Trees are a vital part of our ecosystems and essential to all life. As well as providing homes and food for a wide range of wildlife, they also provide us with oxygen and clean air, and they help to conserve water and stabilise the surrounding soil. As such, trees are invaluable both to our environment and for human well-being.

In the UK there are more than 60 native tree species, each with its own distinctive features that can help with identification. In this blog we will focus on ten of our most common native trees and provide you with the key characteristics you need to look out for – soon you’ll be confident in recognising oak from elder and silver birch from ash.

How to identify a tree:

The best time to identify a tree is when it is in leaf. By looking at the size and shape of the leaves/needles, the structure of the bark, and any other features present such as seeds, berries or flowers, you have a great chance of working out what the species is. It can be a bit more tricky if you’re looking in winter when the tree is bare, but there are several good books that will help you out (take a look at our recommended reading list at the bottom of this post for our top suggestions).

Ten common British trees and how to identify them:

1. Pedunculate oak (Quercus robur)

Where to find: Also known as common or English oak, this ancient tree is one of Britain’s most iconic species, standing tall for hundreds of years. It can be found across the country in both urban and rural areas. (Not to be confused with the sessile oak which is our other native species of oak – see below for tips on distinguishing between the two).

How to identify: The pedunculate oak is a large deciduous tree growing up to 40m tall. It has grey bark when young which becomes darker brown and develops long vertical fissures as it ages. Leaves have familiar deep-lobed margins with smooth edges. Acorns hang from the tree on long stalks.

Look out for: If you aren’t sure whether you’re looking at a pedunculate oak or a sessile oak, there are a couple of things you can check for. Pedunculate oak leaves have quite a short stem and more pronounced lobes at the bottom of the leaf. Acorns grow singly at the end of a long stem. Sessile oak leaves have a shorter stem and do not have lobes near the stem. Their acorns grow in clusters that are attached directly to the outer twigs.

2. Ash (Fraxinus excelsior)

Where to find: Ash is a common, widespread tree often found among British hedgerows and in many mixed deciduous woods in the UK.

How to identify: Ash grows up to a height of 30–40m. The bark is pale brown and fissures as the tree ages. Leaves are pinnately compound, usually comprising three to six opposite pairs of light green, oval leaflets. The buds are a sooty black with upturned grey shoots.

Look out for: Sadly, ash is also identified by a serious disease called ash dieback (or chalara) that is a substantial threat to the species. The fungus appears as black blotches on the leaves and affected trees usually die within a couple of years.

3. Common Lime (Tilia x europaea)

Where to find: The sweet smelling lime is native to much of Europe. Although rare in the wild, it is commonly found in parks and along residential streets.

How to identify: Common lime is a tall, broadleaf tree with dark green heart-shaped leaves which are are mostly hairless, except for cream or white hairs on the underside of the leaf between the joints of the veins. It is known for its sweet smelling white-yellow flowers, that hang in clusters of two to five and that develop into round, oval fruits with pointed tips.

Look out for: The common lime can be distinguished from other lime varieties by the tufts of white hair at the end of its twigs (in small-leaved lime hairs are red, and large-leaved lime has them all over the underside).

4. Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna)

Where to find: An ancient tree steeped in mythology and folklore, hawthorn is most commonly found growing in hedgerows, woodland and scrub.

How to identify: Hawthorn has dense, thorny foliage and, if left to fully mature, can grow to a height of 15m. The shiny lobed leaves are among the first to appear in spring. It’s five-petalled flowers are white or pink and grow in flat topped clusters. In autumn and winter, trees are covered in deep red fruits known as haws.

Look out for: This species often hybridises with the UK’s other native hawthorn, Midland hawthorn (Crataegus laevigata). They look very similar and can be hard to tell apart.

5. Hazel (Corylus avellana)

Where to find: Used regularly for coppicing, hazel can be found in a range of habitats, including woodlands, gardens and grasslands.

How to identify: A small shrubby tree with smooth, grey-brown bark, hazel can reach up to 12m in height if left uncoppiced. Its leaves are oval, toothed, and have soft hairs on their underside. In late winter, before the leaves have grown, it produces long yellow catkins that hang in clusters. These later develop into hazelnuts.

Look out for: Easily confused with English elm, they can be distinguished by the shape and feel of the leaves. Elm leaves have an asymmetric base and have rough feeling hairs. Hazel leaves are symmetrical at the base and feel soft and downy.

