Mustelids are species in the family Mustelidae of the order Carnivora. They are medium to small mammals comprising around 56-60 species worldwide, eight of which are found in the UK, including feral ferrets. While the conservation status of most is considered Least Concern in Great Britain, several of these species are considered Critically Endangered or Near-Threatened in individual UK countries. This is mainly due to historical and current persecution and habitat loss. Pollution, however, has also impacted mustelid species, such as the otter, which was particularly affected by pesticides, such as organochlorines. Thankfully, many of the most harmful pesticides have been banned in most European countries since 1979, allowing populations to begin to recover. Other conservation efforts, such as legislative protection, habitat restoration and relocations, are also helping to restore mustelid populations.

Mustelids, other than badgers, are characterised by their long, thin body shape, which allows them to enter burrows and tunnels used by their prey. These mainly include rabbits and small mammals, but also some birds, bird eggs, invertebrates and fish. Several species resemble one another, particularly the stoat and the weasel, but several key identification features can help you to correctly identify the species. Colouration, body size and distribution within the UK can be helpful, as well as other features such as tail size, shape and colour, snout shape and even their running gait. Binoculars or a scope can help you to identify these features from a distance.

Polecat (Mustela putorius)

Distribution: Found throughout Wales, parts of Scotland and central and southern England.

Body length: 32–45cm

Tail length: 12–19cm

What to look for: This species has dark brown guard hairs, the top or outer layer of the coat, and buff-coloured underfur, giving them a two-tone appearance. They have a dark face with a white stripe across it, similar to a ferret. They can produce hybrid offspring with ferrets that can be difficult to identify, but the hybrids usually have a lighter appearance and more white on their faces.

Pine Marten (Martes martes)

Distribution: Mainly found in Scotland and Ireland, although fragmented populations are found in northern England and North Wales.

Body length: 46–54cm

Tail length: 18–27cm

What to look for: The pine marten has a chestnut-brown colouration with a pale yellow patch on its chin and throat that resembles a bib and a long, bushy tail. The ‘bib’ is uniquely shaped on each pine marten, meaning individuals can be identified by the pattern.

Stoat (Mustela erminea)

Distribution: Widespread throughout the UK, although absent on the Isles of Scilly, most of the Channel Islands and some Scottish islands.

Body length: 17–32.5cm

Tail length: 6.5–12cm

What to look for: This species is orangy-brown with a cream-coloured underside and throat. They have a very similar appearance to the weasel but there are some key differences: the stoat is larger, with a longer, black-tipped tail and a distinctive bounding gait compared to the run of the weasel.

Weasel (Mustela nivalis)

Distribution: Widespread in England, Wales and Scotland but is absent from Ireland and most islands.

Body length: 11.4–26cm

Tail length: 1.2–8.7cm

What to look for: The weasel is the smallest species of Carnivora in the UK, with a russet-brown coat that can appear more orange in certain lights, and a cream underside and throat. Their tails have no black tip and are much shorter compared to the stoat’s tail, and they run with a straight back, rather than the arched, bounding gait of the stoat.

American Mink (Neovison vision)

Distribution: Widespread across the UK, thought to be absent from the far north of Scotland and some Scottish Islands.

Body length: 31–45cm

Tail length: 13–23cm

What to look for: The mink has dark brown fur with a white chin and throat and a narrow snout. They can resemble otters but they can be distinguished by their smaller size and face, as well as their darker fur.

Did you know? The American mink is an invasive species, introduced into the wild in the 1950s and 1960s as a result of fur farm escapees and deliberate releases. Accurate population estimates are difficult but many areas are attempting to control numbers as American mink are a serious threat to the endangered water vole (Arvicola amphibius).

Eurasian Otter (Lutra lutra)

Distribution: Rare but widespread throughout the country, although absent from areas in central and southern England, the Isles of Scilly, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.

Body length: 60–80cm

Tail length: 32–56cm

What to look for: This species has brown fur with a grey tint, a paler chest and throat and a broad snout, which can be used to distinguish it from the mink.

Did you know? In the UK, otter populations were in severe decline in the second half of the 20th century, due to hunting, pollution from pesticides and habitat loss. Conservation efforts have allowed populations to start to recover, with otters returning to every county in England.

European Badger (Meles meles)

Distribution: Widespread throughout England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Absent from far north Scotland, Scottish Islands, the Isles of Scilly, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands.

Body length: 75–100cm

Tail length: 15cm

What to look for: This is a distinctive species, with a grey back, black underside and paws, a fluffy, short tail and an unmistakable black-and-white striped face.

(Feral) Ferret (Mustela furo)

Distribution: Feral populations throughout Britain, but thought to survive best on offshore islands, such as Shetland, Mull, Harris, Islay, Rathlin Island and North and South Uist. There is also a population in North Monaghan.

Length: 48–56cm (including tail)

What to look for: This species has multiple colour variations, including white, brown, black or mixed fur. Their nose is usually pink, although they can have darker blotches, and they have a thin white band across the face with darker eyes, giving it a bandit-like appearance. They can be hard to distinguish from the polecat, from which it is descended. Where there is an established population of both species, hybridisation can occur. Patches of white on the fur, particularly the paws, can indicate either a ferret or a hybrid.

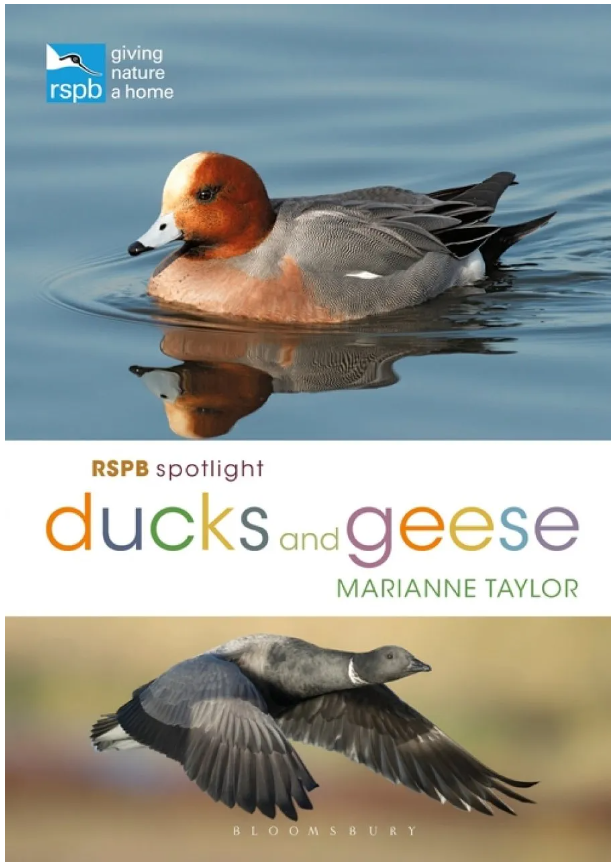

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans

Guide to Ducks, Geese and Swans  RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese

RSPB Spotlight: Ducks and Geese