The 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines is the latest update of the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT) Guidelines and features new content on biosecurity, night-vision aids, tree surveys and auto-identification for bat sound analysis. Several key chapters have been expanded, and new tools, techniques and recommendations included. It is a key resource for professional ecologists carrying out surveys for development and planning.

The 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines is the latest update of the Bat Conservation Trust (BCT) Guidelines and features new content on biosecurity, night-vision aids, tree surveys and auto-identification for bat sound analysis. Several key chapters have been expanded, and new tools, techniques and recommendations included. It is a key resource for professional ecologists carrying out surveys for development and planning.

Jan Collins is the Head of Biodiversity at the Bat Conservation Trust and a former ecological consultant. Her fascination in bats began when participating in a bat biodiversity survey on a Vietnamese expedition in 1999 and she has worked in bat conservation ever since. She has been in her current role for the last 10 years and has played a central role in the editing and refining of the BCT Guidelines.

In this Q&A we had the opportunity to speak with Jan about some of the key aspects of the 4th edition of the BCT Guidelines and its consequences for ecologists.

What led you towards a career specialising in bats?

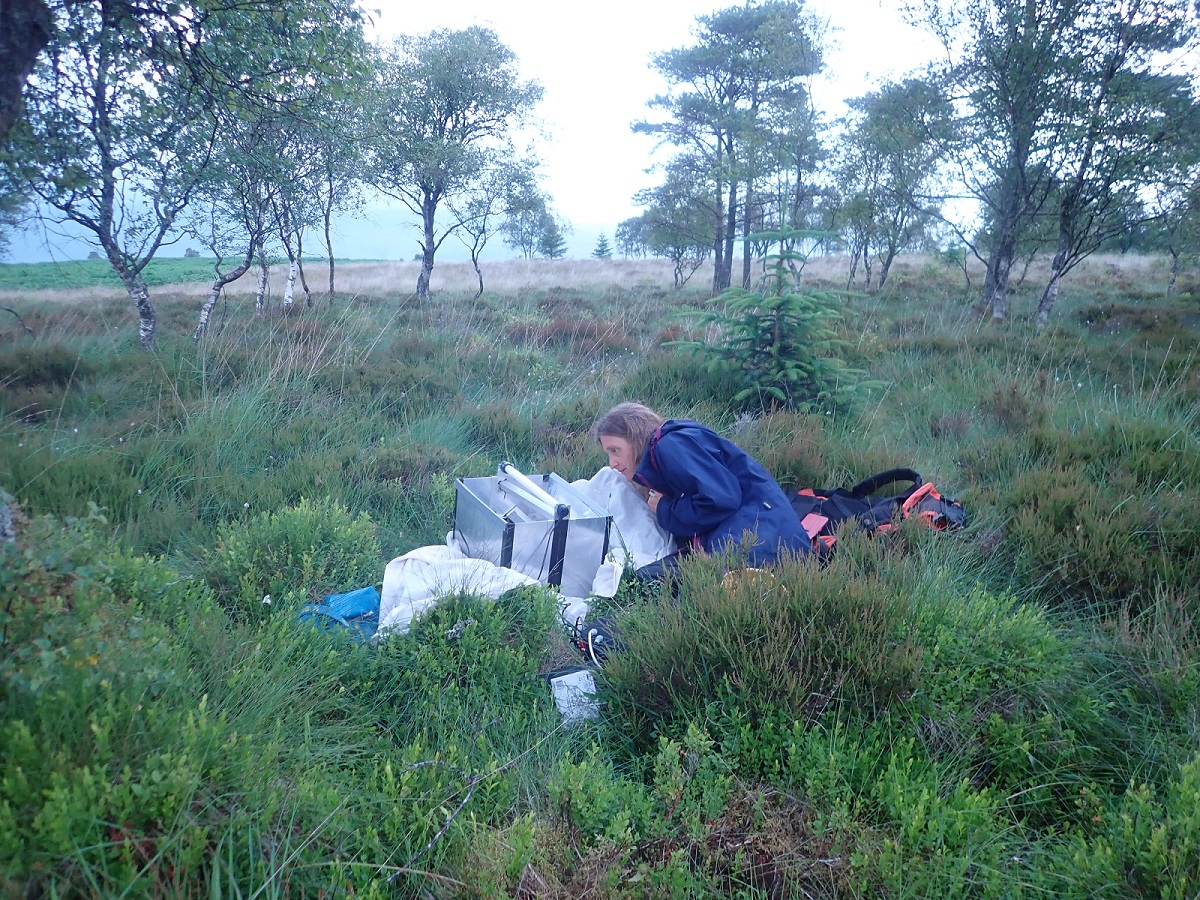

From a young age I was interested in being outdoors and engaging with nature. My studies followed this route, with a degree in Environmental Sciences and a Masters in Ecology and Management of the Natural Environment. I was first introduced to bats on a Frontier expedition to Vietnam in 1999 where we were trapping bats as part of a biodiversity survey. I was immediately hooked (what an amazing group of animals, with unique behaviours, and so very diverse!) and sought both voluntary and paid work involving bat conservation upon my return. I was an ecological consultant specialising in bats for over 10 years before joining Bat Conservation Trust in my dream job as Head of Biodiversity almost exactly 10 years ago now.

Could you tell us briefly about the work that the BCT does?

BCT is a dynamic, influential and growing national charity. We are the leading non-governmental organisation in the UK devoted solely to the conservation of bats and their environment. Our work represents the gold standard in bat conservation providing a lead for the rest of the world. We work to ensure that bat conservation is acknowledged as an integral part of sustainable development. Our work ranges from best practice guidance, advice and training through to engaging wider audiences so that we can get more people to understand the importance of bats and their conservation. A lot of our work also involves working with partners on the ground, local bat groups play a huge role in all aspects of our work. More information about all of our work can be found in the most recent annual review, found here or take a look at the Bat Conservation Trust Website here.

