Ducks are waterfowl from the family Anatidae, which also contains geese and swans. They are mostly aquatic birds and there are several resident, breeding and migrant species in the UK. Ducks are split into multiple families, or ‘tribes’, such as dabbling ducks (Anatini), diving ducks (Aythyini) and sea ducks (Mergini). All ducks are generally elongated and broad, with long necks. They have bills and strong, well-developed legs for swimming. The males often have more elaborate plumage than the females, and often similar-looking females of different species can be confused.

Ducks eat a wide variety of food, including vegetation, fish, invertebrates and small amphibians. They have multiple predators including foxes and birds of prey, such as hawks or owls. Ducklings are particularly vulnerable and can also be taken by herons, pike, rats, mink and weasels.

Winter is a great time to birdwatch for ducks in the UK: some species occur in much higher numbers compared to the summer months, and 3 of the 22 species that occur in the UK can only be seen in the winter. The best places to see ducks are lakes, marshlands, estuaries, coastal bays and other wetland areas.

The best equipment for birdwatching is a pair of binoculars or a scope, a notebook and pen to record your sightings, and a guide for more information on other species of duck.

Shelduck (Tadorna tadorna)

Distribution: Present in almost all coastal areas in the UK year-round, as well as some inland waters such as reservoirs.

Size: Length (L): 55–65cm, wingspan (WS): 100–120 cm

Birds of Conservation Concern 4 (BoCC4) Status: Amber

What to look for: Shelducks are a large, boldly-patterned and colourful duck with a white body, dark-green head and red bill, a chestnut band around their chest and pink legs. They can be spotted along estuaries and on the coast.

Eider (Somateria mollissima)

Distribution: During the breeding season, they’re most common northwards from the Northumberland coast and off the west coast of Scotland. During the winter, their range expands to include areas along the east and south coasts, parts of the southwest coast and some areas of the Welsh coast.

Size: L: 60–70cm, WS: 95–105 cm

BoCC4 Status: Amber

What to look for: Eiders are large and impressive sea ducks (rarely seen away from the coast) with distinctive wedge-shaped heads. The males are boldly marked in black and white with subtle green and yellow markings on their head and neck. The females are a dark mottled brown colour all over, providing camouflage during nesting.

Goldeneye (Bucephala clangula)

Distribution: Mainly restricted to the highlands of Scotland during the summer, their winter range includes most coastal areas, lakes, large rivers and other inland water bodies. They are particularly best looked for in north and west Britain.

Size: L: 40–48cm, WS: 77–83cm

BoCC4 Status: Amber

What to look for: Goldeneyes are diving ducks, found mostly in larger lakes and reservoirs. The males are black and white, with a large, dome-shaped head that has a green sheen to it. As its name suggests, it has a distinctive, bright yellow-gold eye, as well as a white spot between its eye and bill. The female is grey with a brown head.

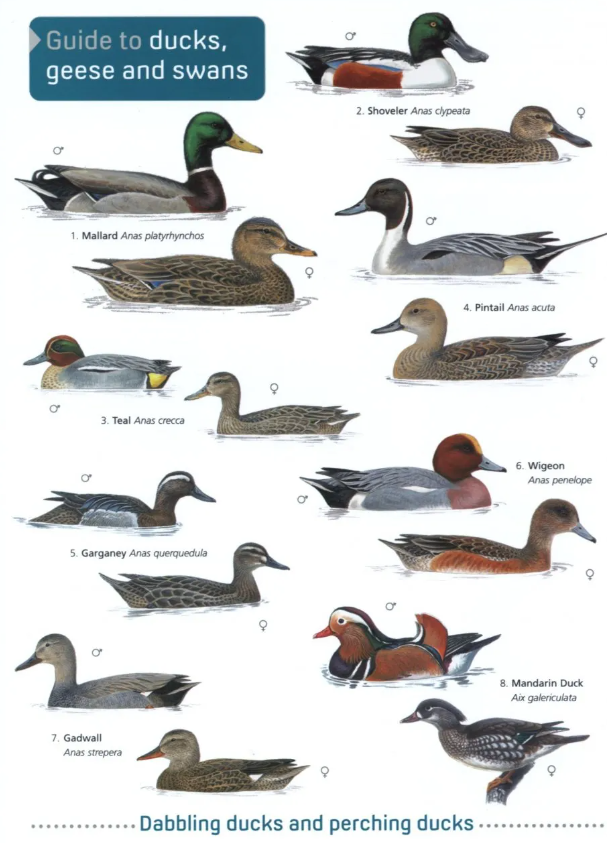

Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)

Distribution: Widespread

Size: L: 55–62cm, WS: 81–98cm

BoCC4 Status: Amber

What to look for: A common species, the male has a bright green, shiny head, yellow bill, and a brown chest. They have a paler underside and maroon and pale wings with a bright blue patch outlined in white and black, called a speculum. The female is a mottled brown, with a brown and yellow bill.

