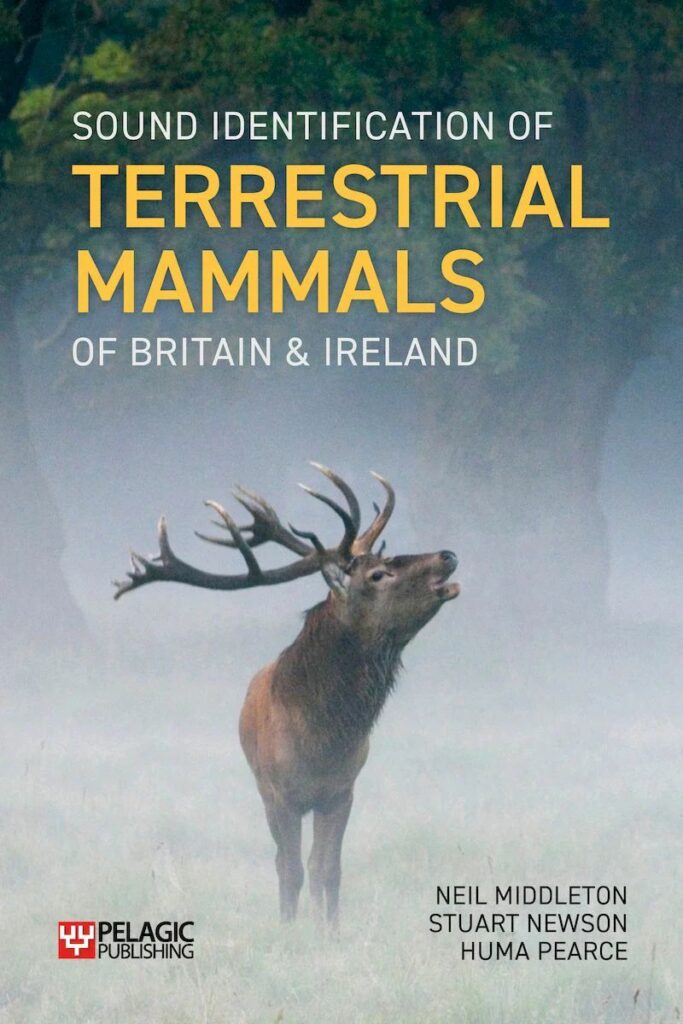

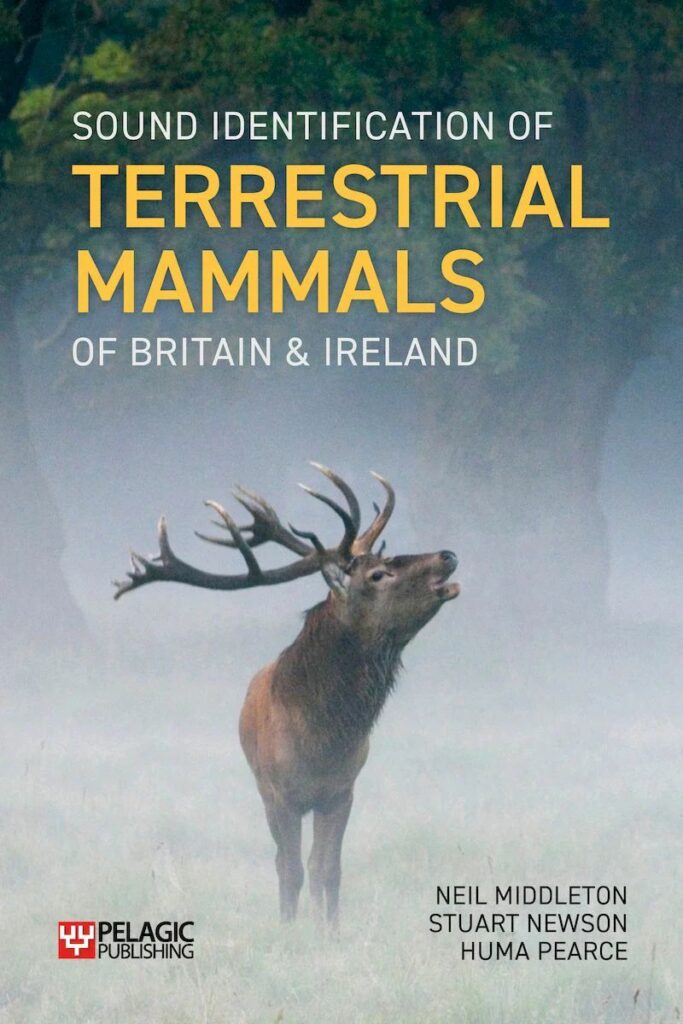

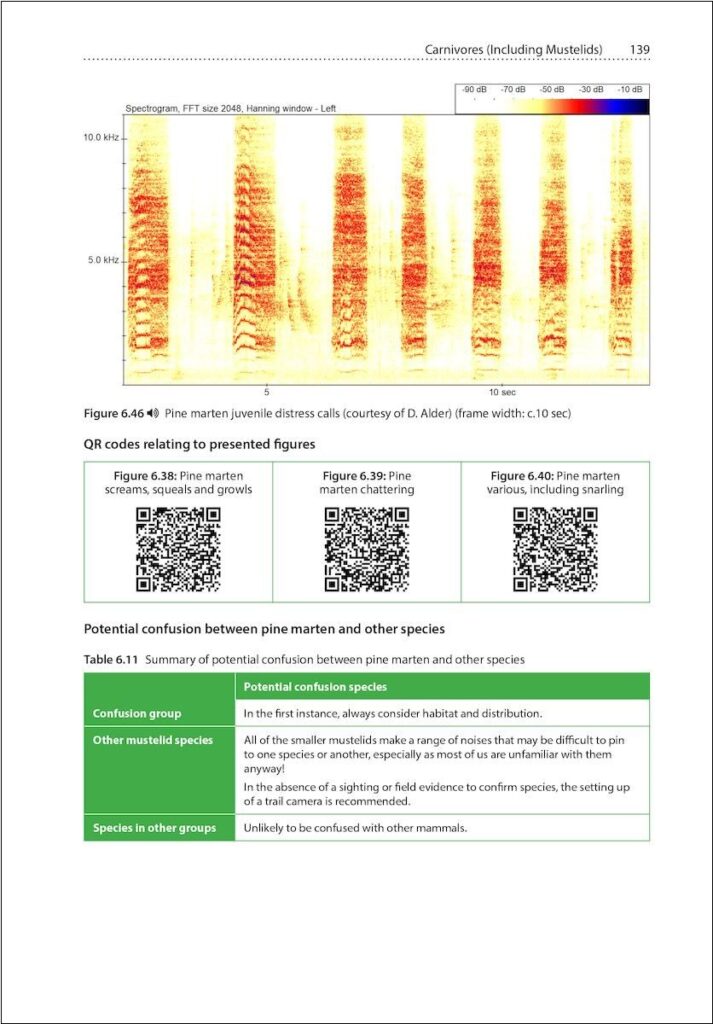

This groundbreaking book provides the reader with a unique and practical guide to collecting and using acoustic survey data to identify terrestrial mammals. Covering 42 species that can be found in Britain and Ireland, the text includes guidance on survey methods, analysis of sound recordings and details of appropriate software. As well as containing specific spectrogram examples for each species, the book allows the reader access to a downloadable sound library containing more than 250 recordings.

This groundbreaking book provides the reader with a unique and practical guide to collecting and using acoustic survey data to identify terrestrial mammals. Covering 42 species that can be found in Britain and Ireland, the text includes guidance on survey methods, analysis of sound recordings and details of appropriate software. As well as containing specific spectrogram examples for each species, the book allows the reader access to a downloadable sound library containing more than 250 recordings.

Neil Middleton is a licensed bat worker and trainer and is the owner of BatAbility Courses & Tuition, an organisation that delivers ecology-related skills development to customers throughout the UK and beyond. He has studied bats for over 25 years, with a particular focus on their acoustic behaviour (echolocation and social calls) and is the author of Social Calls of the Bats of Britain and Ireland, Is That a Bat?, and The Effective Ecologist.

Neil Middleton is a licensed bat worker and trainer and is the owner of BatAbility Courses & Tuition, an organisation that delivers ecology-related skills development to customers throughout the UK and beyond. He has studied bats for over 25 years, with a particular focus on their acoustic behaviour (echolocation and social calls) and is the author of Social Calls of the Bats of Britain and Ireland, Is That a Bat?, and The Effective Ecologist.

