Climate change is one of the most important issues of our time, with a wealth of publications released on this topic each year, exploring causes, impacts and potential solutions. In 2019, we put together this list of thought-provoking titles on climate change but, since then, many more key books have been published. In this post, we present an updated selection, including academic titles, handbooks, collaborations, introductory textbooks, children’s books and explorations of climate history.

General

The Climate Book

The Climate Book

Greta Thunberg | October 2022

This is an essential tool for everyone who wants to help save the world. Created in partnership with over one hundred experts, including geophysicists, oceanographers, economists, psychologists and philosophers, The Climate Book compiles their wisdom to equip us all with the knowledge we need to combat climate disaster.

Our Biggest Experiment: A History of the Climate Crisis

Our Biggest Experiment: A History of the Climate Crisis

Alice Bell | September 2022

Bell takes us back to climate change science’s earliest steps in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to the advancing realisation that global warming was a significant problem in the 1950s. It continues right up to today, where we have seen the growth of the environmental movement, climate scepticism and political responses like the UN climate talks.

Fire & Flood: A People’s History of Climate Change, from 1979 to the Present

Fire & Flood: A People’s History of Climate Change, from 1979 to the Present

Eugene Linden | April 2022

This is a definitive history of the modern climate-change era, from an award-winning writer who has been at the centre of the fight for more than thirty years. Fire & Flood is a comprehensive, compulsively readable history of climate change, drawing together the elements of the biggest story in the world.

Future on Fire: Capitalism and the Politics of Climate Change

Future on Fire: Capitalism and the Politics of Climate Change

David Carnfield | November 2022

This title argues that a just transition from fossil fuels and other drivers of climate change will not be delivered by business people or politicians that support the status quo. Nor will electing green left leaders be enough to overcome the opposition of capitalists and state bureaucrats. Only the power of disruptive mass social movements has the potential to force governments to make the changes we need.

Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction

Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction

Mark A Maslin | August 2021

This Very Short Introduction draws on science from the 2021 IPCC Report, examining the evidence that climate change is already happening, and discussing its potential catastrophic impacts in the future. Mark Maslin also explores the geopolitics of climate change and the win-win solutions we can employ to avoid the very worst effects of climate change.

Other key titles include Global Warming of 1.5°C: IPCC Special Report, Nomad Century, The Atlas of a Changing Climate and Food in a Changing Climate.

Physics / Climatology

The Physics of Climate Change

The Physics of Climate Change

Lawrence M Krauss | February 2021

This book provides a unique, clear, accurate and accessible perspective of climate science and the risks of global inaction. Krauss explores the history of how scientists progressed to our current understanding of the Earth’s climate and its future. This is required reading for anyone interested in understanding humanity’s role in the future of our planet.

Climate Change: What Science Tells Us

Climate Change: What Science Tells Us

Charles Fletcher | December 2021

This book introduces climate change fundamentals and essential concepts that reveal the extent of the damage, the impacts felt around the globe, and the innovation and leadership it will take to bring an end to the status quo.

Greenhouse Planet: How Rising CO2 Changes Plants and Life as We Know It

Greenhouse Planet: How Rising CO2 Changes Plants and Life as We Know It

Lewis H Ziska | October 2022

Greenhouse Planet reveals the stakes of increased CO2 for plants, people and ecosystems – from crop yields to seasonal allergies and from wildfires to biodiversity. The veteran plant biologist Lewis H. Ziska describes the importance of plants for food, medicine, and culture and explores the complex ways higher CO2 concentrations alter the systems on which humanity relies.

Introduction to Modern Climate Change

Introduction to Modern Climate Change

Andrew E Dessler | August 2021

The third edition of this introductory textbook for both science students and non-science majors has been brought completely up-to-date. As in previous editions, it is tightly focused on anthropogenic climate change, concentrating on the science of modern climate change, the carbon cycle, and the economics and policy options to address climate change.

Other titles include The Climate Demon, Meltdown and Beyond Global Warming.

Advice / Handbook

Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change

Net Zero: How We Stop Causing Climate Change

Dieter Helm | September 2021

Economist Dieter Helm addresses the action we all need to take to tackle the climate emergency: personal, local, national and global. Helm argues that we, the ultimate polluters, should pay based on how much carbon the products we buy produce. The goal of net-zero carbon emissions needs a rethink and Net Zero sets out how to do it in a plan that could and would work.

The Future We Choose: The Stubborn Optimist’s Guide to the Climate Crisis

The Future We Choose: The Stubborn Optimist’s Guide to the Climate Crisis

Christiana Figueres and Tom Rivett-Carnac | April 2021

This is a passionate call to arms from former UN Executive Secretary for Climate Change Christina Figueres, and Tom Rivett-Carnac, senior political strategist for the Paris Agreement. We are still able to stave off the worst and manage the long-term effects of climate change, but we have to act now. This is a book for every generation, for all of us who feel powerless in the face of the climate crisis.

The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times

The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times

Dame Jane Goodall and Douglas Abrams | July 2022

The world-renowned naturalist and conservationist Jane Goodall has spent more than a half-century warning of our impact on our planet. In The Book of Hope, Jane draws on the wisdom of a lifetime dedicated to nature to teach us how to find strength in the face of the climate crisis and explains why she still has hope for the natural world and for humanity.

