This is an updated version of a blog first published in 2020.

As static bat detectors continue to be more widely used and the technology improves, there are now many thousands of hours’ worth of nocturnal recordings captured each year from a vast spread of locations. This level of coverage has not only improved our ability to monitor bat populations, but also offers the potential to gather information on other animals that communicate at the same ultrasonic frequencies as bats. The calls of bush-crickets, for example, are commonly picked up as ‘by-catch’ during bat surveys, which has allowed the development of software that automatically recognises any cricket calls in a recording and assigns them to individual species.

Back in December 2020,?British Wildlife published an article by Stuart Newson, Neil Middleton and Huma Pearce exploring the potential – relatively untapped at that time – of acoustics for the survey of small terrestrial mammals (rats, mice, voles, dormice and shrews). Small mammals use their calls for a variety of purposes, including courtship, aggressive encounters with rivals and communication between parents and offspring. To the human ear, the high-pitched squeaks of different species sound much alike, but closer examination reveals them to be highly complex, extending beyond the range of our hearing into the ultrasonic and showing great variation in structure.

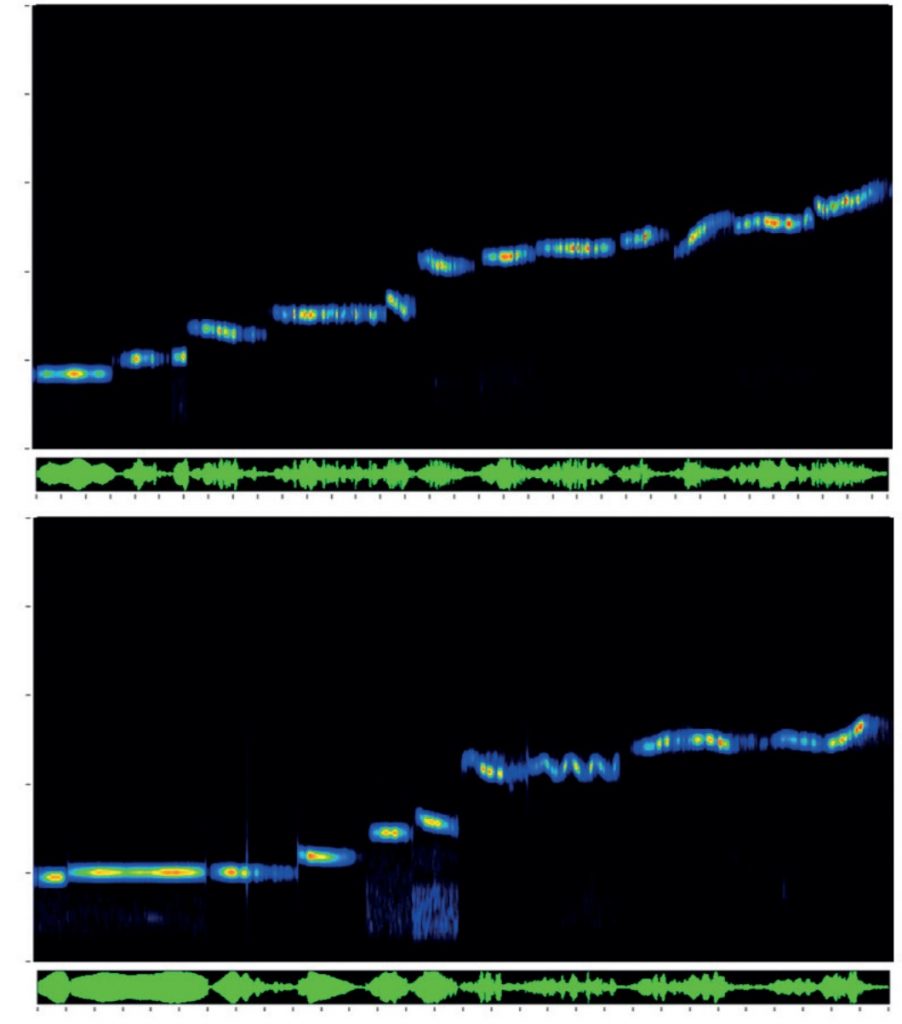

To answer the question of whether it’s possible to distinguish the calls of different species, the authors went through the time-consuming task of building a call library by taking recordings of all Britain’ native (and some non-native) small mammals. Call-analysis software was then used to examine the recordings and look for consistent differences between species, with some fascinating results – the calls of shrews, for example, can be readily separated from those of rodents by their warbling/twittering quality, while the house mouse typically calls at a higher frequency than any other species. Remarkably, it appears overall that the vocalisations of most species have their own diagnostic features, and that, with care, it should be possible to identify a high proportion of calls to species level. .