Mandarin Duck (Aix galericulata)

Distribution: An introduced species, the main population is in the south, central and eastern areas of England, but there are small numbers in northern England, Wales and Scotland.

Size: L: 45cm, WS: 65–75cm

BoCC4 Status: Not Assessed

What to look for: The mandarin is an unmistakable bird. The males have a very elaborate plumage of orange, green, blue, white, and brown, with a bright pinkish-red bill. They have plumes on their cheeks, sail-like feathers on their backs and longer feathers down the back of their head. The female is grey and brown, with a white eye stripe and green feathers at the ends of their wings.

Pochard (Aythya ferina)

Distribution: During the summer, pochards are most likely found along the east coast of England but in the winter they can be seen along almost all of the UK coastline, as well as on large lakes and estuaries inland.

Size: L: 44–48cm, WS: 77cm

BoCC4 Status: Red

What to look for: The male pochard has a grey body, black chest and tail, and a reddish-brown head. They have a bright red eye and a black and grey bill. The female is a darker brown, with dark eyes. They also have a black and grey bill, but with less grey than the males. This species was once common but populations are rapidly declining.

Tufted Duck (Aythya fuligula)

Distribution: Widespread across England, parts of Scotland and Northern Ireland. Less common in Wales and south-west England but they can be seen here as their range expands during the winter.

Size: L: 41–45cm, WS: 70cm

BoCC4 Status: Green

What to look for: The male tufted duck is black with white flanks, and a long ‘tuft’ at the black of their head. They have bright yellow eyes and a grey bill with a black spot at the end. The female has brown feathers and no white flanks. The females’ tufts are shorter or sometimes not present.

Gadwall (Anas strepera)

Distribution: Mainly found in the Midlands, south-east of England, parts of Scotland’s east coast, eastern Northern Ireland and along the south and north coasts of Wales. Their range expands during winter to include Cornwall and North Devon, parts of Scotland’s west coast and larger areas of Northern Ireland.

Size: L: 48–54cm, WS: 78–90cm

BoCC4 Status: Amber

What to look for: Male gadwalls are grey-brown in colour, with black and white tail feathers. They have a paler head with a black bill and black eyes. Females are mottled brown, with a black bill edged with orange. They have a white and black speculum that also contains reddish-brown on the males.

Shoveler (Spatula clypeata)

Distribution: Widespread in England and along the Welsh coast during winter but more restricted to east and north-east England and the Midlands during summer, with some populations in parts of Scotland, Northern Ireland and the south coast of England.

Size: L: 47–53cm, WS: 77cm

BoCC4 Status: Amber

What to look for: The shoveler has a large, broad shovel-like bill. The male has a dark green head, white chest, reddish-orange flanks, and a black and green back and tail. The males also have yellow eyes and a black bill. The female is a mottled brown, with a yellow-orange bill.

Pintail (Anas acuta)

Distribution: Restricted to scattered areas of Scotland and the east of England in summer in only small numbers. Their significant winter population has an expanded range that includes much of the English coastline and parts of Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland.

Size: L: 55–65cm, WS: 80–95cm

BoCC4 Status: Amber

What to look for: This is an uncommon species in the UK, but it is easily distinguishable by its long tail feathers. The male has a dark chestnut head, a white chest with black feathers on the back of its neck, and a grey body. They have black feathers along their back and a black tail, dark eyes, and a grey and black bill. The female has shorter tail feathers, a mottled brown colouration and a grey bill.

