There are over 650 species of spider within the UK, and although many may find spiders unappealing or even frightening, they are fascinating in their own right. While many spiders are present throughout the year, autumn is the best time to see them outdoors.

Identifying spiders can often be difficult, as they are very small, elusive, and many species resemble one another. The colouration and pattern of a spider can be a useful way to identify them, as well as other key features such as the structure of their webs. In some cases, it is necessary to take a closer look at the genitalia under a microscope, as this can be the only way to confidently identify certain species. You can also use your location as a clue, as some species are more likely to be found in certain parts of the UK.

To survey for spiders, you can search by eye or you can use equipment such as a sweep net or a sampling tray, and a hand lens can help you pick out features on smaller species. There are also lots of field guides and books available for more information on different types of spiders.

In this article, we’ll show you several fairly common species that you may find in your garden or local green space.

Garden Spider or Cross Orbweaver (Araneus diadematus)

Distribution: Common and widespread

What to look for: These spiders are greyish-brown or reddish-brown with a white pattern across their back that resembles a cross. They can also sometimes be bright orange. They have striped legs, and females are twice the size of males.

Noble False Widow (Steatoda nobilis)

Distribution: Widespread across southern England, with their range increasing northwards

What to look for: This species can be confused with many other UK species. Their body is dark brown, with variable patterns on their abdomen. Usually cream and dark brown marks that can sometimes resemble a skull.

Did you know? This is a non-native species in the UK and was thought to be introduced in the late 1800s. Despite many rumours, bites from this species are rare, usually occurring when the spider is disturbed. The bites have been compared to a wasp sting, however guidance should be sort if you are concerned about a bite.

Common Candy-Striped Spider (Enoplognatha ovata)

Distribution: Occurs throughout the UK

What to look for: The common candy-striped spider has several colour variations. Their abdomen usually has a pale creamish-white background. The pattern on it can be bright pinkish-purple in a V shape pointing towards the head, a solid pinkish-purple triangle, black lines that can be either thick or thin, or a variation of black marks and spots. Their cephalothorax (fused head and thorax) is a pale yellow colour, with a dark line down the middle, and their legs are also a similar pale yellow. In the field, it is incredibly difficult to distinguish this species from a similar species, the scarce candy-striped spider (Enoplognatha latimana). Confirmation of the species usually requires examination under a microscope.

Goldenrod (Flower) Crab Spider (Misumena vatia)

Distribution: Common in southern UK

What to look for: The goldenrod crab spider has some colour variation, appearing white, yellow or green, They often have red lines on either side of their abdomen. Their abdomen is bulbous and their front legs have a crab-like appearance, hence their name. The female is much larger than the male.

Did you know? This species can change its body colour to match its background! It takes a few days to occur, but it helps to disguise the spider as they sit and wait for their prey to land near them.

Zebra Jumping Spider (Salticus scenicus)

Distribution: Widespread

What to look for: The zebra jumping spider can grow up to 8mm, which is surprisingly large for a jumping spider, and they can jump an impressive 10cm. As their name suggests, they have a black and white striped pattern, but it can be hard to tell them apart from similar species of jumping spider. They are usually found on walls, rocks, or tree trunks.

Cucumber Green Spider (Araniella cucurbitina)

Distribution: Occur throughout the UK

What to look for: Around 4-6mm long, this small spider has a bright yellowish-green abdomen and a pinkish cephalothorax. They also have small black spots along their abdomen. They are very similar to another cucumber spider A. opisthographa, but it can be difficult to tell them apart in the field.

Labyrinth Spider (Agelena labyrinthica)

Distribution: Widespread in southern England, as well as in Wales

What to look for: The labyrinth spider can grow quite large, up to 18mm long. They create long, funnel-shaped webs in long grass and hedgerows. Their abdomen has a pale brown stripe with darker bands on either side, and these bands have several paler chevron markings through them. Their cephalothorax also has a pale brown stripe, with an orange-brown band on either side, and their legs are orange-brown with paler hairs.

