Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of Fourfields, The Running Sky and Landfill. His latest book, Greenery, is a poetic hymn to spring time, a masterpiece of nature writing that is deeply informed and profoundly beautiful.

Tim Dee is a naturalist, radio producer, and author of Fourfields, The Running Sky and Landfill. His latest book, Greenery, is a poetic hymn to spring time, a masterpiece of nature writing that is deeply informed and profoundly beautiful.

Between the winter and the summer solstice in Europe, spring moves north at about the speed of swallow flight. That is also close to human walking pace. In the light of these happy coincidences, Greenery recounts how Tim Dee travels with the season and its migratory birds, out of Africa from their wintering quarters in South Africa, through their staging places in Chad and Ethiopia, across the colossal and incomprehensible Sahara, and on into Europe. Tim Dee has answered questions about this remarkable journey.

For those who don’t know, you have published three other major titles on green spaces and birds- Landfill, The Running Sky, and Four Fields. Following from these, how did the idea to travel with spring and its migratory birds come about? And how does Greenery differ from your previous books?

For those who don’t know, you have published three other major titles on green spaces and birds- Landfill, The Running Sky, and Four Fields. Following from these, how did the idea to travel with spring and its migratory birds come about? And how does Greenery differ from your previous books?

My last book was Landfill, a sort of junkyard travel-guide to the gulls that now thrive on our waste and in the middle of our towns and cities. Inevitably it was dirty and messy and botched: modern nature is like that. It has to find ways and means to live alongside us – we who are the most-botched species of all. I admire the gulls and I was fascinated by the gullers – watchers of gulls – who spend time in wretched places like landfill sites in order to connect with their quarry, but afterwards I needed some fresher air to live in and some wilder life to watch, and so the spring, which has always been my favoured season, appealed, and most especially some witnessing of the movement of passage migrant birds that make the European spring for birdwatchers. When I discovered that spring moves north through Europe at somewhere between the speed a swallows flies at and the speed we might walk at (about 4 km an hour), I knew that I had to try to follow the birds and the season for as long and as far as I could. So, I start with barn swallows in the European midwinter in midsummer South Africa and I end with the same species, who knows perhaps even the same individuals, in midsummer arctic Norway. Who wouldn’t want to have as much spring as possible?

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?

By travelling north you poetically write about the birds that come and go; from observing redstarts in Lake Lagano, Ethiopia, to enjoying the dawn chorus in a reedbed in Somerset. What can be learned from birds in migration, and how is migration changing for them?

Studying and thinking about migration tugs at our notions of home. Migratory animals carry their homes with them. Yet, when I first saw barn swallows in South Africa I couldn’t see them as anything but away from their home. In fact, of course, they were perfectly at home: they were meant to be there and able to be fully alive there. Ever since migration has been observed, birdwatchers have ceaselessly wondered where the birds have come from, where they are going, how they know where to go and how they know how to live at the other end of the world. Migration has always intrigued – Homer makes poetry from it, Aristotle discusses it, the Bible and the Koran make parables for life from it. Nowadays we know more and more of its facts – know for example that a migrant redstart may literally return to the same tree in sub-Saharan Africa in its wintertime just as it flies to the same oak in a wooded coombe in Exmoor every spring of its life; but we also begin to understand (and face up to) how much our activities are tugging at the world’s time and making migration and a bird’s swapping of one tree for another harder and harder. This is what phenological mismatch is all about: the unseasonal time that our activities are creating.

You explore time and movement in this book. In a very fast-paced world, where few have the time to slow down and connect to the seasons, how has journeying with spring changed you? Was there anything specific you were looking for and anything you found?

