Late autumn and winter are the ideal time for planting trees and hedgerows. In this article we provide lots of tips for the first time tree-planter and point you in the direction of heaps of helpful information to ensure that your trees and shrubs get off to the best start this year.

Why is winter the best time to plant trees?

During the winter, trees are mostly dormant. This means that their aerial parts are not actively growing. However, below the ground is a different story. Trees use this period of dormancy to create an expansive root network which will work hard throughout the year to provide the plant with plenty of water and nutrients. Planting the tree during the late autumn and winter gives it plenty of time to build up a strong root structure in time for spring. Soil also tends to be softer and moister during the colder months, which helps the tree to expand and grow its roots. Plus, there is much less competition from weeds and grass, so your sapling has a better chance of establishing successfully.

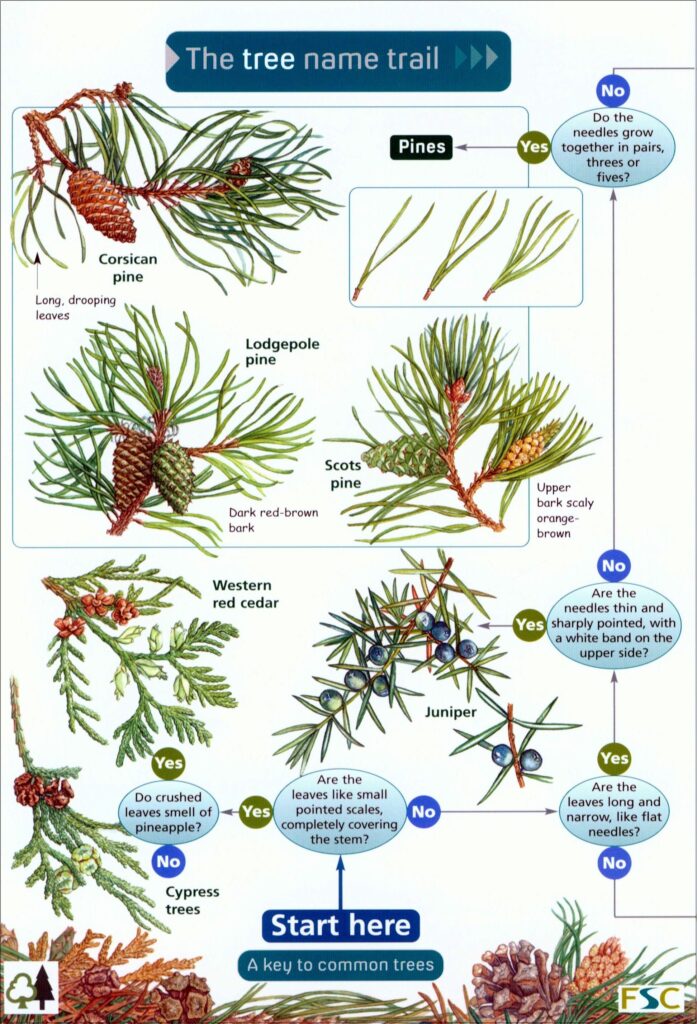

Which species should I plant?

The species of tree you wish to plant will depend largely on where you want to put it. Is it going to be part of a hedgerow or will it stand on its own? How much space do you have, and how big is the tree likely to grow? For example, if you are planting in a small garden, you don’t want a tree that will grow too large or where it will end up shadowing your own or someone elses land or house. Don’t forget that a tree’s root system can grow much larger than its canopy, so planting near to buildings can become a problem later down the line.

A good rule of thumb is to take note of the trees that are growing and thriving locally, as these will be species that are suited to the local conditions. Choosing native varieties is also important, as these will help to support lots of wildlife such as birds, bees and butterflies. There are more than 60 species of native tree and shrub in the UK, so there’s plenty to choose from!

Where do I get my tree(s) from?