Small mammals are unobtrusive and hard to observe, which means that even the more familiar species, such as the Brown Rat, are severely under-recorded. Given how critically important small mammals are within the food chain, this lack of knowledge is a problem – one that is gaining increasing attention, including through the creation of a Small Mammal Research Working Group by the Mammal Society.

In the mission to improve understanding of small mammal populations, the ability to detect and identify species by their calls therefore offers great potential as a survey tool. Analysis of calls collected by static detectors – whether specifically set to target small mammals or deployed as part of a bat survey – is already providing a rich source of data and helping to complement traditional methods, such as the use of Longworth traps or footprint tunnels.

Furthermore, this method also shows promise for monitoring some of our most threatened small-mammal species. In Winter 2023, an article in Conservation Land Management described a novel trial in which static-acoustic detectors were used to monitor the protected Hazel Dormouse (you can read the article in full here), with positive results. Two years on, we spoke to Stuart Newson, coauthor of both articles and the pioneering Sound Identification of Terrestrial Mammals of Britain & Ireland, about more recent developments in this exciting field of ecological survey.

Stuart writes, “Since the publication of our article in Conservation Land Management, our understanding of Hazel Dormouse acoustic identification has continued to advance, alongside major improvements in the BTO Acoustic Pipeline’s ‘bat’ classifiers, for automatically detecting and identifying the calls of this species.

As with bats, potential identifications still require verification by visually inspecting spectrograms and listening to recordings. However, this process can now be carried out relatively routinely alongside bat sound identification.

As a proof of concept, Hazel Dormouse recordings from Great Britain (2021–2024) that were shared by users of the BTO Acoustic Pipeline were manually verified. This work has produced what we believe may be the first national-scale map of a small terrestrial mammal generated using acoustic data – and it just represents the beginning.

Over the next six months, and through a collaboration with APHA and funded by Defra, I, with the BTO will manually verify small terrestrial mammal detections (from .wav files) that have been identified as ‘by-catch’ within bat acoustic data submitted and shared by users of the BTO Acoustic Pipeline across the UK and Ireland.

The total number of verified identifications for Great Britain and Ireland is still to be determined. However, between 2021 and 2025, the wider (predominantly European) dataset already includes an incredible 1,177,597 small mammal identifications.

This planned project offers a unique opportunity to demonstrate the power of acoustic monitoring for identifying small terrestrial mammals at an unprecedented spatial scale. It will also create a large, novel dataset that has the potential to transform our understanding of these species – including insights into their seasonal and nightly vocal activity patterns across the UK and Ireland.”

To read about the key identification features of small-mammal calls, see the December 2020 issue of British Wildlife or, for all mammals, pick up a copy of Sound Identification of Terrestrial Mammals of Britain & Ireland. For more information and to contribute to the BTO Acoustic Pipeline visit the project’s webpage.

“She walked and travelled through the farms and uplands of Britain and Ireland. She talked to people on both sides of the divide – sheep-farmers, salmonfishers, raven-tamers, writers, scientists, conservationists, gamekeepers. She watched her chosen predators in the field and noted how they ‘fit into the landscape’.”

“She walked and travelled through the farms and uplands of Britain and Ireland. She talked to people on both sides of the divide – sheep-farmers, salmonfishers, raven-tamers, writers, scientists, conservationists, gamekeepers. She watched her chosen predators in the field and noted how they ‘fit into the landscape’.”

