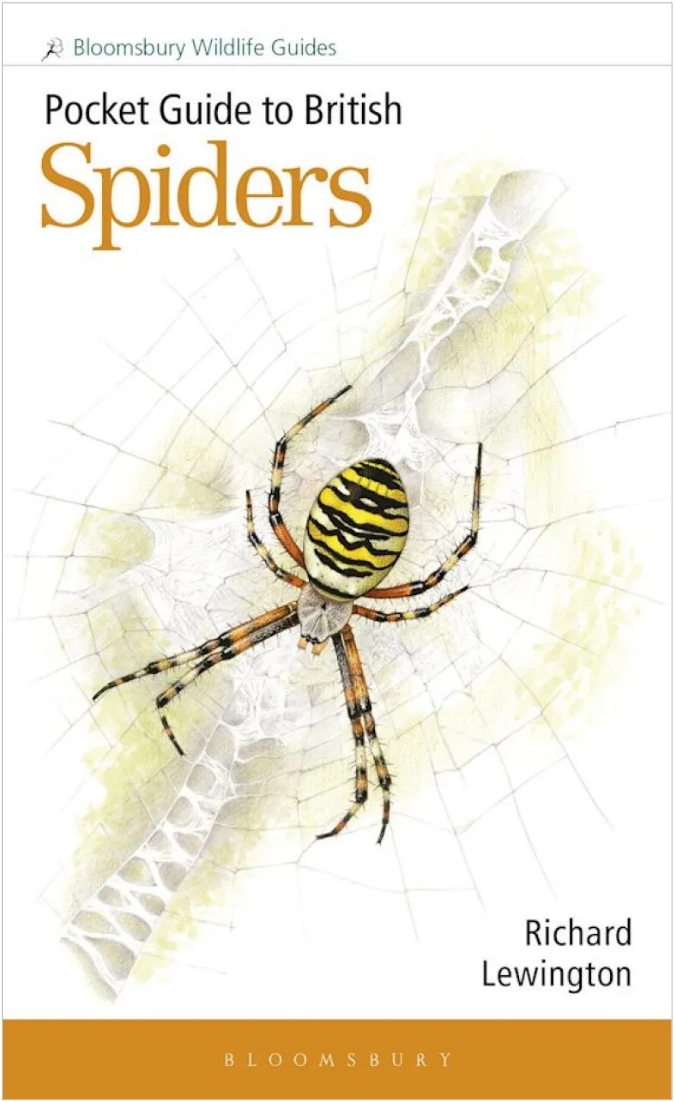

In this radical, eye-opening book, environmentalist Tony Juniper CBE explores the interconnectedness of the environmental crisis and inequality, and argues that ecological progress cannot be achieved without addressing these disparities. Collating a range of interviews with global experts, and drawing upon 40 years of research and campaigning, he provides long-overdue answers as to how we can achieve real, lasting change.

In this radical, eye-opening book, environmentalist Tony Juniper CBE explores the interconnectedness of the environmental crisis and inequality, and argues that ecological progress cannot be achieved without addressing these disparities. Collating a range of interviews with global experts, and drawing upon 40 years of research and campaigning, he provides long-overdue answers as to how we can achieve real, lasting change.