Stuart Newson is a Senior Research Ecologist at the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), where he is involved in survey design and data analysis from national citizen-science surveys. Stuart’s work on bioacoustics has included creating tools to identify European bats, bush-crickets and small mammal species from their ‘calls’. This resulted in the BTO Acoustic Pipeline, which integrates online tools for coordinating fieldworkers, processing recordings, and returning feedback.

Stuart Newson is a Senior Research Ecologist at the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), where he is involved in survey design and data analysis from national citizen-science surveys. Stuart’s work on bioacoustics has included creating tools to identify European bats, bush-crickets and small mammal species from their ‘calls’. This resulted in the BTO Acoustic Pipeline, which integrates online tools for coordinating fieldworkers, processing recordings, and returning feedback.

Neil and Stuart recently took some time out of their busy schedules to answer some of our questions about their most recent book. In this Q&A we discuss the challenges involved in acoustic monitoring of mammals, the author’s hopes for the future of this area of study, and much more.

You each have a passion for acoustic monitoring – how did you come to be working together on this project?

Before we first met, Stuart was becoming interested in what else is recorded as ‘by-catch’ when you leave out a static bat detector to record bats. He had previously become interested in the sound identification of bush-crickets which are commonly recorded during bat surveys in southern Britain, and thanks to work that Neil was involved with (e.g. the first edition of the book The Social Calls of the Bats of Britain & Ireland), Stuart was becoming increasingly interested in bat social calls. At this time, he realised that small mammals are also quite commonly recorded as ‘by-catch’ during bat surveys, and was starting to appreciate that unless you had a good understanding of bat echolocation and social calls, there was scope for mis-identifying small mammals calls as being produced by bats.

When Neil started working on the book, Is That a Bat? A Guide to Non-Bat Sounds Encountered During Bat Surveys (ITAB), Stuart had already made available some online resources to help bat workers identify bush-crickets, which were able to feed into Neil’s book, and he also had some first recordings of some small mammal recordings that he was able to contribute to ITAB, which were very useful additions to the recordings that Neil had been gathering independently.

At about the same time, Stuart had met Huma Pearce, the third author on this book, and had started to work with her on an ‘edge-of-desk’ project to try and collect sound recordings for every species of small mammal in the UK. The aim was to try and collect many hundreds (ideally thousands) of sound recordings of every small mammal species in Britain and Ireland, which we wanted to build into bat classifiers to be able to assist with automatically identifying small mammals (as well as bush-crickets), when these are recorded as by-catch during bat surveys.

Working with Huma, and then Neil, to collect recordings for small mammals to feed into ITAB, and for Stuart to feed into his classifiers, we were now collecting a lot of recordings of small mammal species. After the publication of ITAB, we had learnt a lot more between us, so we wrote a more detailed guide to the sound identification of small mammals in Britain and Ireland, which was published in British Wildlife. After being approached by Pelagic Publishing, Neil was asked if he could author a book covering all terrestrial mammals in our part of the world. This was a much wider group than the one we had worked on up until that point. Neil agreed to the book idea, but only on the basis that Stuart and Huma would be involved as well. Thankfully both Stuart and Huma were ‘up for it’ and between us we managed to produce the book. I think we would all agree that if any one of us had not been involved, the job would’ve been considerably harder and taken much longer.

There currently exists a huge sound library of vocalisations of bats and cetaceans and their use in monitoring these species is now mainstream. Why do you think that this approach has not, so far, been used for other mammals such as those covered in your book?

There currently exists a huge sound library of vocalisations of bats and cetaceans and their use in monitoring these species is now mainstream. Why do you think that this approach has not, so far, been used for other mammals such as those covered in your book?

We think that the main reason that so little has been done on the sound identification of terrestrial mammals (other than bats), is that for small mammals the call rate is quite low compared with other groups such as bats, and because the vocalisations can look like bat calls. I think until our various pieces of work, they have been largely overlooked. Until relatively recently, bat social calls had also been largely ignored by many bat workers, so there were few possibilities for noticing or identifying small mammal calls via that group. For audible mammal species, such as deer, there are alternative survey methods, such as visual surveys, and combined with this the call rate is again quite low, so without tools to help find these calls within large acoustic datasets it has been challenging to find and identify vocalisations by these species. In addition, before this book there was no resource or reference that people could use to help support the sound identification of audible mammals across the full range of species.

