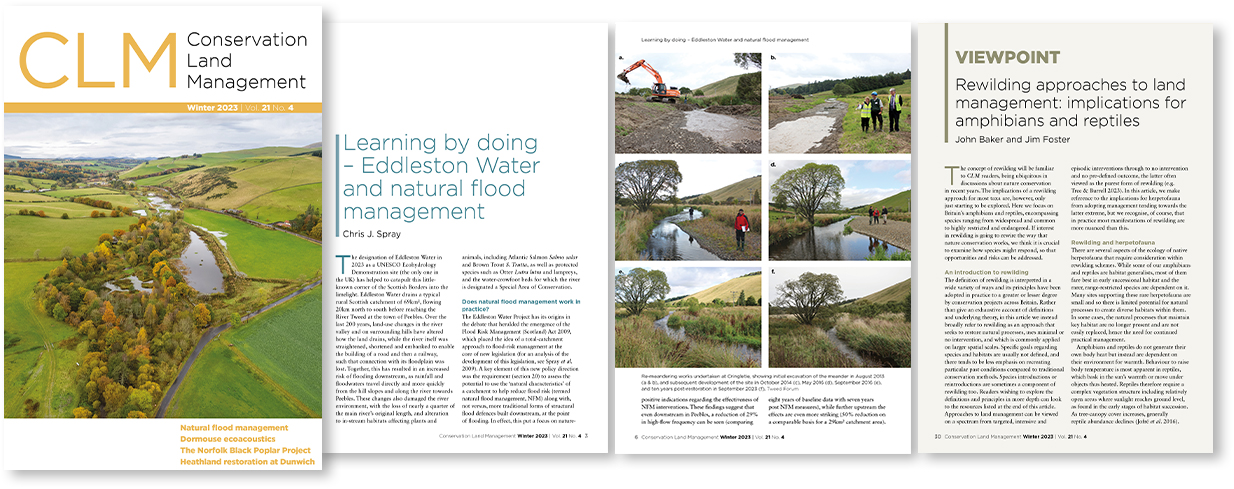

The Winter issue of Conservation Land Management (CLM), out soon, marks the end of volume 21. This issue covers a breadth of topics, including a discussion on the implications of rewilding on Britain’s native herpetofauna, the restoration of heathland on former conifer plantation sites, the native Black Poplar in Norfolk, the exciting potential of ecoacoustic monitoring for Hazel Dormouse surveys and the impressive Eddleston Water Project in Scotland. Read a more detailed summary of the articles featured in this issue below.

Eddleston Water is a tributary of the River Tweed, joining at the Scottish town of Peebles and draining a catchment of 69km². Over the last 200 years, land-use changes in the river valley have altered how the land drains and the river itself has been straightened to allow for the construction of a road and railway. As a result, the connection between the river and its floodplain has been severed, resulting in an increased risk of flooding downstream towards Peebles and changes to in-stream habitats important for wildlife such as Atlantic Salmon, Otter and lampreys. The Eddleston Water Project was set up in 2009 with the aim of reducing the flood risk to downstream communities and improving riparian habitats while maintaining local farm businesses. Interestingly, hydrological and ecological monitoring began two years before natural flood management (NFM) measures were first implemented, and so the Eddleston Water Project has provided, and continues to provide, empirical evidence for the effectiveness of NFM. Professor Chris Spray, the Tweed Forum’s Science Manager for the Eddleston Water Project, describes the NFM interventions that have been used, such as riparian tree planting, re-meandering the straightened channel, the creation of flood-storage ponds and the placement of high-flow restrictor log structures, and the benefits that these have provided across the Eddleston catchment.