6. Common Alder (Alnus glutinosa)

Where to find: Common alder enjoys moist ground and so can be found along riversides, fens and wet woodlands, often providing shelter to fish. Interestingly, alder wood does not rot when it becomes wet, but instead becomes stronger and harder.

How to identify: Alder is a deciduous tree that grows to 25m. It is broadly conical in shape, and the bark is dark and fissured. Leaves are racquet-shaped and tough. Female catkins are present on the tree all year round and look like small green or brown cones. Male catkins also appear on the same tree and are longer and thinner. Alder can also be recognised by its purple buds and purple twigs with orange markings in winter.

Look out for: Can be confused with hazel – they can be told apart by the appearance of the leaves which are shiny and leathery in comparison to the soft downy leaves of the hazel.

7. Holly (Ilex aquifolium)

Where to find: A favourite in Christmas decorations, holly is widespread and found commonly in woodland, scrub and hedgerows.

How to identify: This easy-to-recognise evergreen tree has smooth bark with small warts and dark brown stems. Its shiny, leathery leaves usually have prickles along the edges, but can also be smooth in older trees. It can grow up to 15m in height and produces scarlet berries that remain on the plant throughout the winter.

Look out for: Although holly leaves usually have prickles, those on older trees or that are on the upper parts of the plant often have smoother edges.

8. White Willow (Salix alba)

Where to find: The weeping, romantic willow can be spotted growing in wet ground, often along riverbanks and around lakes where it trails its branches into the water.

How to identify: White willow is a the largest species of willow in the UK, growing up to 25m with an irregular, leaning crown. Its foliage appears silvery due to its pale, oval leaves that carry silky, white hairs on the underside. In early spring look out for its long yellow catkins and in winter try to spot the green-yellow narrow buds that grow close to the twig.

Look out for: There are several species of willow in the UK, including white willow, grey willow, weeping willow, goat willow and crack willow. These often hybridise in the wild.

9. Silver Birch (Betula pendula)

Where to find: A pioneer species, silver birch is a popular garden tree, and thrives in moorlands, heathland and dry and sandy soils.

How to identify: Silver birch can be easily recognised by its silver, papery bark which sheds like tissue paper. It has drooping branches and can reach 30m in height. Leaves are triangular-shaped with toothed edges and grow from hairless leaf stalks. In spring, flowers appear as yellow-brown catkins that hang in groups. Once pollinated, female catkins thicken and darken to a crimson colour.

Look out for: Silver birch is monoecious, meaning that both male and female catkins are found on the same tree. In April and May, try to distinguish the long yellow-brown male catkins from the short, erect green females ones.

10. Elder (Sambucus nigra)

Where to find: Historically known for its magical properties and hugely favoured by foragers, elder appears in hedges, scrub, woodland, waste and cultivated ground.

How to identify: Elder can grow to around 15m and has a short, greyish-brown trunk that develops deep creases as it ages. It has compound leaves; each leaf divided into five to seven leaflets. In summer, elder is recognised by its creamy, sweet-smelling white flowers that hang in sprays. In the autumn these develop into bunches of deep, purple berries.

Look out for: In winter, elder twigs are green and have an unpleasant smell. They have a white soft pith inside.

Recommended reading and guides:

Collins Tree Guide: The Most Complete Field Guide to the Trees of Britain and Europe

An essential, definitive guide to the trees of Britain and non-Mediterranean Europe. Containing some of the finest original tree illustrations ever produced, this is one of the most important tree guides to have appeared in the last 20 years.

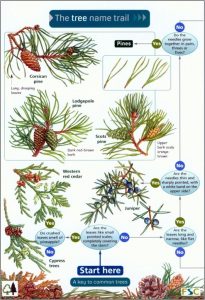

The Tree Name Trail: A Key to Common Trees

The Tree Name Trail: A Key to Common Trees

This 12-page laminated fold-out chart contains a full-colour illustrated key to the leaves, twigs, fruits and seeds of the commonest broadleaved and coniferous trees of Britain and Ireland.

Tree-Spotting: A Simple Guide to Britain’s Trees

A beautiful and captivating insight into the wonderful world of trees, Tree-Spotting burrows down into the history and hidden secrets of each species. It explores how our relationship with trees can be very personal, and hopes to bring you closer to the natural world around you.

Through beautiful full-page illustrations accompanied by key information about each tree, the First Book of Trees is designed to encourage young children’s interest in the outside world and the trees they encounter during their adventures.

Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Trees

Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Trees

A dendrochronological delight, the beautifully written and illustrated Tree Story reveals the utterly fascinating world of tree-ring research and how it matters to archaeology, palaeoclimatology and environmental history.

