Climate change

New Zealand farmers have suggested that the government should impose a levy on agricultural gas emissions to encourage the reduction of methane and nitrous oxide emissions. The government had legislated that farmers must develop an emissions pricing system or agriculture would automatically enter the country’s emissions trading scheme. Grassroots farms have been protesting in recent years against the introduction of environmental regulations, but agriculture currently generates over half of New Zealand’s industrial and household emissions. The sector has been facing significant political pressures over this disproportionate contribution to climate change.

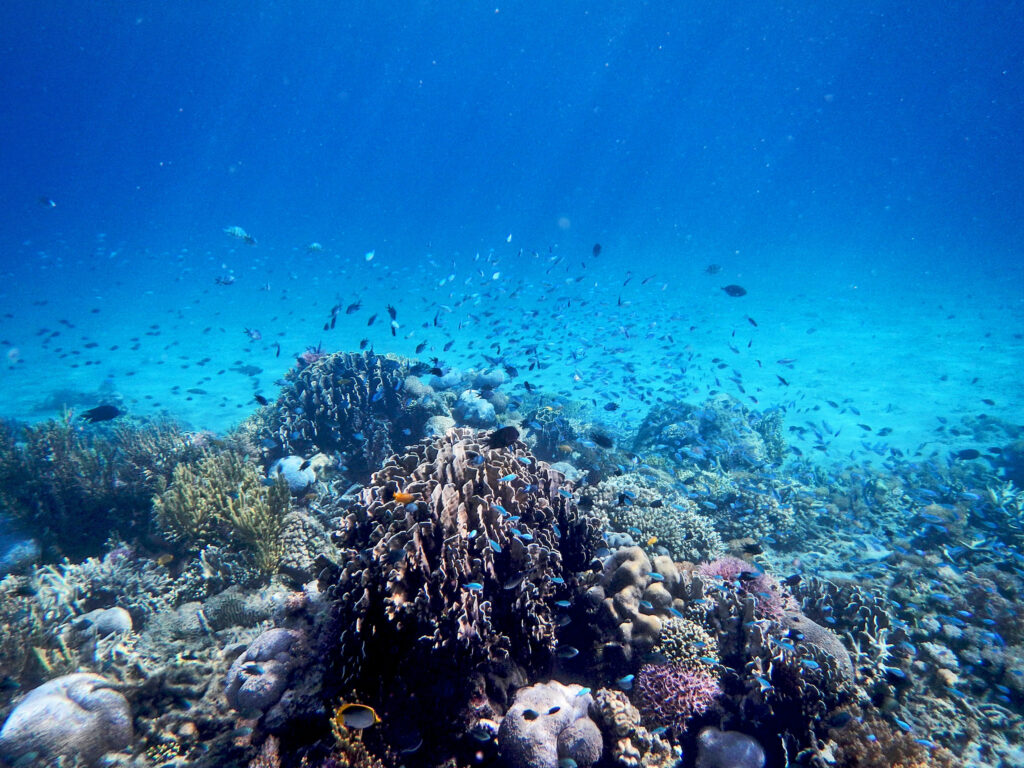

Climate change is impacting whale habitat use in the Gulf of Maine. Warming waters has caused right and humpback whales to shift their use of Cape Cod Bay over the last 20 years. Using aerial surveys conducted from 1998 to 2018, the research team analysed environmental data to study changes in whale habitat use within and across years. The peak use of Cape Cod Bay by these species has sifted almost three weeks later, related to the arrival of spring, which has been changing due to climate change. Right whales may be using Cape Cod Bay for longer periods because climate change has reduced the amount of food available in other Gulf of Maine habitats.

Conservation

For the first time in 30 years, Zoo Atlanta has successfully hatched a Critically Endangered Bog Turtle. This species, Glyptemys muhlenbergii, is the smallest turtle in North America and has only been documented in 10 states in the US. The zoo’s captive breeding program includes one male and two females, which the zoo reports are still young to have reproduced.

Research

A new study has estimated that 44% of Earth’s land is needed to stop the biodiversity crisis. Environmentalists have been lobbying governments to commit to protecting 30% of Earth’s land, but this may not be enough. A computer-generated global map has been created, showing the most efficiently marked amount of the typically needed territory of 35,561 species. This adds up to around 64 million square kilometres, which would require various levels of conservation management, from a strict ban on most human activities to regulations on sustainable development.

Scientists have used food puzzles to study how otters learn from each other. Using a combination of puzzle boxes and unfamiliar foods, the team observed that Asian short-clawed otters watched their companions and copied others when they sampled the unfamiliar food. This study aimed to understand how captive release otters would cope with unfamiliar food in their natural environments once they were released. The results suggested that if one otter was given pre-release training, it could pass some of that information onto other otters.