Trees and hedgerow plants are widely available from garden centres and tree nurseries. Make sure to check that trees have been grown in the UK, as trees imported from overseas are at risk of being contaminated with exotic pests and diseases. Trees of different ages will be available and your choice will depend largely on your budget and means of transportation. The main types are:

Transplants – Young seedlings that have been started in a tree nursery then dug up, ready to be transplanted in their final location. You may hear these referred to as a ‘whip’ – this is a transplant that doesn’t yet have any branches. (As the name suggests, this can look, rather unpromisingly, like a slim twig).

Standard – A larger tree which has a head of branches. Usually these trees will be over two metres in height, meaning that transportation can be more of an issue.

Heavy standard – Similar to the standard, these trees will also have a head of branches but will be older and larger; usually over three metres in height.

Semi-mature – These are well-established trees which are likely to be at least 10-15 years old. They tend to be four metres or more in height and so are generally more suited to commercial or larger-scale planting projects.

Transplants and whips are likely to be sold either in their own containers or with bare roots. Standards, heavy-standards and semi-mature trees, however, are usually ‘root-balled’ which means that their roots will be covered in soil and then wrapped in hessian for safe transportation.

Another option is to grow your own trees from seeds collected in the wild. As well as being hugely satisfying, this option has the benefit of being free! The Conservation Volunteers website has lots of information on collecting, extracting, sowing and growing your tree seeds, including a comprehensive handbook that is free to download.

How do I plant my tree?

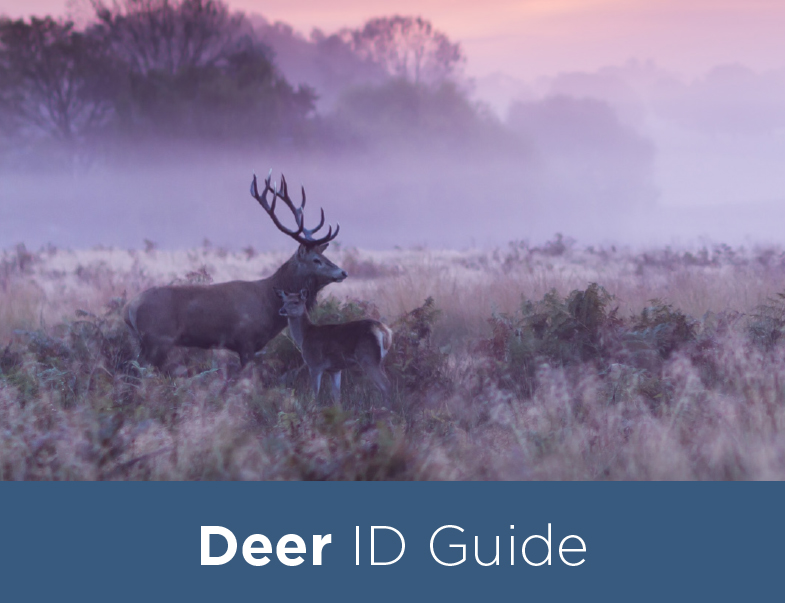

Trees should be transplanted as soon as possible after purchase. For small trees you can simply use a spade to cut a T-shape in the soil, pressing in the spade to the same depth as you wish the roots to go. By peeling back the turf at the central point of the T, you can insert your transplant or whip and then press the turf back into place, making sure that the soil is well packed around the roots. Hedge plants can be planted using the same technique, either in a single or double row. Plants should be placed around 30cm apart in a single row or 50cm apart in a staggered double row. Applying a thick layer of mulch around the base of the tree will help to conserve moisture and prevent weed growth – but don’t let the mulch touch the tree itself, as this can encourage mould and decay. You may also need to fit a tree guard if you are planting young trees in an area where animals such as deer or rabbits could be a problem.

For larger trees, you will need to dig a hole that is large enough for the roots to spread out. If the soil is poor you may wish to dig a larger hole and then add some good quality compost before planting the tree. Tease out the roots if they are compacted or wound up and then place the tree gently in the hole. Once you have back-filled the hole with soil, it is important to ‘tread-in’ the plant so that the soil is firm around the base and roots. Apply a layer of mulch in a 1m diameter around the tree after removing any grass or weeds if necessary.

All newly planted trees should be watered immediately.

What now? Do I need to look after my tree?