Winter Trees: A Photographic Guide to Common Trees and Shrubs

Winter Trees: A Photographic Guide to Common Trees and Shrubs

This AIDGAP guide covers 36 of the common broad-leaved deciduous species, or groups of species, that are most likely to be found in the UK, as well as a few rarer trees. It provides all the information you need to begin identifying trees in winter from their buds, bark, size and habitat.

Identification of Trees and Shrubs in Winter using Buds and Twigs

A practical guide to identifying trees and shrubs in winter. Comprehensive and easy to use, it contains over 700 species identifiable via their winter buds and twigs. The illustrated identification keys are easy to use, and a summary set of keys are provided as an appendix.

Why did you consider producing a second edition of The Vegetative Key to the British Flora and how long has it been in preparation?

Why did you consider producing a second edition of The Vegetative Key to the British Flora and how long has it been in preparation? Is there one easy mistake that can be made when identifying plants in their vegetative state?

Is there one easy mistake that can be made when identifying plants in their vegetative state?

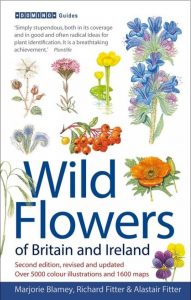

Marjorie Blamey 1918 – 2019

Marjorie Blamey 1918 – 2019 Marjorie Blamey, who died in September, aged 101, will be well-known to many as the artist of distinguished botanical field guides. Her paintings of wild flowers, trees and ferns are not only scientifically accurate but a joy to see in their fresh colours and lifelike arrangements. Her main aim, she once said, was to make plants look alive, and she achieved it by painting freshly gathered specimens, not, as many botanical artists did, by trying to breathe life into pressed ones.

Marjorie Blamey, who died in September, aged 101, will be well-known to many as the artist of distinguished botanical field guides. Her paintings of wild flowers, trees and ferns are not only scientifically accurate but a joy to see in their fresh colours and lifelike arrangements. Her main aim, she once said, was to make plants look alive, and she achieved it by painting freshly gathered specimens, not, as many botanical artists did, by trying to breathe life into pressed ones. Locating and painting around 2,000 different species for each field guide was quite a task. Marjorie and her husband Philip used to tour Europe in a motorised caravan, getting up at dawn to begin painting specimens gathered the previous afternoon, kept fresh in boxes lined with damp paper (at home she used the fridge or even the bath). In her prime she could get through a dozen watercolour paintings by lunch. Few botanical artists have worked so fast, and yet maintained such consistent quality.

Locating and painting around 2,000 different species for each field guide was quite a task. Marjorie and her husband Philip used to tour Europe in a motorised caravan, getting up at dawn to begin painting specimens gathered the previous afternoon, kept fresh in boxes lined with damp paper (at home she used the fridge or even the bath). In her prime she could get through a dozen watercolour paintings by lunch. Few botanical artists have worked so fast, and yet maintained such consistent quality. Her big break was the Collins Guide to Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe (1974) – known as ‘Fitter and Blamey’ – which was translated into many European languages and sold a million copies. It was followed by field guides to alpine flowers and Mediterranean flowers, vital identification guides to green tours ever since, and the large-format Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe (1989) which she wrote with her friend and mentor Christopher Grey-Wilson, and considered her best work. Her last field guide was the ambitious Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland (2003) – or ‘Fitter, Fitter and Blamey’ – whose 4,000-odd colour illustrations she completed at the age of 85 (adding yet more paintings to the revised edition ten years later).

Her big break was the Collins Guide to Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe (1974) – known as ‘Fitter and Blamey’ – which was translated into many European languages and sold a million copies. It was followed by field guides to alpine flowers and Mediterranean flowers, vital identification guides to green tours ever since, and the large-format Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe (1989) which she wrote with her friend and mentor Christopher Grey-Wilson, and considered her best work. Her last field guide was the ambitious Wild Flowers of Britain and Ireland (2003) – or ‘Fitter, Fitter and Blamey’ – whose 4,000-odd colour illustrations she completed at the age of 85 (adding yet more paintings to the revised edition ten years later). Despite her extraordinary output, Marjorie came to botanical painting surprisingly late. Although she had shown obvious talent in her youth – where she also became an accomplished actress, photographer and, after the outbreak of the Second World War, nurse and ambulance driver – she had largely given up painting to run a dairy farm in Cornwall with her husband, by whom she had four children. She was in her 40s when she began to paint local wild flowers. A friend persuaded her to exhibit, and one thing led to another: a book of magnolias, followed by the first of her field guides.

