On 6th November, a date that marks the 800th anniversary of the 1217 Charter of the Forest, a new Charter for Trees, Woods and People will be launched. Read on to find out more, including the 10 principles of the Tree Charter and information on how to get involved.

Led by the Woodland Trust, the Tree Charter brings together more than 70 organisations in a united effort to protect the rights of and relationships between trees and people in the UK.

The Charter will be launched on 6th November at Lincoln Castle. This date marks the 800th anniversary of the historic 1217 Charter of the Forest which set out the rights of the people to use the Royal Forests in England. Lincoln Castle is home to one of the only two surviving copies of this document, making the timing and location of the launch doubly momentous.

The new Tree Charter is intended to influence policy and practice by settings out the practical roles and responsibilities of individuals, businesses and government in the UK and will also provide a voice for the hundreds of thousands of people that it represents.

The Charter consists of 10 Principles which cover different aspects of protecting and celebrating our trees. During National Tree Week (beginning Saturday 25th November) ten Tree Charter poles – one for each of the 10 Principles of the Charter – will be unveiled across the UK.

The 10 principles can be read in detail below, along with the locations of the charter poles.

The 10 Principles of the Tree Charter

(Reproduced from https://treecharter.uk)

1. Thriving habitats for diverse species (New Forest Visitor Centre)

Urban and rural landscapes should have a rich diversity of trees, hedges and woods to provide homes, food and safe routes for our native wildlife. We want to make sure future generations can enjoy the animals, birds, insects, plants and fungi that depend upon diverse habitats.

2. Planting for the future (Burnhall, Durham)

As the population of the UK expands, we need more forests, woods, street trees, hedges and individual trees across the landscape. We want all planting to be environmentally and economically sustainable with the future needs of local people and wildlife in mind. We need to use more timber in construction to build better quality homes faster and with a lower carbon footprint.

3. Celebrating the cultural impact of trees (Bute Park, Cardiff)

Trees, woods and forests have shaped who we are. They are woven into our art, literature, folklore, place names and traditions. It’s our responsibility to preserve and nurture this rich heritage for future generations.

4. A thriving forestry sector that delivers for the UK (Sylva Wood Centre, Abingdon)

We want forestry in the UK to be more visible, understood and supported so that it can achieve its huge potential and provide jobs, forest products, environmental benefits and economic opportunities for all.

Careers in woodland management, arboriculture and the timber supply chain should be attractive choices and provide development opportunities for individuals, communities and businesses.

5. Better protection for important trees and woods (Sherwood Forest, Nottingham)

Ancient woodland covers just 2% of the UK and there are currently more than 700 individual woods under threat from planning applications because sufficient protection is not in place.

We want stronger legal protection for trees and woods that have special cultural, scientific or historic significance to prevent the loss of precious and irreplaceable ecosystems and living monuments.

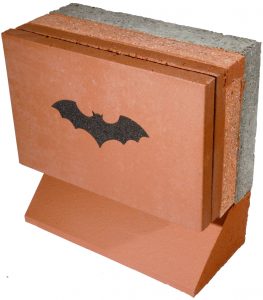

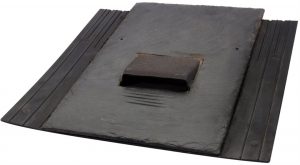

6. Enhancing new developments with trees (Belvoir Wood, NI)

We want new residential areas and developments to be balanced with green infrastructure, making space for trees. Planning regulations should support the inclusion of trees as natural solutions to drainage, cooling, air quality and water purification. Long term management should also be considered from the beginning to allow trees to mature safely in urban spaces.

7. Understanding and using the natural health benefits of trees (Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, Liverpool)

Having trees nearby leads to improved childhood fitness, and evidence shows that people living in areas with high levels of greenery are 40% less likely to be overweight or obese. We believe that spending time among trees should be promoted as an essential part of a healthy physical and mental lifestyle and a key element of healthcare delivery.

8. Access to trees for everyone (City Forest Park, Manchester)

Everyone should have access to trees irrespective of age, economic status, ethnicity or disability. Communities can be brought together in enjoying, celebrating and caring for the trees and woods in their neighbourhoods. Schoolchildren should be introduced to trees for learning, play and future careers.

9. Addressing threats to woods and trees through good management (Land Craigs)

Good management of our woods and trees is essential to ensure healthy habitats and economic sustainability. We believe that more woods should be better managed and woodland plans should aim for long term sustainability and be based upon evidence of threats and the latest projections of climate change. Ongoing research into the causes of threats and solutions should be better promoted.