According to a new study, tropical birds may be more colourful than their temperate peers due to the difference in energy availability. Tropical areas have more food year-round and more constant temperatures, potentially allowing tropical birds to evolve more visual signals. Another explication may be diet, as fruits rich in organic pigments, which tend to accumulate in the feathers of birds that consume them, are more abundant in the tropics.

New discoveries

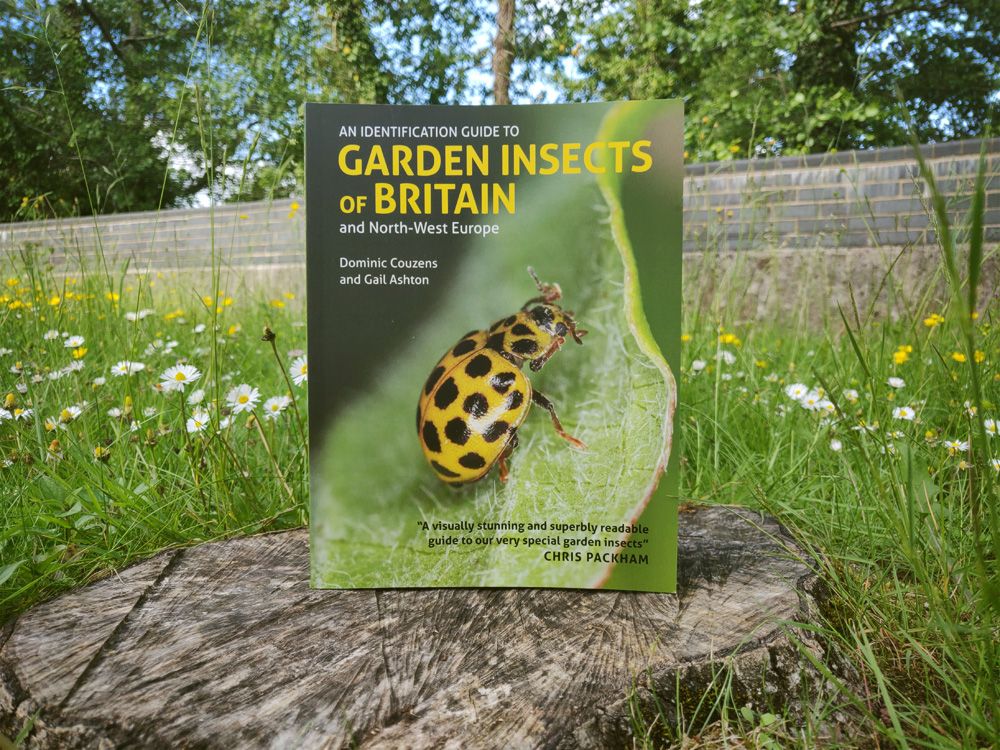

The Critically Endangered adult pine hoverfly (Blera fallax) has been seen in the wild in Britain for the first time in almost a decade. In October 2021 and March 2022, larvae were released at RSPB Abernathy and Forestry and Land Scotland Glenmore, bred as part of the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland’s conservation breeding programme. The pine hoverfly is an important part of forest ecosystems due to its role in both pollination and waste recycling.

A scientist from Newcastle University has rediscovered an ‘extinct’ giant tortoise on Fernandina, one of the Galápagos Islands. Through genetic testing of a female tortoise found in 2019 and a previous specimen found in 1906, the researchers found that the two were genetically linked and distinct from all other living species of Galápagos giant tortoises. Other expeditions to the island have found evidence of at least two or three more tortoises, which are hoped to be of the same species.

Microplastics

Scientists have found microplastics in freshly fallen Antarctic snow for the first time after collecting samples from 19 sites in Antarctica. An average of 29 particles per litre of melted snow was found, consisting of 13 different types of plastics. The most common, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), was found in 79% of samples. This plastic is primarily used in drinks bottles and clothing. While researchers suggested that the most likely source for these airborne microplastics is local scientific research stations, modelling has shown that their origin could be up to 6,000km away.

Researchers in the Canary Islands have discovered a new form of marine pollution that they have termed plastitar, a mix of tar and microplastics. This formation of two contaminants is an unassessed threat to coastal environments and could be leaking toxic chemicals, potentially proving deadly for organisms such as algae. There is concern that this formation may be blocking and inhibiting the development of the ecosystem.

Policy

No-anchor zone in Studland Bay has been extended to save seagrass habitats. The scheme, set up in December, was introduced to stop anchors dropping and damaging the seagrass meadows. However, there is concern that this voluntary scheme is not being advertised enough to sailors and that there are not enough eco-moorings, an alternative to conventional anchors that do not scour the seagrass.