Despite her extraordinary output, Marjorie came to botanical painting surprisingly late. Although she had shown obvious talent in her youth – where she also became an accomplished actress, photographer and, after the outbreak of the Second World War, nurse and ambulance driver – she had largely given up painting to run a dairy farm in Cornwall with her husband, by whom she had four children. She was in her 40s when she began to paint local wild flowers. A friend persuaded her to exhibit, and one thing led to another: a book of magnolias, followed by the first of her field guides. Marjorie Blamey was modest about her talent. She seems to have loved the life of botanical travel, working all hours to complete her assignments. When you consider that the latest Collins Flower Guide took four artists a number of years to complete, and it took Keble Martin a whole lifetime to finish The Concise British Flora, her total of around 12,000 flower paintings for five major field guides, plus other work, begun in her 50s and ending in her 90s, is a record that will, I suspect, never be exceeded.

Marjorie Blamey was modest about her talent. She seems to have loved the life of botanical travel, working all hours to complete her assignments. When you consider that the latest Collins Flower Guide took four artists a number of years to complete, and it took Keble Martin a whole lifetime to finish The Concise British Flora, her total of around 12,000 flower paintings for five major field guides, plus other work, begun in her 50s and ending in her 90s, is a record that will, I suspect, never be exceeded.

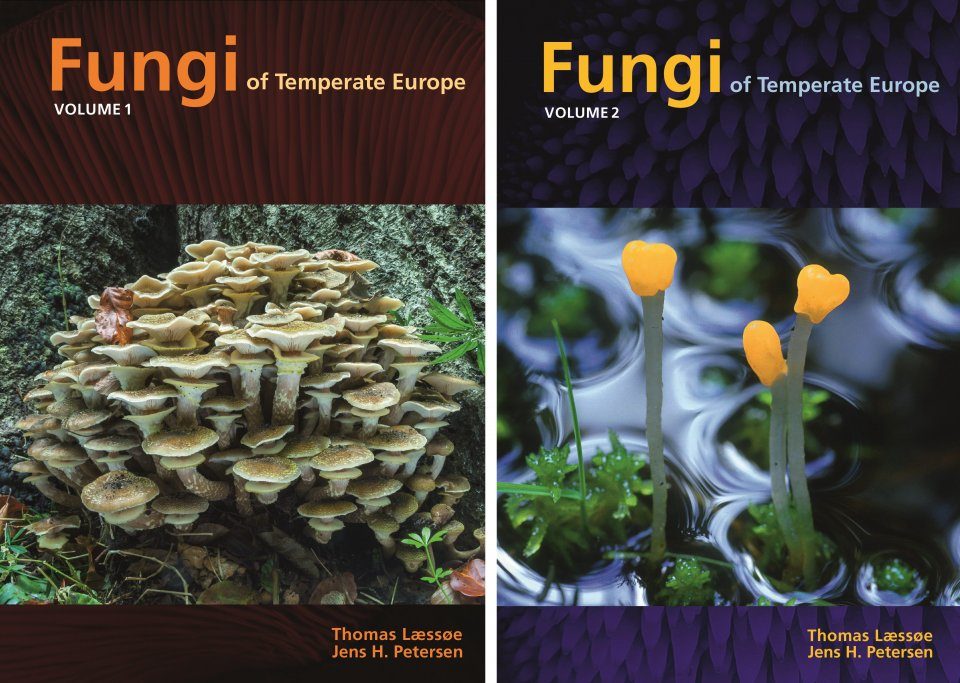

Could you tell us a little about your backgrounds and how you got interested in mycology?

Could you tell us a little about your backgrounds and how you got interested in mycology?  Two volumes, totalling over 1,700 pages must have a been a considerable undertaking; can you let us know a little of the process and how long it has taken for this book to come to fruition?

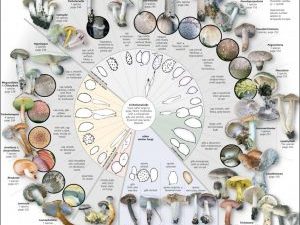

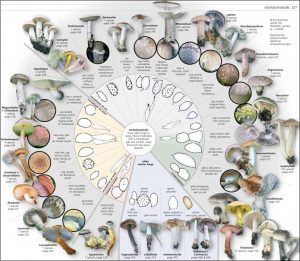

Two volumes, totalling over 1,700 pages must have a been a considerable undertaking; can you let us know a little of the process and how long it has taken for this book to come to fruition?  The book uses ‘form group’ to identify and present the fungi rather than exclusively strict taxonomic groups; what influenced you to use form groups and fungi wheels?