To try to have more spring has been my mantra, to go looking for signs of new life even before a calendar year has ended, like a mistle thrush singing in November and thereby meaning therefore to have spring again, or rooks visiting their old nests each day from the autumn onwards with a literal view to their future; and to travel when possible both south from Britain to Mediterranean Europe where spring arrives earlier and then north towards the Arctic Europe where spring lasts longer. Hearing a pied flycatcher still singing in northern Norway when the same species are silent in their British breeding woods feels like a life-bonus, feels like more of life, which can only be good. We are only given one springtime in our own lives but the return of the season and the cyclical round or rondure of the natural year is a marvellous tonic and corrective to the linearity of our one-direction journey. Again, who would say no to that – to a bit of time travel and season stretch in order to stay with the season of becoming and of re-energy. Greenery is an anagram of re-energy: I was thrilled to discover that.

When most people think of spring they think of new life, new beginnings, however you eloquently write “spring means more to me with every year that passes and takes me deeper into my own autumn.” Could you elaborate more on this, what does springtime mean to you?

There’s that lyric to a song: you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til its gone…. And I think as we get older the morning of life, the world’s morning as D H Lawrence called spring, feels more and more poignant and uplifting. We are headed only one way but, hey presto, here are new shoots, and green beginnings once more, and then a chiffchaff, fetching an echo out of a wood, as Gilbert White noticed them doing in Eighteenth Century Selborne in Hampshire. My eyesight has got worse, my hearing is half-baffled, I move increasingly with a wobble, but the injection of new birds from the south, the heavenly racket of their song, and seeing them at home in their new places is a forever tonic, like an effervescing vitamin C tablet, or a pick-me-up, or a fillip – life is worth living among those that are living it most, and spring visiting birds are the most alive – active, mobile, purposeful, committed – things that I know.

As you explore life and death, love and grief through springtime, is there anything in particular you would like for people to take away from this book?

I think we all spend a lot of time ignoring time, shut away from the weather, heating our lives, conditioning our air, eating strawberries out of season, yet I know that we all, almost all of us at least, notice the spring, want it, anticipate it, lift our faces to the first splash of sun after grey skies, talk about snowdrops, look out for the first swifts, and so on… We are reminded of spring by spring itself coming around, it schools us in life and growth, in beginnings and becomings; and in my book I just want to underline that reminder and encourage us all to take in what can be taken in, and to keep in step with the passing of time and so live happily in time and on time too. Look at the birds that do that so well; I have done that and it has helped me live.

Tim Dee has been a birdwatcher for most of his life and written about them for twenty years. As well as Greenery, he is the author of Landfill, The Running Sky and Four Fields and is the editor of Ground Works.