Ecoacoustic monitoring, the use of sound to determine a species’ presence or absence, has grown in popularity, but ecoacoustic studies have generally focused on ‘noisier’ animals, such as birds and bats. If this approach could offer a viable alternative to traditional monitoring methods for other species, it could provide a useful tool for ecologists and conservationists while also being less invasive for the animals themselves. A previous article in British Wildlife magazine demonstrated that the vocalisations of small terrestrial mammals (rodents and shrews) could be readily assigned to species with careful examination of recordings and spectrograms, suggesting that ecoacoustics could offer a new means of monitoring these animals. In this article, Jonathan Down, Stuart Newson and Alex Bush look specifically at the potential of acoustic methods in surveys of the Hazel Dormouse, a protected species that has experienced significant declines in the UK. The authors conducted a field test in south Cumbria in two areas where Hazel Dormice had recently been reintroduced in order to investigate how effective two different types of acoustic recorders, AudioMoth (a low-cost option) and the Song Meter Mini Bat Detector, were in detecting the presence of dormice. Here they describe their findings and highlight both the limitations and promise of ecoacoustics for dormouse surveys.

The native Black Poplar is the rarest hardwood tree in Britain – approximately only 7,000 trees remain in Britain. Unfortunately, the population is also heavily male-biased; in the Victorian era many female trees were felled due to the fluffy white seeds that they produce, which were considered unsightly. This and the isolated nature of the remaining trees means that sexual reproduction is essentially non-existent in the wild and many individuals are genetic clones of a small number of trees. Due to their rarity, native Black Poplars have been well recorded in most parts of the country, but in Norfolk records have not been updated since a 2007 census survey. To address this, the Otter Trust launched the Norfolk Black Poplar Project to formulate an accurate and up-to-date picture of the status of the Black Poplar in the county The locations of individual trees recorded in previous surveys were updated and mapped, and cuttings were taken from each tree for genetic testing and propagation. Genetic analysis has allowed each tree’s clonal type and sex to be identified, and here Ben Grief outlines the results from this work and discusses the potential to expand the Black Poplar population in Norfolk.

The Sandlings Heaths in Suffolk, once a vast unbroken landscape, have undergone significant landscape-scale changes in the last century. The planting of coniferous plantations played a part in this, but in 2006 the RSPB entered an agreement with the Forestry Commission to manage areas of clearfell in Dunwich Forest with the aim of restoring heathland and acid grassland habitats of high conservation value (compared to the scrub and trees likely to develop in the absence of management). Here, the authors focus on three cleared areas, describing the management that has been carried out since 2008 to restore the sites to high-quality heathland and what extensive vegetation monitoring has shown regarding the habitats that have since developed.

In Viewpoint, the final article in this issue, John Baker and Jim Foster from the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust discuss the implications of rewilding for Britain’s reptiles and amphibians. The authors broadly refer to rewilding as an approach that aims to restore natural processes with minimal or no intervention, generally applied over larger spatial scales, and highlight why, particularly for our specialist and rare species, rewilding in this sense may not always be the most suitable approach.

In this and every issue you can expect to see Briefing, keeping you up to date with the latest training courses, events and publications, and On the ground, which provides helpful tips and updates on products relevant to land management. Other features, such as Review, which can include letters from readers or updates from our authors, also regularly appear in CLM.

CLM is published four times a year, in March, June, September and December, and is available by subscription only. Subscriptions start from £22 per year. If you would like to read any of these articles, contact info@britishwildlife.com to pre-order a copy and receive the Winter 2023 issue when it is published, in mid-December.

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153).