The book uses ‘form group’ to identify and present the fungi rather than exclusively strict taxonomic groups; what influenced you to use form groups and fungi wheels?  What is the biggest challenge when studying fungi?

What is the biggest challenge when studying fungi?  After such an endeavour you surely deserve a rest, but have either of you got any future projects planned that you can tell us about?

After such an endeavour you surely deserve a rest, but have either of you got any future projects planned that you can tell us about?

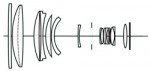

The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

despite the brand name this popular

despite the brand name this popular

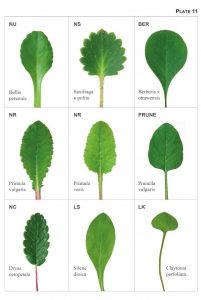

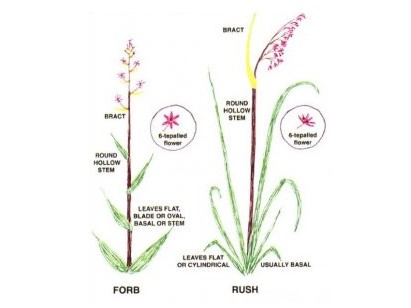

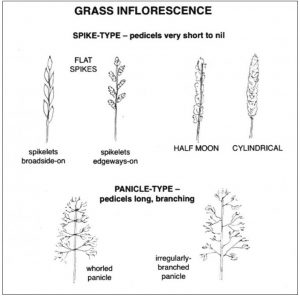

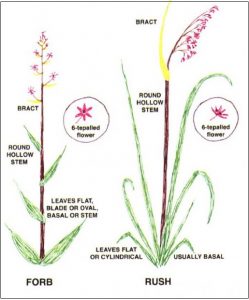

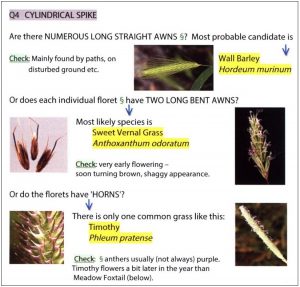

My books are not field guides at all. A field guide gives you a list of plant names, with pictures and descriptions, sometimes with a brief introduction. My books are all introduction: to field botany in general, to plant families and to grasses (maybe sedges and rushes next year . . .). A beginner armed only with a field guide has either to work their way from scratch through complicated keys, or to play snap: plant in one hand, book in the other; turn the pages until you find a picture that matches – ‘snap!’ By contrast, my books lead you into plant identification by logical routes, showing you where to look and what to look for. Their aim is to show you how to do ID for yourself.

My books are not field guides at all. A field guide gives you a list of plant names, with pictures and descriptions, sometimes with a brief introduction. My books are all introduction: to field botany in general, to plant families and to grasses (maybe sedges and rushes next year . . .). A beginner armed only with a field guide has either to work their way from scratch through complicated keys, or to play snap: plant in one hand, book in the other; turn the pages until you find a picture that matches – ‘snap!’ By contrast, my books lead you into plant identification by logical routes, showing you where to look and what to look for. Their aim is to show you how to do ID for yourself.

If you possibly can, go on a workshop for a day, a weekend or even a whole week. Having a real live person giving enthusiastic teaching, someone to answer all your questions and fresh plants to study is the best thing you can do. Look for a local botany or natural history group you can join, and go on their field meetings. When you get even a little more serious about your study, join Plantlife and/or the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland. Identiplant is a very good online course but it is not really suitable for absolute beginners. Be a bit careful with apps and websites: some are incredibly complex, some seem to be aimed at five-year-olds, others are just inaccurate and misleading. The best ID websites I am aware of are run by the

If you possibly can, go on a workshop for a day, a weekend or even a whole week. Having a real live person giving enthusiastic teaching, someone to answer all your questions and fresh plants to study is the best thing you can do. Look for a local botany or natural history group you can join, and go on their field meetings. When you get even a little more serious about your study, join Plantlife and/or the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland. Identiplant is a very good online course but it is not really suitable for absolute beginners. Be a bit careful with apps and websites: some are incredibly complex, some seem to be aimed at five-year-olds, others are just inaccurate and misleading. The best ID websites I am aware of are run by the  The main threat is not people picking a few to study, or even simply to enjoy at home. Climate change is, of course, a threat in one sense, but I believe we shouldn’t necessarily dread the rise of ‘aliens’ from warmer climates which are now able to establish themselves here. Every plant in Britain was once an alien, after the last Ice Age ended, and I would rather learn to live with change than blindly try to turn the clock back. There may be a few exceptions like Japanese Knotweed, but their evils are often exaggerated and some natives like bracken can be equally invasive. The real problem we face is habitat loss: to house-building and industry, land drainage, vast monocultural fields without headlands, destruction of ancient forests and so on. And this is an area where watchfulness and action really can make a difference.