Added to this, we feel that the subject is difficult for many people in the non-bat mammal world to engage with and/or know where to start. Hopefully this book will open people’s eyes (and ears!) to the subject, thus meaning that more people will pay more attention to acoustic identification of these species, which will also mean that, overall, our rate of learning as a community will increase substantially as we begin to find out even more about the subject, including of course things that we didn’t appreciate at time of writing.

As well as providing the information and data required for species identification, do you think that acoustic data have the potential to tell us more about species behaviour, social interactions and population dynamics?

We think that there is huge potential for acoustic data to tell us much more about species behaviour, social interactions and population dynamics. As explored in the book, for some species we are able to relate particular call types to behaviour or status, but we still have a lot to learn for many of the species that are included in the book, in order to be able to understand in what situations particular calls are produced. By writing this book, we hope that this will inspire others to build on our work, and to accelerate an improvement in knowledge.

Which of the British terrestrial mammal species have you found the most challenging to study and why?

Which of the British terrestrial mammal species have you found the most challenging to study and why?

It is difficult to give a single answer to this one, but despite each of us having separate thoughts we would all agree on the following.

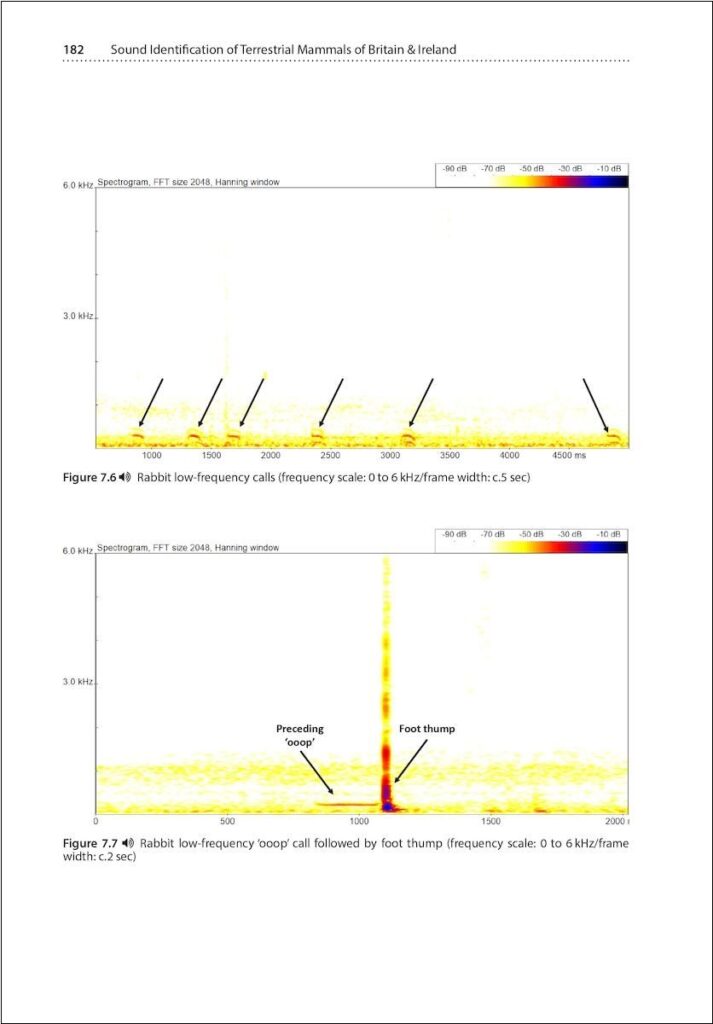

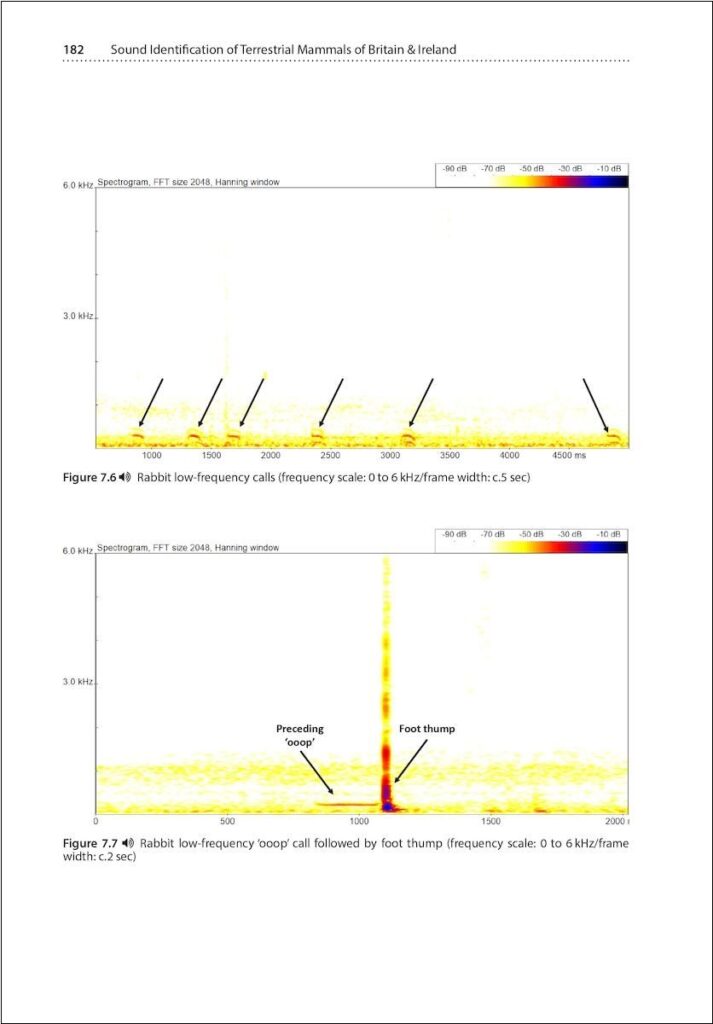

It was extremely difficult to collect or find existing sound recordings of rabbits and hares, because the call rate is extremely low. Huma (assisted by others) put lots of effort into rabbits, but sadly the results were zero. Separately Stuart tried to collect recordings of moles, by sinking microphones into the ground along mole tunnels, but he had no luck despite several weeks of effort.

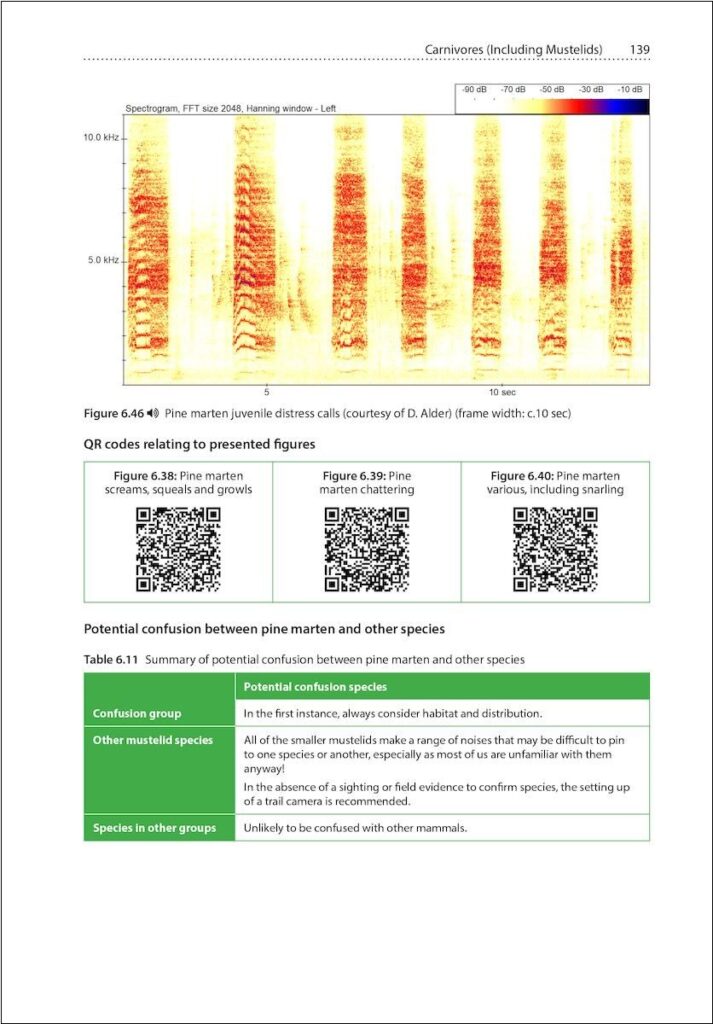

Stuart would like to do more work on the sound identification of mustelids, which we feel we do not understand as much as we would like. We would all like to continue with more work on the small mammals, although we would each have different priorities in that respect. Shrews are of particular interest to us all, and Stuart in particular would definitely like to try and collect more sound recordings of Water Shrews.