Nursery Web Spider (Pisaura mirabilis)

Distribution: Widespread across most of the UK, although less frequent in the north

What to look for: The nursery web spider is quite variable in colour, and can have a grey, dark brown, or yellow-orange body. They have a slender, pointed abdomen, with two dark brown lines running from the spinnerets (silk-spinning organs) all the way to the front of the cephalothorax. They also have pale tear-shaped marks next to their eyes.

Useful books and equipment

Britain’s Spiders: A Field Guide

Britain’s Spiders: A Field Guide

Now in a comprehensively revised and updated new edition, Britain’s Spiders is a guide to all 38 British families, focussing on spiders that can be identified in the field. Illustrated with photographs, it is designed to be accessible to a wide audience, including those new to spider identification.

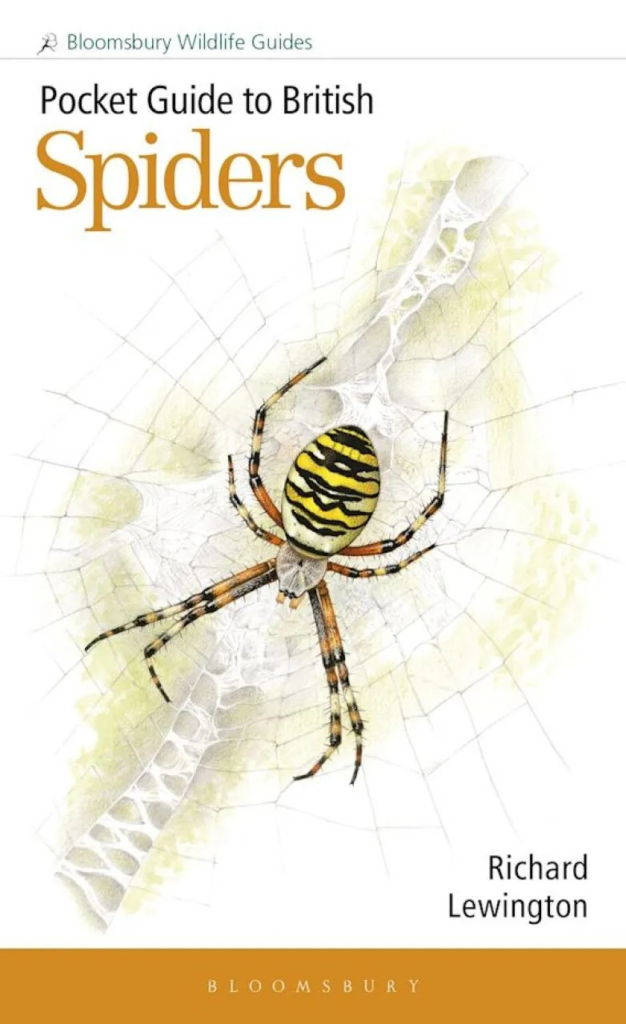

Pocket Guide to British Spiders

Featuring 130 of the most common and readily identifiable species, this illustrated pocket book is the ideal comparison for anyone interested in the naturally occurring spiders found in the British Isles.

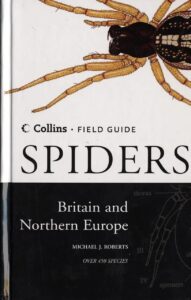

Collins Field Guide to the Spiders of Britain and Northern Europe

This major identification guide to 450 species of spider is designed for easy use. Each species is described in detail and illustrated in colour, including common colour variants and differences between the sexes.

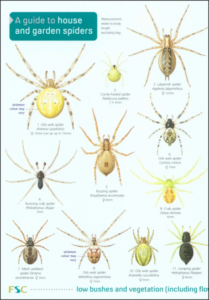

A Guide to House and Garden Spiders

Of the 33 spider families represented in Britain, 21 are featured in this chart. The guide includes colour illustrations and a table with identification features, habitat and methods of prey capture for the 40 spiders featured in the chart.