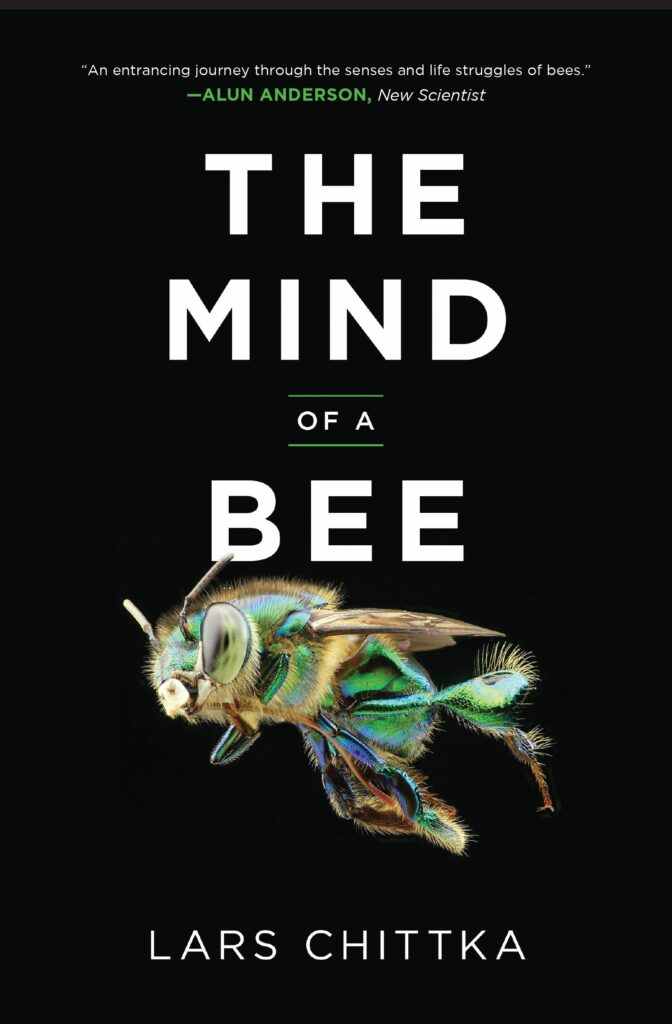

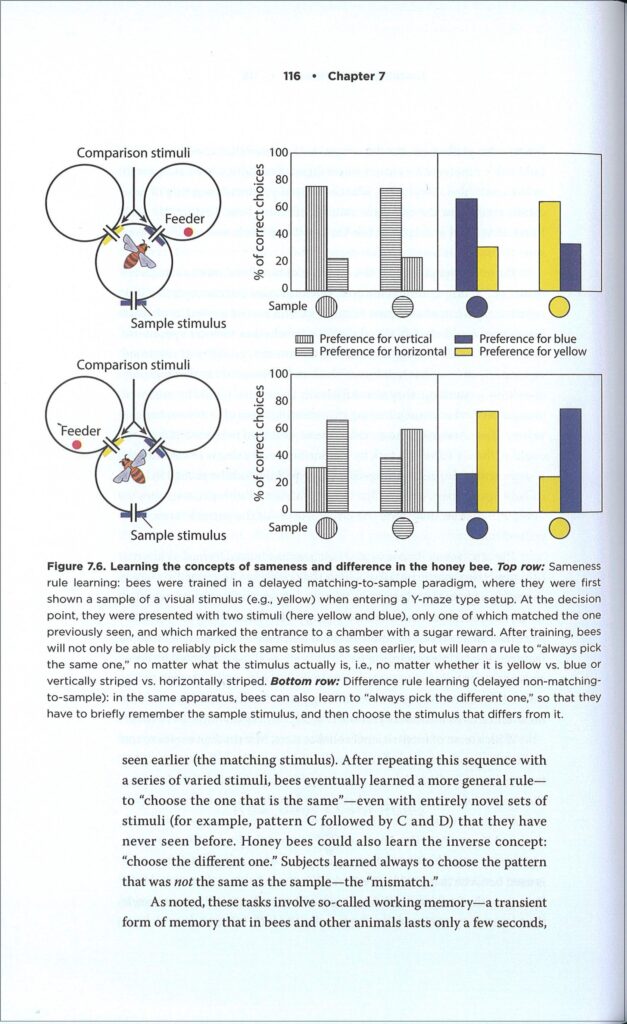

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarised light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153). What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty.

What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers but also, this was news to me, the location of potential nest sites when the swarm relocates. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50). What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers in choice experiments. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. Bumblebees would simply be lazy and check out both options in random order. Until, that is, protocols were modified by adding a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty. As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).

As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the Nazis. And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who snapped under pressure of not securing a permanent job and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).