Although the hard work is now done, it is important to check on your tree at least once a year to make sure that it is growing and thriving. Particularly with young trees, it may be necessary to water regularly in the summer or during any particularly dry periods. During the first three years it is also worth weeding by hand around the base of the tree to minimise competition for water and nutrients. Applying a thick mulch will also help to control weeds – leaf litter, lawn clippings or composted bark are great organic options.

Further information

• National Tree Week – In 2022 National Tree Week takes place on 26th November to the 4th December. Take the opportunity to get involved by planting your own tree, or get in touch with your local Tree Warden Network to see if there are any organised tree plantings happening where you live.

• Autumn Seed Harvest Handbook – This great handbook from The Conservation Volunteers provides all the information you need to collect, process and plant a tree from seeds found in your own neighbourhood.

• Twigged! – This great booklet from the Woodland Trust provides lots and lots of information on our native trees and how to recognise them throughout the year.

• Royal Horticultural Society website – The RHS website has a wealth of information on tree species that will help you to choose the right kind for your garden or planting project.

Recommended reading

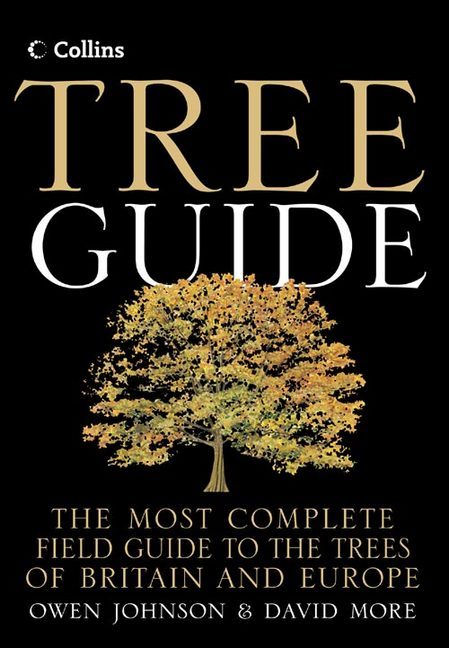

The Collins Tree Guide is a definitive, fully illustrated guide to the trees of Britain and non-Mediterranean Europe, containing some of the finest original tree illustrations ever produced. Within each tree family there is a list of key species and a guide to the most important features to look for.