“In Woodland Flowers Keith Kirby invites us to look at the ‘wood beneath the trees’ and to consider what its flora can tell us. The focus of this, the eighth volume of Bloomsbury’s British Wildlife Collection (which I have contributed to myself), is on the vascular plants of the woodland floor; to this end Kirby embraces ferns as honorary flowers, but for the most part he steps aside from considering other elements of woodland ecosystems (including the ‘lower’ plants, fungi and fauna).”

“In Woodland Flowers Keith Kirby invites us to look at the ‘wood beneath the trees’ and to consider what its flora can tell us. The focus of this, the eighth volume of Bloomsbury’s British Wildlife Collection (which I have contributed to myself), is on the vascular plants of the woodland floor; to this end Kirby embraces ferns as honorary flowers, but for the most part he steps aside from considering other elements of woodland ecosystems (including the ‘lower’ plants, fungi and fauna).” “This is Sheldrake’s first book, and, while his expertise means that the readers should feel that they are in safe hands from the off, in truth the experience is more like being whisked down a burrow by a white rabbit, or on a tour of Willy Wonka’s research facility: a trippy, astonishing, and completely exhilarating ride.”

“This is Sheldrake’s first book, and, while his expertise means that the readers should feel that they are in safe hands from the off, in truth the experience is more like being whisked down a burrow by a white rabbit, or on a tour of Willy Wonka’s research facility: a trippy, astonishing, and completely exhilarating ride.” “Part autecology, part monograph and part impassioned love poem to a species that has captured the author’s heart, the pages offer an enjoyable blend of the Purple Emperor’s recorded history, biology, ecology and conservation.”

“Part autecology, part monograph and part impassioned love poem to a species that has captured the author’s heart, the pages offer an enjoyable blend of the Purple Emperor’s recorded history, biology, ecology and conservation.” “But do we really need a field guide to habitats? Possibly not. I certainly will not be taking my copy into the field. Yet this perhaps misses the point. What this book does is remind the users of other field guides that their organisms of interest do not live in isolation – they are nothing without their habitats. So, make this book an essential companion to your species guides.”

“But do we really need a field guide to habitats? Possibly not. I certainly will not be taking my copy into the field. Yet this perhaps misses the point. What this book does is remind the users of other field guides that their organisms of interest do not live in isolation – they are nothing without their habitats. So, make this book an essential companion to your species guides.” “Anyone interested in identifying and studying beetles simply cannot afford to be without [these books] and any quibbles can only be minor. Andrew cannot be too highly commended for his diligence and hard work to make so much information available to all.”

“Anyone interested in identifying and studying beetles simply cannot afford to be without [these books] and any quibbles can only be minor. Andrew cannot be too highly commended for his diligence and hard work to make so much information available to all.” “This is the latest book to enter the now relatively crowded marketplace of bumblebee guides, which may leave one wondering what it can offer to the more seasoned hymenopterist – read on! The author’s intention is to provide a book at the ‘entry level’ of bee study, Owens stating from the outset that he ‘aims to provide an easily accessible introduction for those with little or no previous knowledge of bumblebees’.”

“This is the latest book to enter the now relatively crowded marketplace of bumblebee guides, which may leave one wondering what it can offer to the more seasoned hymenopterist – read on! The author’s intention is to provide a book at the ‘entry level’ of bee study, Owens stating from the outset that he ‘aims to provide an easily accessible introduction for those with little or no previous knowledge of bumblebees’.” “There is no better place from which to view the tragi-comic events which unfold, and no better person to describe it than Derek Gow, a man of action as well as a powerful Beaver advocate. This account is unexpected, oddball, and, despite its serious side, enormously entertaining.”

“There is no better place from which to view the tragi-comic events which unfold, and no better person to describe it than Derek Gow, a man of action as well as a powerful Beaver advocate. This account is unexpected, oddball, and, despite its serious side, enormously entertaining.” “He has written an ecological masterpiece, generous in its sympathies, awe-inspiring in its breadth of knowledge, and genuinely enticing in its journey around heathland Britain. This is a book that ought to influence policy.”

“He has written an ecological masterpiece, generous in its sympathies, awe-inspiring in its breadth of knowledge, and genuinely enticing in its journey around heathland Britain. This is a book that ought to influence policy.”