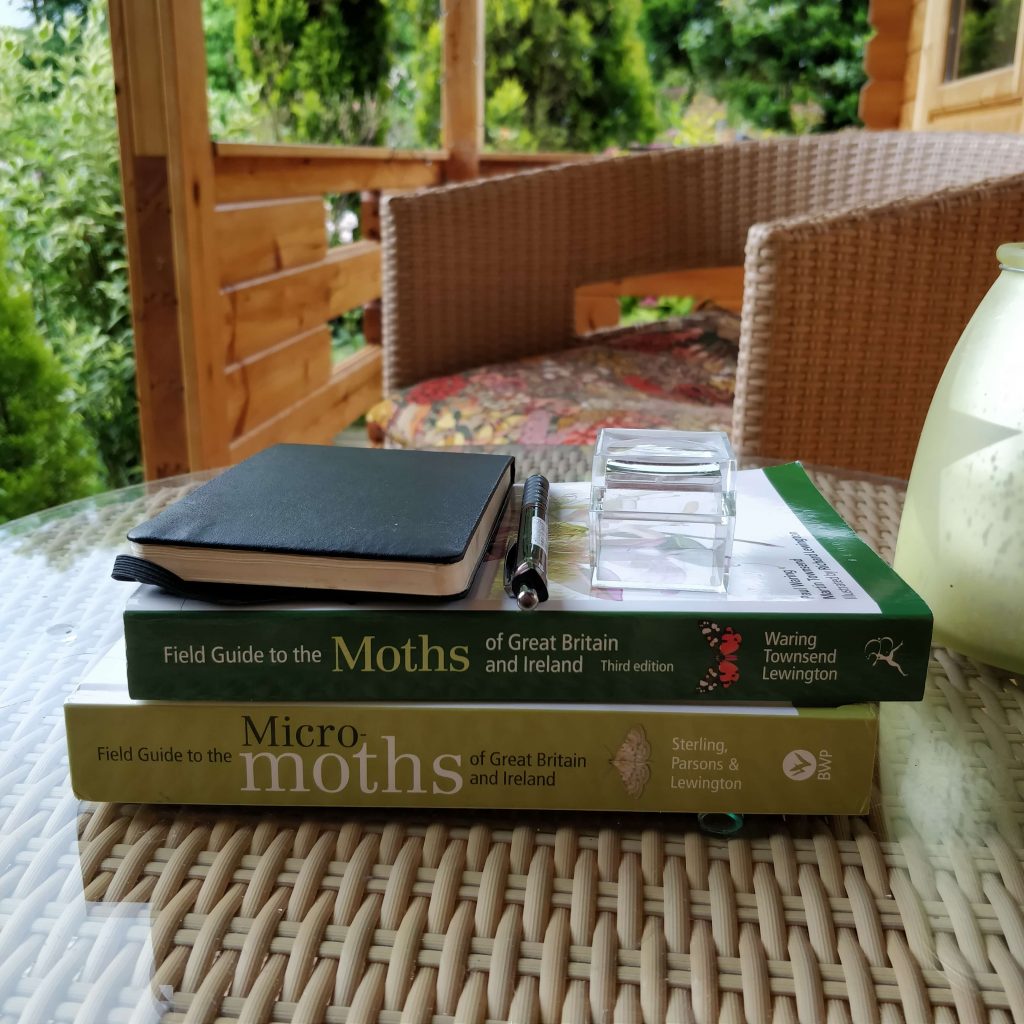

The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

despite the brand name this popular

despite the brand name this popular

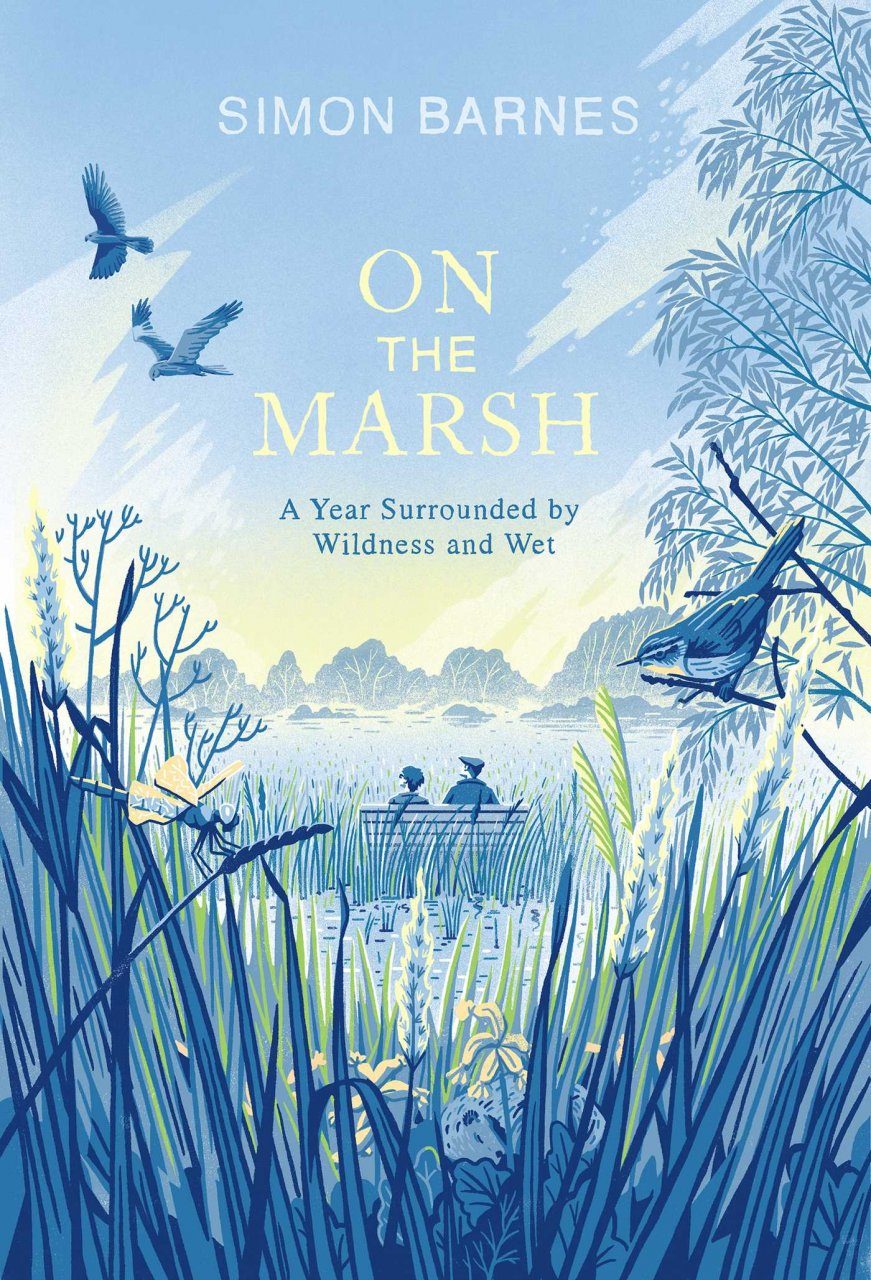

We asked Simon a few questions about the inspiration behind writing his new book and his hopes and ambitions for the wildlife of Britain.

We asked Simon a few questions about the inspiration behind writing his new book and his hopes and ambitions for the wildlife of Britain. 1. Can you tell us a little about your background and how you got interested in the natural world?

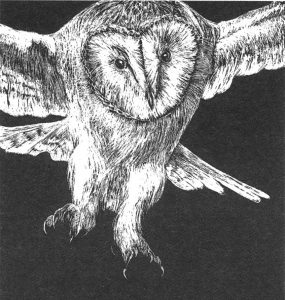

1. Can you tell us a little about your background and how you got interested in the natural world? 4. The Barn Owl is often described in your book; would you say that it was the totem species on the marsh, or would you give that accolade to something else?

4. The Barn Owl is often described in your book; would you say that it was the totem species on the marsh, or would you give that accolade to something else? 7. Do you have any new projects in the pipeline that you’d like to tell us about?

7. Do you have any new projects in the pipeline that you’d like to tell us about?

To get to know Stephen Rutt and his new book, we asked him a few questions on his inspiration, advice and some interesting facts he’s discovered on his journey while writing

To get to know Stephen Rutt and his new book, we asked him a few questions on his inspiration, advice and some interesting facts he’s discovered on his journey while writing