The 4th edition of Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines is due to be published in September 2023. What have been some of the key challenges in getting this ready for publication?

One of the key challenges for this edition was gaining consensus from the Technical Review Board on some of the recommendations. This included the continued use of transects for bat activity surveys and how tree surveys for bat roosts should be carried out, acknowledging the various limitations, and how approaches should be adapted to different types of projects. Another challenge has been how much to include on night vision aids such as infrared cameras. BCT are planning a kick-off meeting for a working group to develop separate night vision aid guidelines in the autumn (to include infrared and thermal imaging cameras) and therefore many aspects are still to be discussed and decided. We will also run a public consultation on night vision aids to help us to understand current practice and expectations from new guidelines on this topic.

How has the outlook for bat populations in the UK changed since the last edition of the Guidelines?

Data from the National Bat Monitoring Programme indicate that populations of the bat species we monitor in the UK are stable or recovering. However, it should be remembered that these trends reflect relatively recent changes in bat populations (since 1999 for most species). It is generally considered that prior to this there were significant historical declines in bat populations dating back to at least the start of the 20th century. This suggests that current legislation and conservation action to protect and conserve bats is being successful, and it is vitally important that this continues. Detailed information on trends for the 11 species monitored can be found in our National Bat Monitoring Programme reports here. We are also seeing signs of regional variations that deviate from the overall positive trend at the national level and we want to gain a better understanding of those. More data would help this process so we would encourage everyone to join in with one or more of the National Bat Monitoring Programme surveys. There are surveys that are suitable for anyone regardless of experience or equipment.

What are some of the key changes in the Guidelines?

A number of chapters have been expanded and new tools, techniques and recommended best practice incorporated. Below are a few of the changes but we will be developing a webinar in the coming months, detailing all of the changes so readers should watch out for that!

- A new section on Biosecurity has been added to Considerations for Bat Surveys chapter, recognising that precautionary approaches are needed to protect both ecologists and bats from potential health risks.