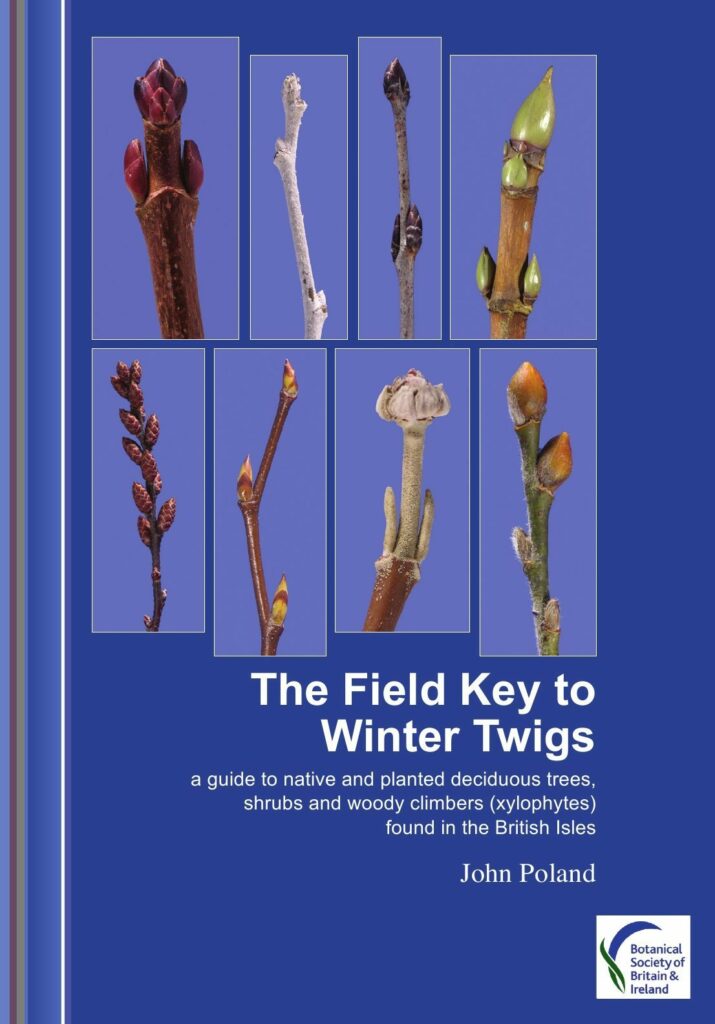

The Field Key to Winter Twigs

The Field Key to Winter Twigs offers a striking new approach to the identification of over 400 wild or planted trees, shrubs and woody climbers in the British Isles. It allows any diligent enthusiast to reliably name a woody plant, normally within three turns of pages and often within a minute of study.

Produced with the support of the Forestry Commission, this 12-page laminated fold-out chart contains a full-colour illustrated key to the leaves, twigs, fruits and seeds of the commonest broadleaved and coniferous trees of Britain and Ireland.

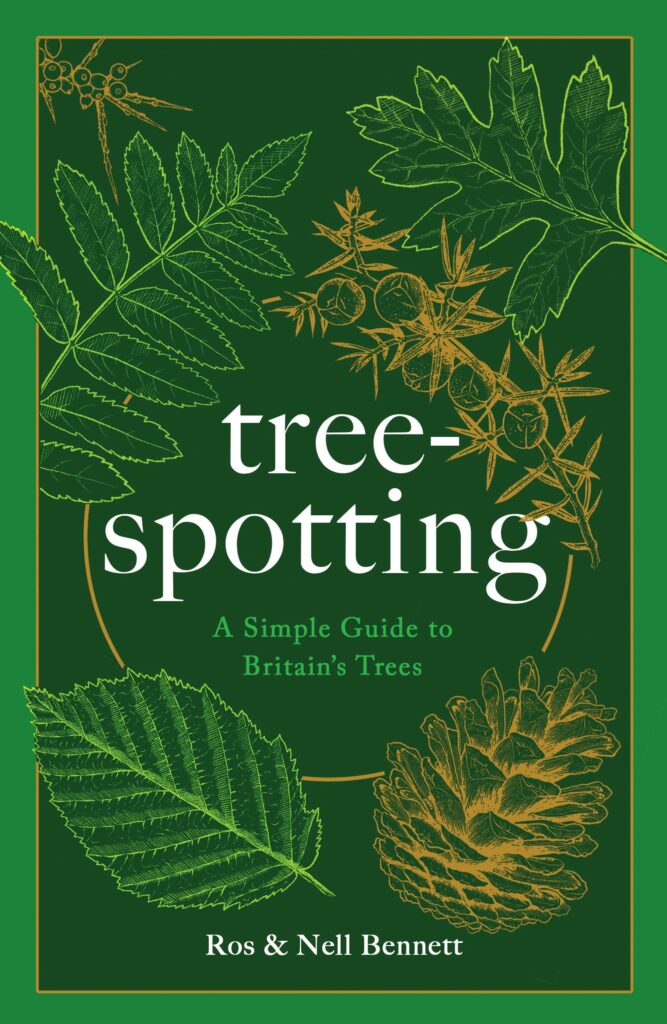

Tree-Spotting: A Simple Guide to Britain’s Trees

Tree-Spotting: A Simple Guide to Britain’s Trees

A beautiful and captivating insight into the wonderful world of trees, Tree-Spotting burrows down into the history and hidden secrets of each species. It explores how our relationship with trees can be very personal, and hopes to bring you closer to the natural world around you.

As a zoological professional you have studied and worked in several esteemed organisations including the University of Bristol, London Zoo and Oxford-Brookes University. What do you consider to be the most significant highlights of your career so far?

