The noise that a hedgehog makes when crunching dried cat food is surprisingly loud… and when you have two or three sharing the same plate, as I sometimes do, they produce quite a din! Such a din in fact that I can hear their munching and squabbling from my bedroom window – even with the windows shut. But what a satisfying racket! It is a real privilege and a delight to have hedgehogs using your garden. By feeding them and making your garden hedgehog friendly you can take comfort in the knowledge that you are doing your bit to help these beleaguered animals.

In the 1950s, there were possibly as many as 30 million hedgehogs living in the UK, but today there could be as few as 522,000 – that’s a reduction of 97%. Suggestions as to why the population of these enchanting animals has taken such a nose dive include: the intensification of agriculture and the loss of hedgerows (which are important wildlife corridors), the alarming decline of the invertebrates on which hedgehogs feed (almost certainly due to the use of pesticides) and another, perhaps surprising factor, is predation by badgers. It turns out that wherever badgers thrive hedgehogs struggle, especially in areas where there is limited cover. Moreover, we are sadly all too familiar with the sight of squashed hedgehogs on our roads and it is thought that many thousands meet their end in this way each year. Although hedgehogs are very urbanised, their road safety skills remain poor!

Hedgehogs are also struggling with the current trends of homeowners who are turning their gardens into “garden rooms”. By covering our gardens in decking, patio, artificial lawn or tarmac we are reducing their wildlife value including foraging opportunities for the hedgehog. The erection of impenetrable garden fencing only adds to the problem because it does not permit egress from garden to garden. Hedgehogs may roam about 2km and visit up to 20 gardens every night to seek out food sources. Although surveys suggest that urban hedgehogs might actually be doing better than their rural cousins – these current gardening fashions are not doing anything to promote their cause. Our most popular mammal favours an untidy garden with fences full of holes.

So, what can we do to help the hedgehog? As I write this blog we are marching through autumn, but hedgehogs are still out and about, trying to put on weight for hibernation. November 5th is approaching and this is a dangerous time for hedgehogs as they often seek shelter within bonfire piles, so please check for hedgehogs before setting yours alight.

You and your garden can become hedgehog friendly by just providing some or all of the following:

- Make sure that hedgehogs can gain access in and out of the garden. Holes in fences only need to be 13cm square and they will soon be found and used on a regular basis. If you want to neaten off the hole, then consider the Eco Hedgehog Hole Fence Plate which is made from 100% recycled plastic and available at NHBS.

- Include compost heaps and overgrown areas in your garden as these are a great source of invertebrate prey

- Do not use slug pellets and pesticides in your garden.

- Provide a water source for hedgehogs such as a pond with a gently sloping edge, or a simple bowl

Hedgehog House - Provide areas where hedgehogs can spend the daylight hours, hibernate and even produce their young. This can be a simple wood or leaf pile, or if you prefer you could purchase a hedgehog house or shelter of which there is a large range of choices within our catalogue and on the website

- Make hedgehogs safe; as well as checking your bonfire piles, be careful with the use of lawn mowers and strimmers and make sure that netting cannot cause entanglement – for example, the bottom edge of fruit netting can be raised from ground level.

Of course, hedgehogs also appreciate some help in food sourcing and are quick to make use of our generosity. Feeding becomes particularly important in periods of pro-longed dry weather (such as we had this year) when soft-bodied invertebrates like slugs, snails and earthworms are less likely to be at large. It is also important to put out food towards the end of summer and beginning of Autumn when late born hoglets need all the help they can get in putting on enough fat to sustain them through the winter months. It is worth remembering that a hedgehog needs to weigh about 600g at the start of the hibernation period in order to survive until the following Spring.

Feed hedgehogs on wet or dry cat food and this can be supplemented with items like sunflower seeds, nuts and live or dried mealworms (Please feed these in moderation to ensure a balanced diet). There are also proprietary brands of hedgehog food available which provide a good balance of the nutrients that they need. But never put out bread and milk! Hedgehogs are intolerant to lactose and bread doesn’t provide the nutrition they need.

Put the food out in a bowl or saucer in the same place every night and hedgehogs will soon learn where it is located. Of course, this food may also be found by neighbourhood cats and foxes, so you could try to protect the food by placing it within a shelter.

It is great fun to put out a trail camera positioned near the food source so that you can obtain images and videos of your garden visitors – this is how I discovered that at least three visited my garden!

As winter sets in be on the lookout for hedgehogs that are out and about in daylight. An animal that is showing this unusual behaviour is likely to be a late autumn born youngster and probably starving. These animals need help and should be taken in and fed. It is best to contact your local wildlife hospital or rehabilitation centre for advice in this situation.

Hedgehogs are fantastic little mammals whose ancestors first appeared on this planet at least 52 million years ago. By giving some thought to the ones in your garden you can take comfort in the fact that you are contributing to their continued survival. It is very rewarding to have hedgehogs in your garden and certainly worthwhile putting up with their noisy nocturnal snacking.

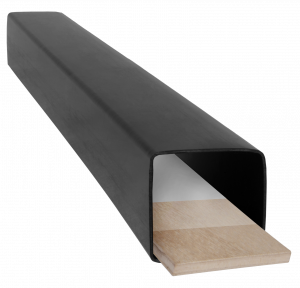

Dormouse Footprint Tunnels

Dormouse Footprint Tunnels

Live Trapping of Small Mammals

Live Trapping of Small Mammals

Our trap has a few innovative features designed to make assembly and disassembly easier. Firstly the strings are wrapped around a winding mechanism which greatly reduces the stress and time-consuming act of sorting through tangled lines in the dark.

Our trap has a few innovative features designed to make assembly and disassembly easier. Firstly the strings are wrapped around a winding mechanism which greatly reduces the stress and time-consuming act of sorting through tangled lines in the dark.

The

The  The

The  The

The

Perhaps the simplest survey technique to determine dormouse presence is searching for the nest box residents.

Perhaps the simplest survey technique to determine dormouse presence is searching for the nest box residents.

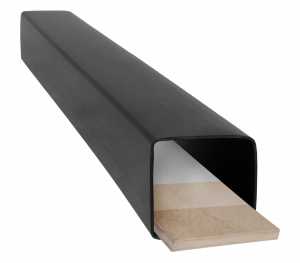

It is a non-invasive survey technique, which does not require a licence as the chance of disturbing dormice is very low. The 40cm tube, houses a wooden platform which contains the charcoal ink and paper on which footprints are left. Compared with nest tube surveys, footprint tunnels can reduce the survey period required and provide an indication of the presence or likely absence of dormice at a site.

It is a non-invasive survey technique, which does not require a licence as the chance of disturbing dormice is very low. The 40cm tube, houses a wooden platform which contains the charcoal ink and paper on which footprints are left. Compared with nest tube surveys, footprint tunnels can reduce the survey period required and provide an indication of the presence or likely absence of dormice at a site.