Hardback | Oct 2018 | ISBN-13: 9781908213624 £15.99 £18.99

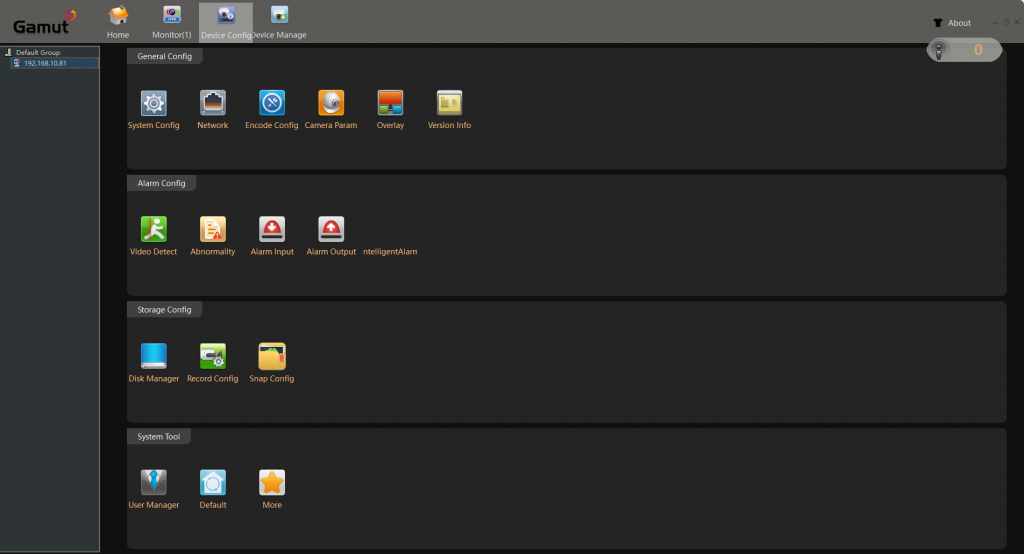

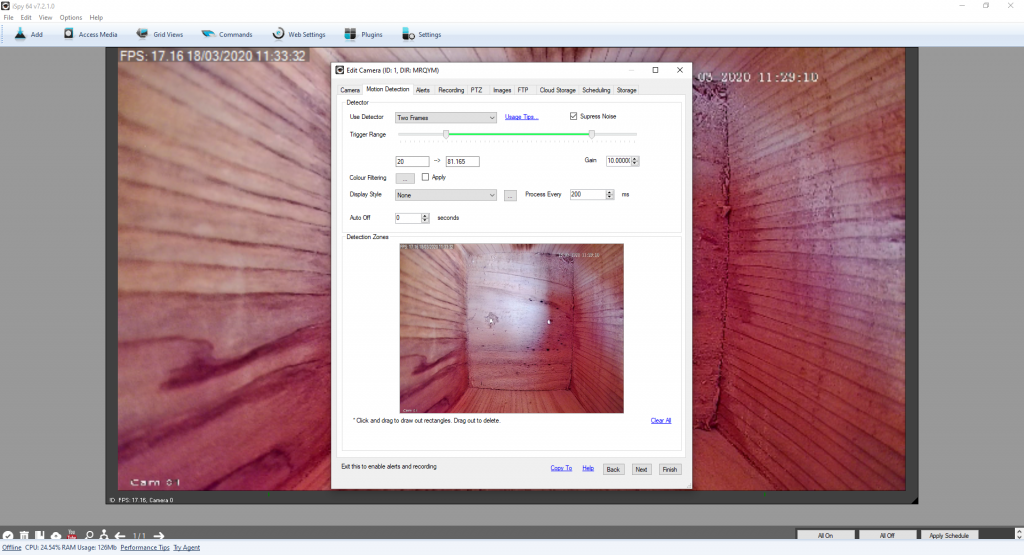

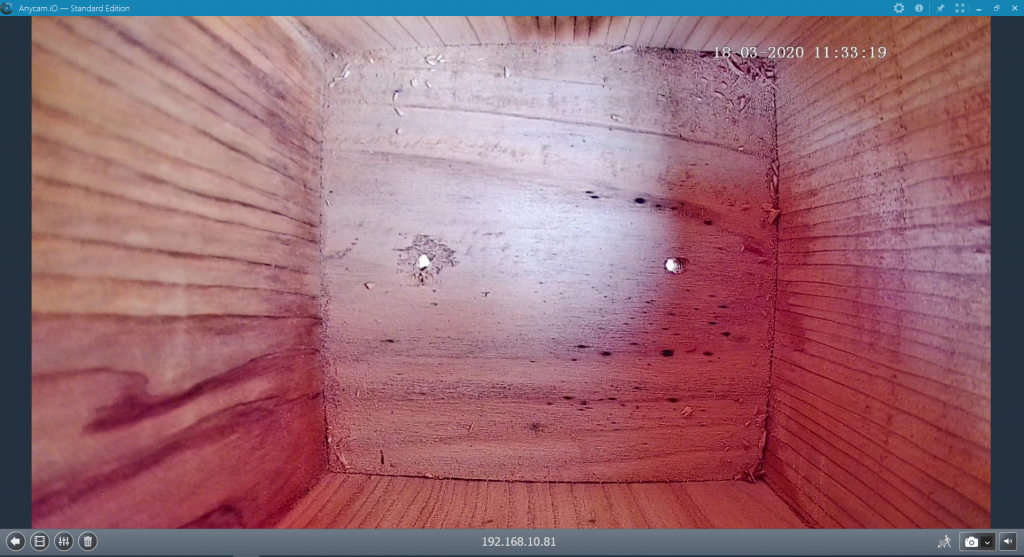

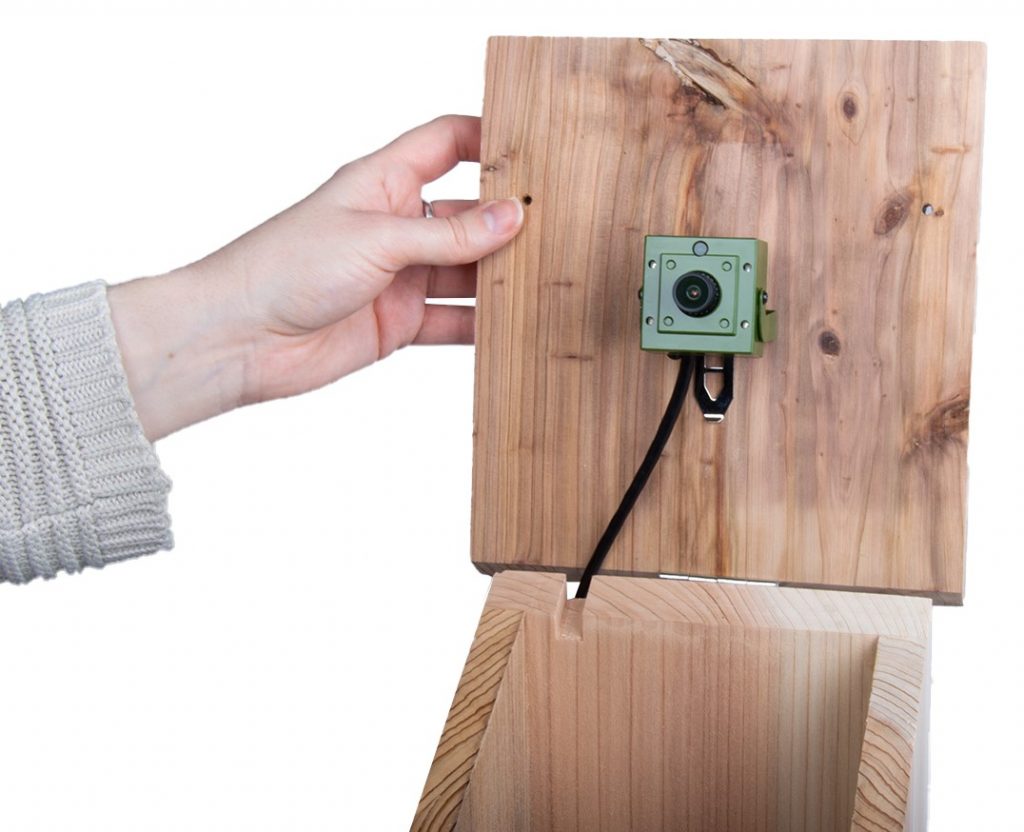

After the box was installed in position, we connected everything up and downloaded software to connect to the camera. We have tried three software programs, all of which are free to download, although additional features may require payment.

After the box was installed in position, we connected everything up and downloaded software to connect to the camera. We have tried three software programs, all of which are free to download, although additional features may require payment.

wanting to live in gardens?

wanting to live in gardens?

To get to know Stephen Rutt and his new book, we asked him a few questions on his inspiration, advice and some interesting facts he’s discovered on his journey while writing

To get to know Stephen Rutt and his new book, we asked him a few questions on his inspiration, advice and some interesting facts he’s discovered on his journey while writing

Gulls have proved to be adaptable, especially regarding human interaction; what changes have they already accomplished and what do you envisage for them in the next fifty or even one hundred years?

Gulls have proved to be adaptable, especially regarding human interaction; what changes have they already accomplished and what do you envisage for them in the next fifty or even one hundred years?