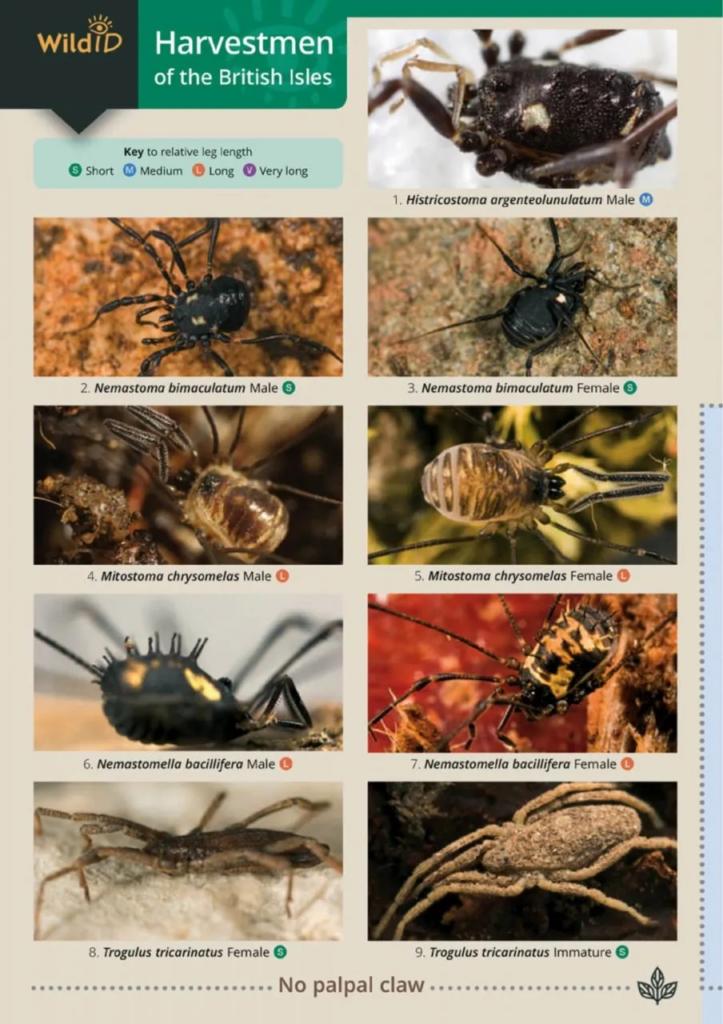

Harvestman of the British Isles

A fully up to date second edition, covering all 34 species that have been recorded in the wild in Britain and Ireland. There are photographs of each species, with separate photos for males and females, and a comprehensive identification table.

A clear plastic pot with a snap on magnifying lid with x3.5 magnification, ideal for viewing pond life and terrestrial invertebrates up close.

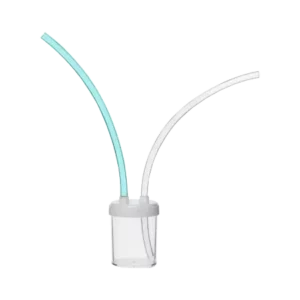

The pooter is a classic piece of entomological equipment, enabling the capture of small or delicate invertebrates without the risk of damaging them or losing them in the undergrowth. It consists of a transparent plastic collecting jar with a lid containing two holes, one of which has a fine mesh covering.

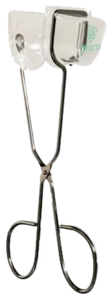

These scissor action Bug Tongs are the perfect way for children to collect larger insects and bugs which cannot easily be caught using a pooter.

Opticron Hand Lens 23mm 10x Magnification

Opticron Hand Lens 23mm 10x Magnification

This Opticron Hand Lens contains a high quality 23mm doublet lens, made of glass and provides excellent distortion-free magnification. The 10x magnification is recommended for general observations and this magnifier is the one most commonly recommended for all types of fieldwork.

Bumblebees: An Introduction

Bumblebees: An Introduction