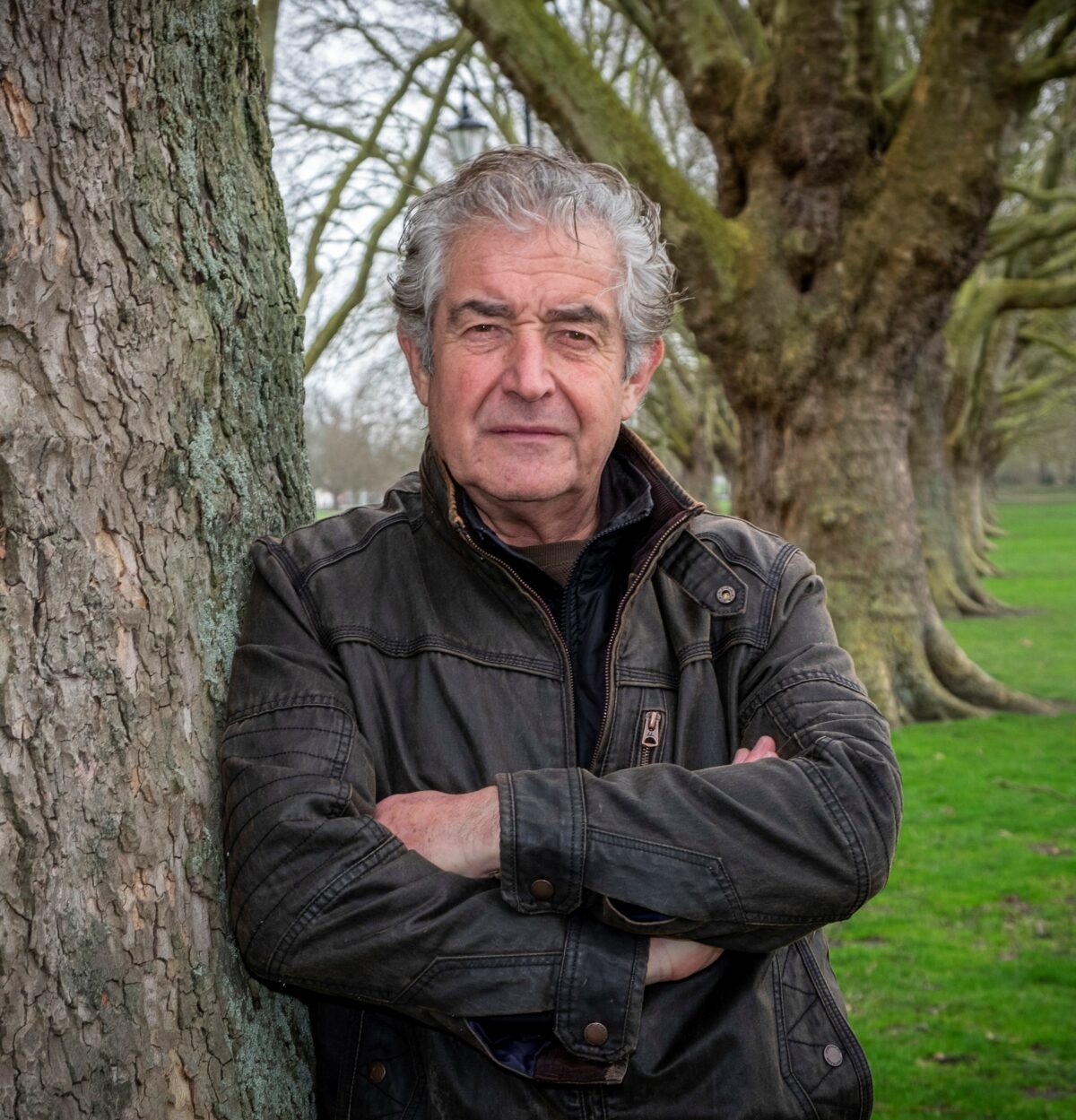

Tony Juniper CBE is an environmental advocate who has been active in defending nature for nearly 40 years, through leading major organisations, managing global campaigns, and holding high-level government advisory roles. He is a celebrated author, known for numerous award-winning titles, and was awarded a CBE in 2017 as recognition for his contributions to conservation.

We recently had the opportunity to speak to Tony about his book, where he told us about the most challenging aspects of writing Just Earth, the importance of technology in creating a sustainable future and more.

Firstly, can you tell us a little about yourself and what inspired you to write this book?

I am a long-serving environmental advocate. I have led and advised campaigns and campaigning organisations, worked as a professional ornithologist, worked with the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, written some books and I now lead Natural England – the UK government’s nature agency in England.

What message are you hoping to convey with Just Earth, and what do you hope the reader may learn from its message?

Just Earth set outs why and how various kinds of social inequalities are massive environmental issues. This is seen in how the poorest and voiceless get hit first and hardest by environmental damage, including exposure to toxic pollution, lack of access to good quality green spaces and the effects of climate change. Those most affected are the groups who are least responsible for causing such damage in the first place. The injustices linked with this limit the agreement of strong global accords and blocks action in countries around the world – new environmental laws and policies are held back because of the plight of the poor, who during cost of living crises are held up as the reason not to increase costs through moves to sustainable farming and clean energy, for example. Inequality also destroys the trust needed to foster the common endeavour that is so vital for fixing complex global issues. I set out something on what might be done, but it is a big set of challenges that we are facing, and the book seeks to inform the reader about the breadth and depth of what is at hand.

What was the most challenging aspect of writing Just Earth?

It is a complex story that the book seeks to tell. Getting the facts and data woven into a readable and balanced narrative was hard work – I am pleased with the result though, and hope readers will find it interesting and informative.?

Green growth explores the possibility of decoupling the expansion of gross domestic product (GDP) with environmental damage. How important do you think technology will be in a green growth scenario, and do you think technological innovation can truly pave the way for a greener, more sustainable future?

Technology is a vital component of what is needed, but we’ve had a lot of that for decades and not used it at the scale needed. Just Earth sets out why it is important to look beyond solar panels, AI, batteries and all the rest, and looks into the social and political context in which these technologies are deployed. The idea of green growth has been around for years but there are too few examples of it working in practice. One challenging aspect that runs counter to our consumerist culture is the need to use less stuff. We are already causing massive environmental damage with a minority of the world population living like Europeans, and we simply don’t have enough planet to keep growing as we have during past decades – even if it is a bit greener here and there.

Chapter 11 sets out a ten-point agenda for a just transition to a secure future. If any, which of these do you believe should be the primary focus in beginning this transition, and how long do you think it will take to achieve?

I think the biggest single thing, which links to the idea of green growth, is to change what we are measuring as growth. At present, gross domestic product (GDP) dominates but fails to take account of the environmental damage and inequalities that go with it. Coming up with more comprehensive measures of growth, that also include metrics linked with social wellbeing, ecological footprint, happiness, health and social cohesion would lead to different outcomes. There are ways of doing this, and in the book, I touch on the idea of a Genuine Progress Indicator, which measures far more than simply how much economic activity is taking place.?

What gives you hope for the future of our planet??

We are in revolutionary times and at a moment when the old ideas of the 20th century are facing serious tests. Environmental goals are being diluted and weakened by some governments and companies and democracies showing signs of stresses and strains that have profound implications. My hope is that during the turbulent times that we are in new ideas will begin to take hold. I propose a new frame of reference to go beyond capitalism or socialism and to instead embrace the idea of Thrivalism, a world view that would aim to create the conditions for ten billion people to thrive and enjoy long and happy lives on a living planet. At this point we need to think big.

What’s next for you? Are you writing any other books we can hear about?

I have various projects in mind, and more will be shared on those in due course. For now, promoting the ideas in Just Earth will I expect take up quite a lot of time, alongside all the other things I do.

Just Earth is available to order from our bookstore here.