Useful Resources

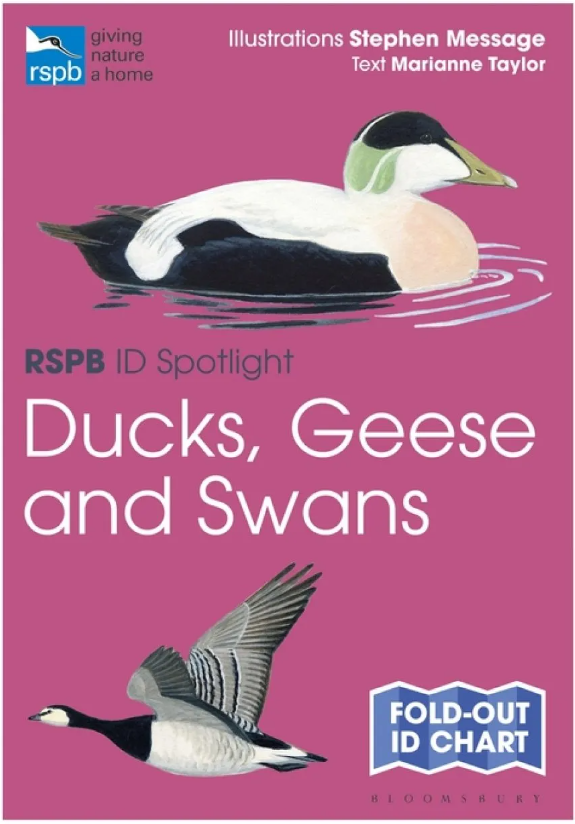

RSPB ID Spotlight: Ducks, Geese and Swans Unbound | June 2022

RSPB ID Spotlight: Ducks, Geese and Swans Unbound | June 2022

This guide is a reliable fold-out chart with illustrations of 30 of the UK’s most familiar wildfowl by renowned artist Stephen Message. Species are grouped by family to assist with identification and artworks are shown side-by-side for quick comparison. The reverse of the chart details the habitats, behaviour, life cycles and diets of the group, as well as the conservation issues they are facing and how the RSPB is working to support them.

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans Unbound | January 2019

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans Unbound | January 2019

This fold-out chart from the Field Studies Council (FSC) shows 32 species of ducks, geese and swans you are likely to see in Great Britain and Ireland. Not included are domestic ducks and geese descended from respectively the mallard (1 species) and the greylag (30 species).

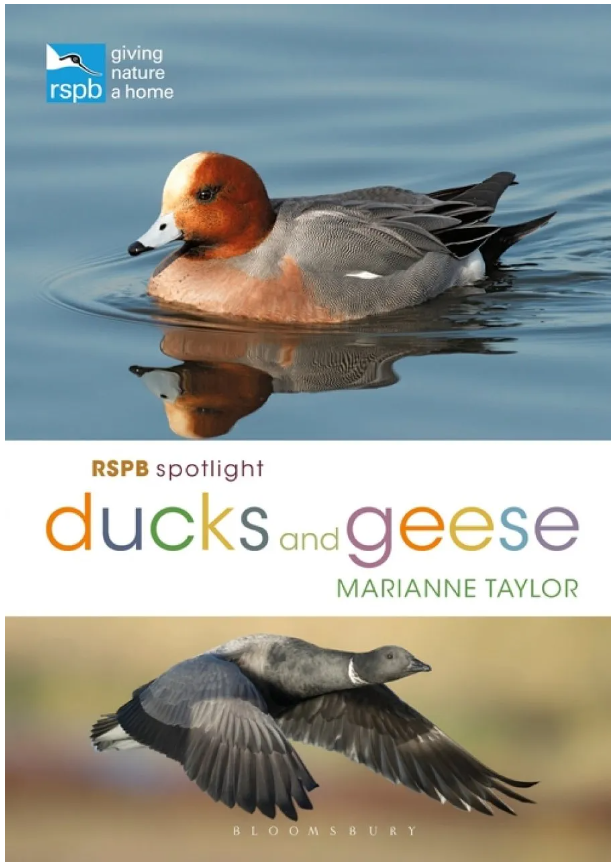

RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese Paperback | May 2020

RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese Paperback | May 2020

This detailed ‘biography’ of ducks and geese in the UK covers 30 species in total. It includes chapters on their evolution, anatomy, courtship displays and breeding behaviour. The author reveals their migrations and examines their social interactions with their own and other species, including humans, and discusses their presence in historical folklore and literature.