The main threat is not people picking a few to study, or even simply to enjoy at home. Climate change is, of course, a threat in one sense, but I believe we shouldn’t necessarily dread the rise of ‘aliens’ from warmer climates which are now able to establish themselves here. Every plant in Britain was once an alien, after the last Ice Age ended, and I would rather learn to live with change than blindly try to turn the clock back. There may be a few exceptions like Japanese Knotweed, but their evils are often exaggerated and some natives like bracken can be equally invasive. The real problem we face is habitat loss: to house-building and industry, land drainage, vast monocultural fields without headlands, destruction of ancient forests and so on. And this is an area where watchfulness and action really can make a difference.

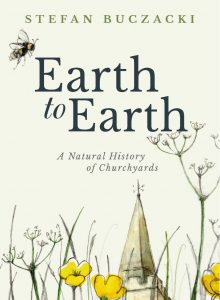

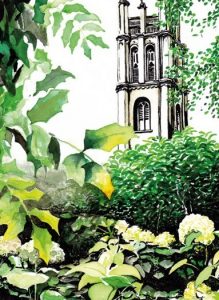

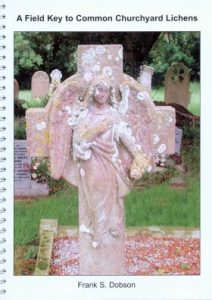

The unique features of churchyards mean that they offer a valuable niche for many species. Enclosed churchyard in particular provide a time-capsule and a window into the components of an ancient British landscape. Well known botanist, mycologist and broadcaster Stefan Buczacki has written

The unique features of churchyards mean that they offer a valuable niche for many species. Enclosed churchyard in particular provide a time-capsule and a window into the components of an ancient British landscape. Well known botanist, mycologist and broadcaster Stefan Buczacki has written

Managing a cemetery in a way that keeps everyone happy seems an impossible job. Last August I was photographing a meadow that had sprung up at a cemetery, when another photographer mentioned how disgusting it was. I was slightly bemused until the man explained he was a town councillor and was disgusted that the cemetery was unmaintained – “an insult to the dead” was how he described it – I thought it looked fantastic! whatever your opinion, how can we achieve common-ground between such diametrically opposed views?

Managing a cemetery in a way that keeps everyone happy seems an impossible job. Last August I was photographing a meadow that had sprung up at a cemetery, when another photographer mentioned how disgusting it was. I was slightly bemused until the man explained he was a town councillor and was disgusted that the cemetery was unmaintained – “an insult to the dead” was how he described it – I thought it looked fantastic! whatever your opinion, how can we achieve common-ground between such diametrically opposed views?

All the significant flora and fauna of churchyards their own chapters or sections; from fungi, lichen and plants, to birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals? Which class, order or even species do you think has the closest association with churchyards and therefore the most to gain or lose from churchyard’s future conservation status?

All the significant flora and fauna of churchyards their own chapters or sections; from fungi, lichen and plants, to birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals? Which class, order or even species do you think has the closest association with churchyards and therefore the most to gain or lose from churchyard’s future conservation status? With church attendance declining and the future of churchyard maintenance an increasingly secular concern; could you give a brief first-steps outline as to how an individual or a group might set about conserving and even improving the natural history of their local churchyard?

With church attendance declining and the future of churchyard maintenance an increasingly secular concern; could you give a brief first-steps outline as to how an individual or a group might set about conserving and even improving the natural history of their local churchyard? If someone, or a group become custodians of a churchyard what five key actions or augmentations would you most recommend and what two actions would you recommend against?

If someone, or a group become custodians of a churchyard what five key actions or augmentations would you most recommend and what two actions would you recommend against?

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book,

Carlos Magdalena is a botanical horticulturist at Kew Gardens, famous for his pioneering work with waterlilies and his never-tiring efforts to save some of the world’s rarest species from extinction. In his book,