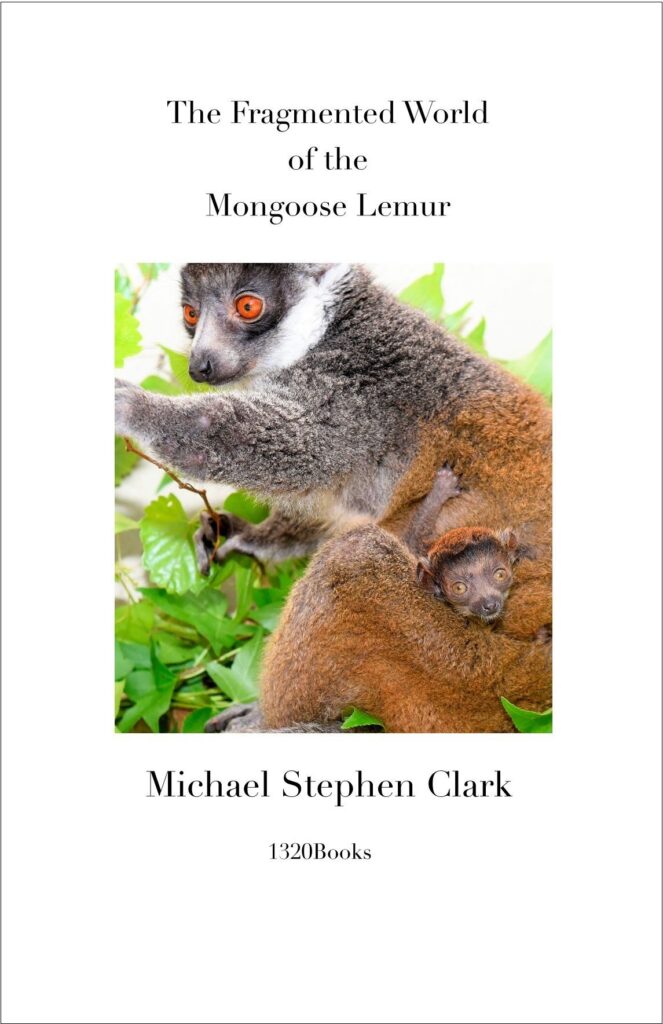

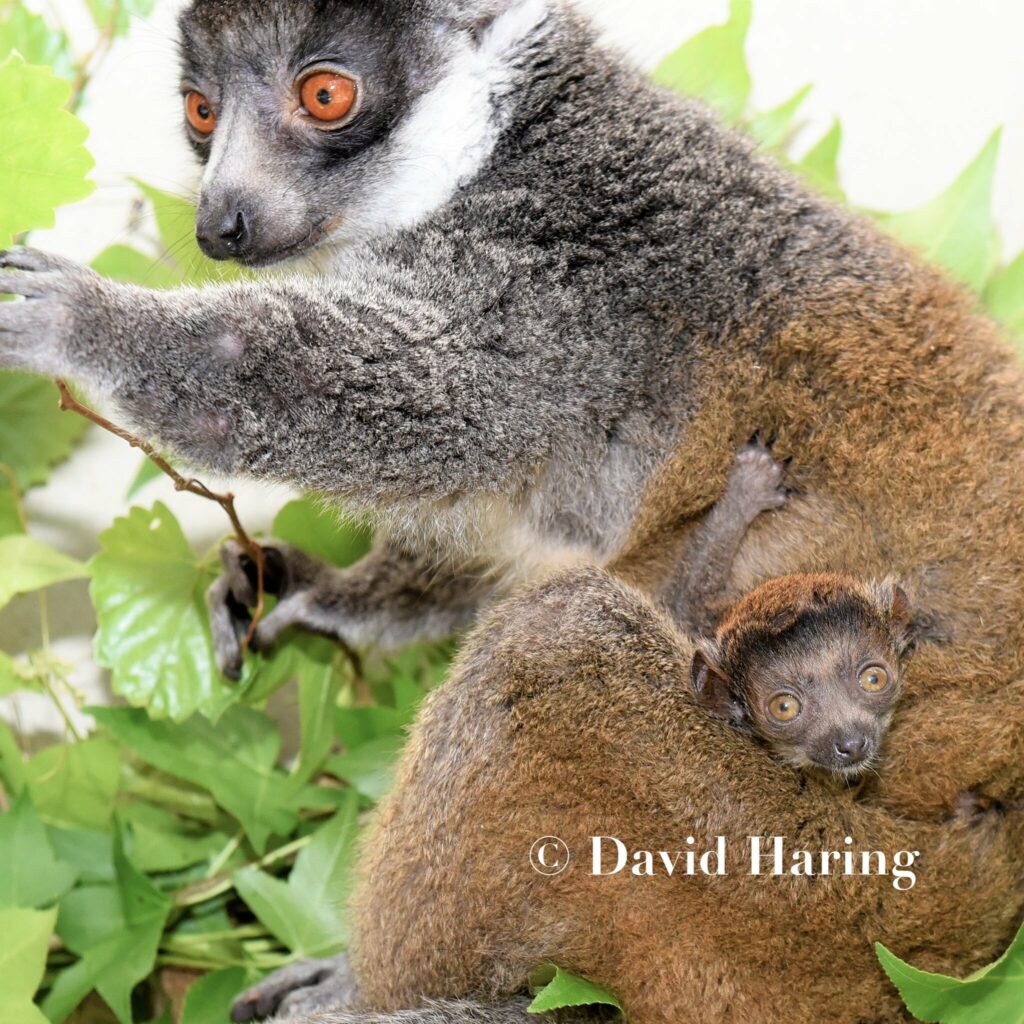

As a zoological professional you have studied and worked in several esteemed organisations including the University of Bristol, London Zoo and Oxford-Brookes University. What do you consider to be the most significant highlights of your career so far? The Fragmented World of the Mongoose Lemur is, in large part, a species-specific natural history – a format that is perhaps less popular than it has been in previous years and decades. The book was also published independently. How did you find the process of planning, writing and publishing the book and what were the main challenges you faced?

The Fragmented World of the Mongoose Lemur is, in large part, a species-specific natural history – a format that is perhaps less popular than it has been in previous years and decades. The book was also published independently. How did you find the process of planning, writing and publishing the book and what were the main challenges you faced?

• Peaking in late November and early December, Starling murmurations are one of the most spectacular events in the wildlife watcher’s year. These magnificent clouds of birds, swirling and turning in perfect unison, can be made up of more than 100,000 individuals. The best time to see murmurations is in the early evening – this is when the birds take to the skies to find their night-time roosting spots.

• Peaking in late November and early December, Starling murmurations are one of the most spectacular events in the wildlife watcher’s year. These magnificent clouds of birds, swirling and turning in perfect unison, can be made up of more than 100,000 individuals. The best time to see murmurations is in the early evening – this is when