Researchers have previously observed regional differences in the vocalisations of small birds recorded in various locations around Britain. Did you notice any geographic variations in the sounds produced by the mammal species you studied?

Personally, we haven’t seen much, if any, evidence of geographic variation in the recordings that we have looked at, but there could very well be regional differences. For some species it can be shown that differences occur at the individual level. This being the case, you could perhaps expect to see differences between social groups and, as such, regional and national differences too. At this point in time the amount of data we have is too small and hasn’t been collected with this in mind, and therefore we haven’t gone looking for an answer to this question ourselves.

There are currently several citizen science projects around the UK that the public can submit sightings to (such as those organised by the Mammal Society or apps such as iRecord). Is there currently anywhere that people can submit records resulting from acoustic data? Or somewhere they can submit their recordings in the hopes of building a library of sound files for each species as there is for bats?

There are currently several citizen science projects around the UK that the public can submit sightings to (such as those organised by the Mammal Society or apps such as iRecord). Is there currently anywhere that people can submit records resulting from acoustic data? Or somewhere they can submit their recordings in the hopes of building a library of sound files for each species as there is for bats?

Not that we are aware of, in the style that you have suggested by your question. However, if someone has heard (not seen) a species and they are happy that it is a diagnostic record for that species in a particular area, we would see no reason why a citizen science project would not accept the ‘sound’ as a valid record of the species being present at that location at that point in time. The key to this, however, is being confident that what was heard couldn’t be a similar noise made by something completely different – so we urge caution. It should also be remembered that in some cases sound identification may actually be more reliable than a visual record of a distant mammal, or a small mammal irrespective of how close it may be to the observer.

In a slightly different direction to your question, Stuart is best placed to talk about the use of such calls in building classifiers. His main interest in mammals has been to build a large sound library of known species recordings that can be used to build classifiers that can help identify the calls of different species automatically within recordings, with the book being secondary or a by-product of this. He believes that having such tools is essential for helping to find the calls of terrestrial mammals in large acoustic datasets, particularly for species where the call rate is low. The sound identification of all species of small mammals included in the book has been built into the ‘bat’ classifiers that comprise the BTO Acoustic Pipeline. The Acoustic Pipeline also includes specific classifiers for some audible species, including the Edible Dormouse. To the best of Stuart’s knowledge this is the first attempt from anywhere in the world to build classifiers for the sound identification of a complete assemblage of small mammals.

What are the next steps required to progress this research and what are your hopes for the future of this field of study?

There is still a lot to learn about the sound identification of mammals in Britain and Ireland, but there are some species groups on which we know we have done much less work and have less understanding than others. In particular, we think that acoustics could be useful for detecting the presence of mustelids (as we have already demonstrated for mice, rats, voles, shrews and dormice), but we would need to try and collect many hundreds (ideally thousands) of known species recordings, to be able to understand the full range of calls that a species can produce. This information could then also be used to create automated classifiers, thus enabling the possibility of efficient detection of species in this group from within large datasets.

As a longer-term ambition, Stuart is keen to work further on the wider sound identification of European mammals, and to extend the geographic and taxonomic scope of the BTO Acoustic Pipeline. Currently, he is able to identify small mammals in bat recordings from elsewhere in Europe at least to genus, by including similar closely related species from the UK in regional classifiers for other parts of Europe. However, he needs more targeted recording of known species to be carried out in order to be able to assign these identifications to species, and to be able to build classifiers that support the sound identification of mammals more widely across Europe.

Our hopes are that this book inspires others in Europe (and further afield) to work on the sound identification of mammals, and more widely to see the opportunities that understanding acoustics can offer.