10. Strengthening landscapes with woods and trees (Grizedale Forest, Cumbria)

Trees and woods capture carbon, lower flood risk, and supply us with timber, clean air, clean water, shade, shelter, recreation opportunities and homes for wildlife. We believe that the government must adopt policies and encourage new markets which reflect the value of these ecosystem services instead of taking them for granted.

• Firstly and most importantly – sign the Tree Charter. By adding your signature you will show your support for the principles stated in the charter and will join the growing list of 1000s of people who want to see trees protected, shared and celebrated in the UK. The Woodland Trust will plant a tree for every signature on the list and will also use your contact details to keep you up to date with the campaign.

• Use social media to spread the word. Use #TreeCharter, #StandUpForTrees and #CharterOfTheForest in your posts, and link to the Tree Charter Thunderclap: https://www.thunderclap.it/projects/62126-the-tree-charter-is-launching

• Join a local Charter branch. Join an existing group or, if there isn’t one near to where you live, set up your own. Charters can apply for funding from the Woodland Trust and will receive free copies of the seasonal newspaper LEAF! As a charter branch you will also be able to apply for a Legacy Tree. 800 of these trees are being planted around the UK as a living reminder of the 800 years between the original 1217 Charter of the Forest and the 2017 Tree Charter. Each tree will be supplied with a commemorative plaque.

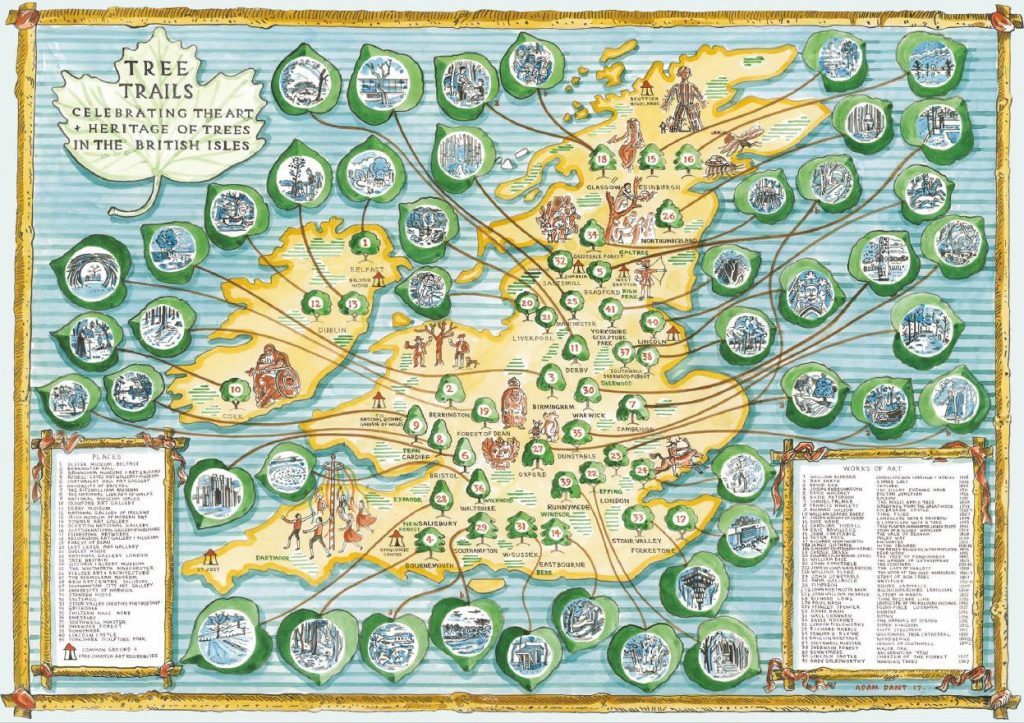

• Explore some of the locations on the Tree Charter Art and Heritage Trail. All locations are displayed on a beautifully illustrated map by Adam Dant, highlighting the role that trees have played in the culture and heritage of our country.

Woodland Reading:

Collins Tree Guide

Woodland Management: A Practical Guide

Winter Trees: A Photographic Guide to Common Trees and Shrubs

Trees: A Complete Guide to Their Biology and Structure

Woodland Development: A Long-Term Study of Lady Park Wood

Oak and Ash and Thorn: The Ancient Woods and New Forests of Britain

The Company of Trees: A Year in a Lifetime’s Quest

Kaleidoscope Pro is now available as an

Kaleidoscope Pro is now available as an

2.

2.

7.

7.

4.

4.