the birds take to the skies to find their night-time roosting spots. • October is the ideal time to observe the deer rut. Our three largest species of deer (red, fallow and sika) all perform this spectacular behaviour which involves rival stags roaring and locking antlers in battle in order to gain access to females, who are only fertile for around one day each year. Exmoor, Dartmoor and the New Forest are particularly good locations for observing these iconic displays.

• October is the ideal time to observe the deer rut. Our three largest species of deer (red, fallow and sika) all perform this spectacular behaviour which involves rival stags roaring and locking antlers in battle in order to gain access to females, who are only fertile for around one day each year. Exmoor, Dartmoor and the New Forest are particularly good locations for observing these iconic displays. • During the autumn, salmon will migrate from the open ocean back to their home rivers in an effort to reach the higher reaches of clean water where they will breed. As they travel upstream they can jump up to three metres upon encountering waterfalls or other obstacles. Although risky for the fish, as jumping out of the water makes them vulnerable to predation, these spots provide an excellent chance for us to observe the salmon run in action.

• During the autumn, salmon will migrate from the open ocean back to their home rivers in an effort to reach the higher reaches of clean water where they will breed. As they travel upstream they can jump up to three metres upon encountering waterfalls or other obstacles. Although risky for the fish, as jumping out of the water makes them vulnerable to predation, these spots provide an excellent chance for us to observe the salmon run in action.