- Chapter 6 on Surveying Trees and Woodland for Bat Roosts has grown from five pages in the 3rd edition and now includes details of newer technologies and sources of information such as night vision aids, motion activated camera monitoring, The Bat Tree Habitat Key and the Bat Roost Tree Tag Project as well as updated guidelines for categorising the suitability of potential roost features.

- Chapter 7 focuses solely on dusk emergence surveys, with dawn re-entry surveys removed as a standard approach due to the improved quality of emergence surveys with night vision aids and the variability in the time that bats return to their roosts.

- Chapter 10 on Data analysis and Interpretation incorporates information on auto-identification systems and has a new section on data science which includes details on elements such as tidy data, minimal data requirement and data standardisation. There are also case studies to help illustrate key points.

How will the new Guidelines improve the way ecologists approach bat surveying?

The guidelines are the key resource for professional ecologists carrying out surveys for development and planning. The Biosecurity section in the 4th edition will ensure that ecologists carry out their work in a safe way, minimising health risks to both themselves and to bats. The latest edition acknowledges the constraints involved in surveying trees for bat roosts and offers different approaches to surveys depending on the nature, scale and timeline of the project. A new categorisation system for Potential Roost Features (PRFs) and trees reduces the subjectivity in initial assessments of trees. Dawn re-entry surveys are no longer recommended as there are questions around their efficacy for presence/absence and because emergence surveys can be vastly improved by the use of night vision aids. A stepwise approach is offered to those using auto-identification systems to analyse acoustic datasets and the section on Data Science aims to standardise approaches to data management. The guidelines also make reference to a wealth of resources that can be used to improve surveys and, in particular, interpretation of survey data.

Nocturnal survey equipment such as night vision, thermal imaging and infrared cameras are becoming more important in bat survey with the 2022 Interim Guidance Note providing clarification of their role. How will the 4th edition of the Guidelines impact the way ecologists conduct bat surveys using these types of equipment?

The 4th edition supercedes (but is consistent with) the Interim Guidance Note published in May 2022. It emphasises that surveys should usually be carried out with night vision aids and that if they are not used this should be justified in reporting, with reasons provided (e.g. at known roosts when bats are known to emerge early or in situations/locations with higher levels of natural or artificial light). Dawn re-entry surveys are no longer recommended as a standard approach because the use of night vision aids vastly improves the quality of emergence surveys, when used properly. The new guidelines state that a still shot must be taken at the darkest point of the survey to show the field of view and that appropriate illumination has been used. They suggest that the use of night vision aids can be used to reduce the number of surveyors but only if the cameras/lighting reliably match or exceed what a surveyor can achieve, with evidence provided. See the 4th edition for more information on use of this equipment!

BCT are planning a kick-off meeting for a working group to develop separate night vision aid guidelines (with much more detail) in the autumn (to include infrared and thermal imaging cameras) and therefore many aspects are still to be discussed and decided. We will also run a public consultation on night vision aids, to help us to understand current practice and expectations from new guidelines on this topic.

Bat Surveys for Professional Ecologists: Good Practice Guidelines is now available to pre-order from nhbs.com.

