The UK is home to seven native species of amphibian. Over the winter, these frogs, toads and newts have all been hibernating, but it will soon be time for them to venture out to their breeding ponds and pools. If you’re lucky, you will be able to spot them when you’re out and about.

In this blogpost we will provide you with some of the key characteristics of each species which will help you to identify exactly what you’re looking at. For those of you who are keen to find out more, we have also provided a list of field and identification guides at the bottom of the page.

Newts

Newts are members of the salamander family and have a lizard-like body shape. They are semi-aquatic, spending part of the year on land, returning to the water in spring to breed. Eggs are laid in the water where they hatch into tadpoles and then proceed to develop front and back legs, along with gills for breathing. They leave the water in late summer once their gills have been lost.

The three species of newt which are native to the UK are the Smooth Newt (Lissotriton vulgaris), the Palmate Newt (Lissotriton helveticus) and the Great Crested Newt (Triturus cristatus).

Smooth Newt:

• Size: Grows to around 10-11cm in length.

• Colour: Males brown/olive; females light brown. Belly is usually yellowy orange with black spots. The throat is pale with darker spots.

• Skin Texture: Smooth

• Habitat: Spring to early summer in ponds and pools (frequently found in garden ponds). Late summer under logs and stones near to water.

• Other notes: The male has a wavy back crest during the breeding season.

Palmate Newt:

• Size: Grows to around 7-11cm; slightly smaller than the smooth newt.

• Colour: Males olive brown; females yellowish brown. The throat is white/pale pink and does not have spots or speckling. The eye has a dark stripe running horizontally through it.

• Skin Texture: Smooth

• Habitat: During the breeding season (early March to late May) in shallow ponds, often in heathland bogs. During summer in woodland, ditches and gardens near to water.

• Other notes: During the breeding season, the male palmate newt has a ridge running along its back and a tail which ends in a filament. Its back feet are also webbed.

Great Crested Newt

• Size: Up to 15cm in length. Females may be even larger than this.

• Colour: Dark brown or black with white/silver dots on sides. Underside is orange with black spots. Pale throat.

• Skin Texture: Warty

• Habitat: March to May in deep ponds with vegetation. Great crested newts often range further than smooth or palmate newts during the summer and can be found in gardens, ditches and woodland.

• Other notes: The male has a very distinctive crest during the breeding season which is broken at the point where the tail meets the body. The crest also has a silver stripe.

Frogs

Frogs are short-bodied, tailless amphibians that largely lay their eggs in water. These eggs hatch into aquatic larvae, known as tadpoles, before metamorphosing into froglets and then adults.

There are two native species of frog in the UK: the Common Frog (Rana temporaria) and the Pool Frog (Pelophylax lessonae).

Common Frog

• Size: Adults grow to 6-9cm in length.

• Colour: Olive green to yellow-brown. Usually spotty or stripy with dark patches behind the eyes and darker barring on hind legs.

• Skin Texture: Smooth and moist.

• Habitat: From late February to early October in all sorts of ponds and pools. Common in gardens.

• Other notes: Moves by hopping. Common frogspawn is gelatinous with black embryos and tadpoles are initially black but turn speckled brown. (This is a useful way of distinguishing them from toad tadpoles, which remain dark until development).

Pool Frog

• Size: Adults grow to 6-9cm in length.

• Colour: Usually brown with dark spots. Light yellow back stripe.

• Skin Texture: Smooth and moist.

• Habitat: Currently only present in localised spots in East Anglia.

• Other notes: Males have prominent vocal sacks on the side of the mouth.

Toads

Toads are characterised by dry-looking, warty skin and short legs. They usually move via a lumbering walk, as opposed to the hopping motion used by frogs. As with frogs, most toads lay their eggs in water. These hatch into tadpoles before growing legs and metamorphosing into the adult form.

Within the UK there are two native species of toad: the Common Toad (Bufo bufo) and the Natterjack Toad (Epidalea calamita).

Common Toad

• Size: Females grow up to 13cm whilst males are smaller and usually reach only 8cm.

• Colour: Brown to grey-green. Paler on the underside.

• Skin Texture: Dry-looking and warty.

• Habitat: From late February in damp, shady spots near to breeding ponds. During the summer in woodlands, gardens and fields.

• Other notes: The common toad has amber eyes with a horizontal pupil. Moves with a lumbering walk or small hop. Eggs are laid in strings in a double row. Upon hatching the tadpoles are dark and, unlike frog tadpoles, remain so until they develop.

Natterjack Toad

• Size: Females grow up to 8cm whilst males are slightly smaller.

• Colour: Pale brown/green, often with brightly coloured red or yellow warts. Yellow stripe down the spine.

• Skin Texture: Dry-looking and warty.

• Habitat: Coastal dunes and lowland heath, often in open, unshaded habitats. The natterjack toad is very rare in the UK.

• Other notes: The natterjack toad has amber eyes with a horizontal pupil. Moves with a running motion, rather than hopping. Lays strings of eggs in a single row.

Further reading:

Amphibians and Reptiles

A comprehensive guide to the native and non-native species of amphibian and reptile found in the British Isles. Professor Trevor Beebee covers the biology, ecology, conservation and identification of the British herpetofauna, and provides keys for the identification of adult and immature specimens as well as eggs, larvae and metamorphs.

Britain’s Reptiles and Amphibians

This detailed guide to the reptiles and amphibians of Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands has been produced with the aim of inspiring an increased level of interest in these exciting and fascinating animals. It is designed to help anyone who finds a lizard, snake, turtle, tortoise, terrapin, frog, toad or newt to identify it with confidence.

A Guide to the Reptiles and Amphibians of Britain and Ireland

This laminated pamphlet is produced by the Field Studies Council and covers the 13 species of non-marine reptile and amphibian which breed in Britain, as well as the five species which breed in Ireland. These include frogs, toads, newts, snakes and lizards.

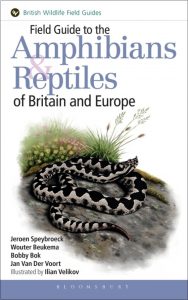

Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Britain and Europe

Field Guide to the Amphibians and Reptiles of Britain and Europe

This excellent field guide covers a total of 219 species, with a focus on identification and geographical variation. The species text also covers distribution, habitat and behaviour. Superb colour illustrations by talented artist Ilian Velikov depict every species.

The Amphibians and Reptiles of Scotland

The Amphibians and Reptiles of Scotland

This book is designed to be an interesting and informative guide to the amphibians and reptiles that are found in the wild in Scotland. The authors have focused on those species native to Scotland, plus those which are non-native but are breeding in the wild.

180ml Collecting Pot

180ml Collecting Pot