Little Toller Books was established in 2008 as an imprint of Dovecote Press with the aim to revive lost classics of nature writing and British rural history. The success of their Nature Classics Library, has allowed them the independence to follow their inspiration in terms of the projects they pursue and they are now a leading voice in nature publishing. We asked Jon Woolcott of Little Toller Books about the Nature Classics Library.

The books are beautifully designed – what was the original inspiration behind the Nature Classics Library?

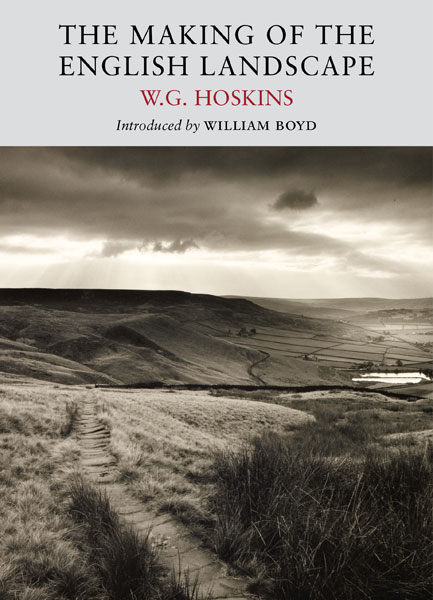

Thank you, that’s nice to hear – we work really hard at the design of the books, it strikes us that a book should be a beautiful object, and reflect the quality of the writing. The founders and co-owners of Little Toller, Adrian and Gracie Cooper, moved to Dorset but when they wanted to explore more about the country around their new home they found many of the books they wanted to read were no longer available. That inspired them to republish the great classics of nature writing – books like The Making of the English Landscape by W G Hoskins and The South Country by Edward Thomas. So Little Toller Books was born. The list has grown from there.

With introductions by big name authors giving them great general appeal, are you hoping to bring these classics to a new audience?

Indeed – we’re not the first generation to rediscover these great books – and bringing authors like William Boyd, Robert Macfarlane and Carol Klein to them makes a big difference. We also use artists to complement the writing – the obvious example is Ravilious on our edition of The Natural History of Selborne by Gilbert White, but we use artists to illustrate our monograph series.

How do you choose the books that end up on the list?

We’re a tiny team (there are just four of us at Little Toller) so we work together but ultimately Adrian chooses the books – it’s based on his taste and a sense of what readers are looking for, but always with the goal of exploring nature and our relationship with landscape.

If you could gain rights to publish any book from the history of nature writing, what would it be, and why?

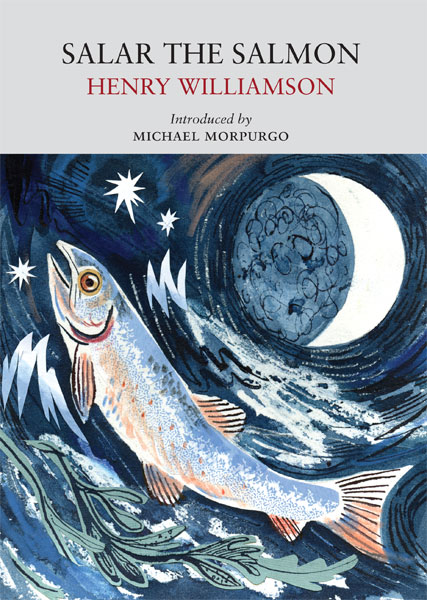

We’ve always got a wish-list on the go! We’d love to publish Tarka the Otter of course (we already publish Williamson’s Salar the Salmon) but a really exciting project would be to publish an anthology of Darwin’s letters recounting his explorations into his local area, and his relationship with his family. As yet, this remains in the pipeline though!

Do you remember the first natural history book that you enjoyed?

At Little Toller we all have our favourites, books that made an enormous difference to the way we felt or thought about nature. Speaking just for me I would highlight a book we don’t (yet!) publish – Bevis by Richard Jefferies. It’s not really a natural history book – ostensibly it’s a children’s book in the Swallows and Amazons tradition but written earlier. Jefferies brilliantly articulates the feelings of a boy as he explores the landscape. Jefferies was an early exponent of what we now call nature writing and I remember being captivated by his style. Adrian would choose On the Origin of Species because it’s so important, but for pure enjoyment he would have to go for Gerald Durrell’s My Family and Other Animals (editorial note: available as part of The Corfu Trilogy).

What do you think characterises great nature writing?

Oh, that’s a difficult question – each writer brings something new – but it’s characterised by a deep understanding of the subject combined with wonderful writing. A sense of the personal reaction to the natural world is imperative – we don’t publish text books but instead those which bring the reader close to the subject.

Little Toller also publishes new writing, with Horatio Clare’s Orison for a Curlew just out. What are you looking for in potential new publications like this?

We look for originality, for subjects which readers will love, and for wonderful writing. It’s led us to publish Oliver Rackham, Iain Sinclair and Richard Skelton this year alone.

What does the future have in store for Little Toller and the Nature Classics Library – any secrets you can let us in on?

We’re always looking to expand what we do – for instance we have two short films on our website about two of our books made by the authors – Iain Sinclair’s Black Apples of Gower and Richard Skelton’s Beyond the Fell Wall – and Andrew Kotting made Iain’s film with him. We’re tiny so we can be really flexible in what we publish but we’re especially excited by In Pursuit of Spring by Edward Thomas – which will have Thomas’ photographs from 1913 taken along the journey, published for the very first time – coming in March next year. We’re also looking forward to Cheryl Tipp’s book on the sounds of the sea. Many of NHBS’s fans will know her – she’s the Wildlife Sounds Curator at the British Library. And we have new books in the pipeline from Tim Dee, Dexter Petley and Horatio Clare, as well as new Nature Classics from R M Lockley and others. We’re also continuing to put our monographs into paperback as we have just done with The Ash Tree. We’re very busy! But we’re enormously heartened by the reaction to our books.

Browse the full list of books in Little Toller’s Nature Classics Library at NHBS

![Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland] Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Tommy-Karlsson-300x284.png)

![Onychogomphus foripatus description and distribution map from Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242_4.jpg)

![Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242.jpg)

Dr Dino Martins is an entomologist and evolutionary biologist with a PhD in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from Harvard University. He is also well-known in his native East Africa where he works to educate farmers about the importance of the conservation of pollinators. It is

Dr Dino Martins is an entomologist and evolutionary biologist with a PhD in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from Harvard University. He is also well-known in his native East Africa where he works to educate farmers about the importance of the conservation of pollinators. It is