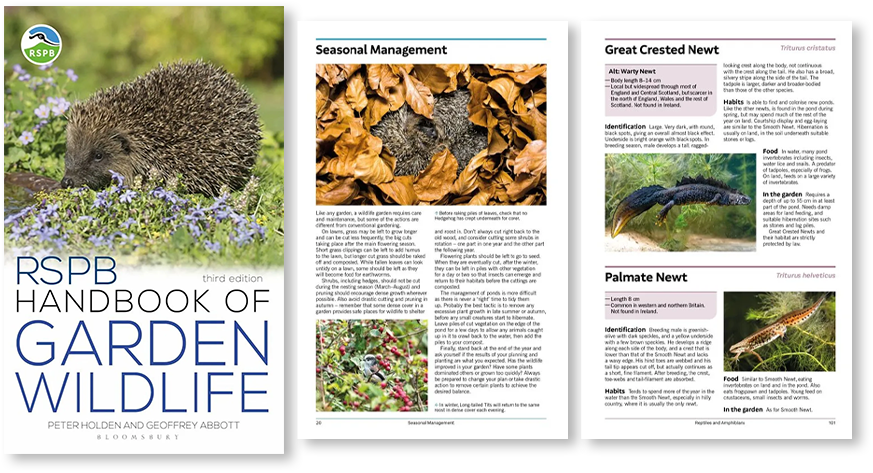

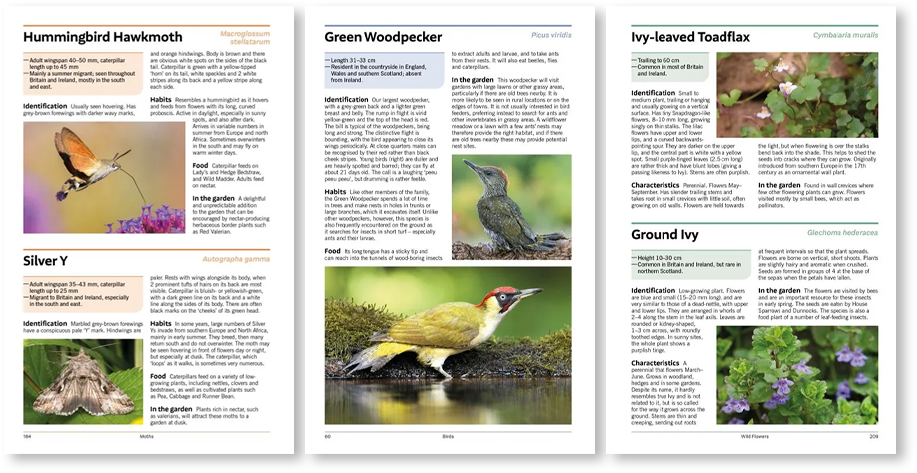

I’m a big fan of all insects (and other invertebrates) and generally, as long as I’m learning new things, I’m happy. However, with moths, I love that you don’t need a microscope to enjoy their beautiful variety and a light trap means many species can be enjoyed relatively easily. It’s hard not to be impressed by the stature of a Poplar Hawk-moth or the delicacy of a White Plume Moth. They are also great insects to share with others; excellent ambassadors for our often-overlooked smaller fauna.

I’m a big fan of all insects (and other invertebrates) and generally, as long as I’m learning new things, I’m happy. However, with moths, I love that you don’t need a microscope to enjoy their beautiful variety and a light trap means many species can be enjoyed relatively easily. It’s hard not to be impressed by the stature of a Poplar Hawk-moth or the delicacy of a White Plume Moth. They are also great insects to share with others; excellent ambassadors for our often-overlooked smaller fauna. Yes, I think so, particularly in archives with accompanying notes and diaries. Just as contemporary recorders have slightly different motivations; for example seeing as many species as possible or understanding the moths of a particular area well, so did collectors from the past. The details that are written on the labels, the handwriting, the comments in notebooks all hint at the personality of the characters involved. I’m not sure our modern legacy of spreadsheets and digital photo archives provide the same back story. Of course in many cases – a bit like social media feeds – only the significant finds and achievements get documented for prosperity. Failures are brushed aside and conveniently forgotten.

Yes, I think so, particularly in archives with accompanying notes and diaries. Just as contemporary recorders have slightly different motivations; for example seeing as many species as possible or understanding the moths of a particular area well, so did collectors from the past. The details that are written on the labels, the handwriting, the comments in notebooks all hint at the personality of the characters involved. I’m not sure our modern legacy of spreadsheets and digital photo archives provide the same back story. Of course in many cases – a bit like social media feeds – only the significant finds and achievements get documented for prosperity. Failures are brushed aside and conveniently forgotten.