Sound Identification of Terrestrial Mammals of Britain & Ireland is published by Pelagic Publishing and is available at nhbs.com.

This groundbreaking book provides the reader with a unique and practical guide to collecting and using acoustic survey data to identify terrestrial mammals. Covering 42 species that can be found in Britain and Ireland, the text includes guidance on survey methods, analysis of sound recordings and details of appropriate software. As well as containing specific spectrogram examples for each species, the book allows the reader access to a downloadable sound library containing more than 250 recordings.

This groundbreaking book provides the reader with a unique and practical guide to collecting and using acoustic survey data to identify terrestrial mammals. Covering 42 species that can be found in Britain and Ireland, the text includes guidance on survey methods, analysis of sound recordings and details of appropriate software. As well as containing specific spectrogram examples for each species, the book allows the reader access to a downloadable sound library containing more than 250 recordings. Stuart Newson is a Senior Research Ecologist at the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), where he is involved in survey design and data analysis from national citizen-science surveys. Stuart’s work on bioacoustics has included creating tools to identify European bats, bush-crickets and small mammal species from their ‘calls’. This resulted in the

Stuart Newson is a Senior Research Ecologist at the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), where he is involved in survey design and data analysis from national citizen-science surveys. Stuart’s work on bioacoustics has included creating tools to identify European bats, bush-crickets and small mammal species from their ‘calls’. This resulted in the  There currently exists a huge sound library of vocalisations of bats and cetaceans and their use in monitoring these species is now mainstream. Why do you think that this approach has not, so far, been used for other mammals such as those covered in your book?

There currently exists a huge sound library of vocalisations of bats and cetaceans and their use in monitoring these species is now mainstream. Why do you think that this approach has not, so far, been used for other mammals such as those covered in your book? Which of the British terrestrial mammal species have you found the most challenging to study and why?

Which of the British terrestrial mammal species have you found the most challenging to study and why? There are currently several citizen science projects around the UK that the public can submit sightings to (such as those organised by the Mammal Society or apps such as iRecord). Is there currently anywhere that people can submit records resulting from acoustic data? Or somewhere they can submit their recordings in the hopes of building a library of sound files for each species as there is for bats?

There are currently several citizen science projects around the UK that the public can submit sightings to (such as those organised by the Mammal Society or apps such as iRecord). Is there currently anywhere that people can submit records resulting from acoustic data? Or somewhere they can submit their recordings in the hopes of building a library of sound files for each species as there is for bats?

What inspired you to write a book about the Eurasian Hoopoe?

What inspired you to write a book about the Eurasian Hoopoe?

The Seal Project is an environmental conservation charity based in Brixham, Devon, which

The Seal Project is an environmental conservation charity based in Brixham, Devon, which

‘Easter Bunny’ is one of my favourite seals and can still be seen today resting around the local area. We first encountered him in 2020 as a juvenile seal entangled in industrial strength plastic. He vanished and we feared the worst, however a week later, on Easter Sunday, he was back in the same haul out spot on a girder in the marina, freed from the plastic. At the time of our first sighting, he appeared to have a bunny shape on his right-hand side (alongside a letter ‘A’), but this time the bunny seems to have disappeared with the ‘A’ is clearly visible. He reappeared regularly over the coming years, often seen for a few days and until the last several months always in the same spot, before disappearing for a few days and coming back again. We have seen him elsewhere a number of times, and last winter he was seen socialising with two ‘tagged’ seals (former rescued seals with plastic rear flipper tags for identification), so we look forward to seeing if they return to the area soon too.

‘Easter Bunny’ is one of my favourite seals and can still be seen today resting around the local area. We first encountered him in 2020 as a juvenile seal entangled in industrial strength plastic. He vanished and we feared the worst, however a week later, on Easter Sunday, he was back in the same haul out spot on a girder in the marina, freed from the plastic. At the time of our first sighting, he appeared to have a bunny shape on his right-hand side (alongside a letter ‘A’), but this time the bunny seems to have disappeared with the ‘A’ is clearly visible. He reappeared regularly over the coming years, often seen for a few days and until the last several months always in the same spot, before disappearing for a few days and coming back again. We have seen him elsewhere a number of times, and last winter he was seen socialising with two ‘tagged’ seals (former rescued seals with plastic rear flipper tags for identification), so we look forward to seeing if they return to the area soon too.