What We Need to Do Now: For a Zero Carbon Future

Chris Goodall | February 2021

What We Need to Do Now is an urgent, practical and inspiring book that signals a green new deal for Britain. Drawing on actions, policies and technologies already emerging around the world, Chris Goodall sets out the ways to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 in the UK.

Fixing the Climate: Strategies for an Uncertain World

Fixing the Climate: Strategies for an Uncertain World

David G Victor and Charles F Sabel | September 2022

A compelling argument for solving the global climate crisis through local partnerships and experimentation. This book explains why the profound transformations needed for deep cuts in emissions must arise locally before best solutions can be spread globally. This is a road map to institutional design that can finally lead to self-sustaining reductions in emissions that years of global diplomacy have failed to deliver.

The Carbon Almanac

The Carbon Almanac

The Carbon Almanac Network | August 2022

This is a collaboration between hundreds of writers, researchers, thinkers and leaders that focuses on what we know, what has come before and what might happen next. With thousands of data points, articles and charts explaining carbon’s impact on everything in our society, it is the definitive source for facts and the basis for a global movement to fight climate change.

More titles include Hot Mess, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, Food and Climate Change Without the Hot Air and Pandora’s Toolbox.

Psychology

Minding the Climate: How Neuroscience Can Help Solve Our Environmental Crisis

Minding the Climate: How Neuroscience Can Help Solve Our Environmental Crisis

Ann-Christine Duhaime | October 2022

A neurosurgeon explores how our tendency to prioritize short-term consumer pleasures spurs climate change, but also how the brain’s amazing capacity for flexibility can – and likely will – enable us to prioritize the long-term survival of humanity.

How to Talk About Climate Change in a Way That Makes a Difference

How to Talk About Climate Change in a Way That Makes a Difference

Rebecca Huntley | January 2021

Why is it so hard to talk about the future of our Earth? Rebecca Huntley’s book explores why the key to progress on climate change is in the psychology of human attitudes and our ability to change. This is about understanding why people who aren’t like you feel the way they do and learning to talk to them effectively.

We’re All Climate Hypocrites Now: How Embracing Our Limitations Can Unlock the Power of a Movement

We’re All Climate Hypocrites Now: How Embracing Our Limitations Can Unlock the Power of a Movement

Sami Grover | October 2021

Taking a tongue-in-cheek approach, self-confessed eco-hypocrite Sami Grover says we should do what we can in our own lives to minimise our climate impacts, but then we need to target those actions so they create systemic change. Along the way, he skewers those pointing fingers, celebrates those who are trying and offers practical pathways to start making a difference.

Warning

Our Final Warming: Six Degrees of Climate Emergency

Our Final Warming: Six Degrees of Climate Emergency

Mark Lynas | March 2021

Mark Lynas delivers a vital account of the future of our earth, and our civilisation, if current rates of global warming persist. And it’s only looking worse. These escalating consequences can still be avoided, but time is running out. This book must not be ignored, it really is our final warning.

Hope in Hell: A Decade to Confront the Climate Emergency

Jonathon Porritt | August 2021

Porritt believes we have time to do what needs to be done, but only if we move now – and move together. In this ultimately optimistic book, he explores all these reasons to be hopeful: new technology; the power of innovation; the mobilisation of young people – and a sense of intergenerational solidarity as older generations come to understand their own obligation to secure a safer world for their children and grandchildren.

Climate change denial

Hot Air: The Inside Story of the Battle Against Climate Change Denial

Hot Air: The Inside Story of the Battle Against Climate Change Denial

Peter Scott | August 2022

Climate scientist and MET Science Fellow Peter Stott reveals the bitter fight to get international recognition for what, among scientists, has been known for decades: human activity causes climate change. Hot Air is the urgent story of how the science was developed, how it has been repeatedly sabotaged and why humanity hasn’t a second to spare in the fight to halt climate change.

The Power of Narrative: Climate Skepticism and the Deconstruction of Science

The Power of Narrative: Climate Skepticism and the Deconstruction of Science

Raul P Lejano and Shondel J Nero | October 2021

This examines the strength of climate scepticism as a story, offering a thoughtful analysis and comparison of anti-climate science narratives over time and across geographic boundaries. This is a book about how our society understands and interacts with science, how a social narrative becomes ideology, and how we can move beyond personal and political dogma to arrive at a sense of collective rapprochement.

Habitat / Species

Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis

Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis

Annie Proulx | September 2022

From Pulitzer Prize-winner Annie Proulx comes a riveting, revolutionary history of our wetlands, their ecological role and what their systematic destruction means for the planet. A sobering look at the degradation of wetlands over centuries and the serious ecological consequences, this is a stunningly important work and a rousing call to action by a writer whose passionate devotion to understanding and preserving the environment is on full and glorious display.

Nowhere Left to Go: How Climate Change Is Driving Species to the Ends of the Earth

Nowhere Left to Go: How Climate Change Is Driving Species to the Ends of the Earth

Benjamin von Brackel | July 2022

The lengths plants and animals must go to avoid extinction are as alarming as they are inspirational: sea animals – like fish – move on average 45 miles a decade to cooler regions, while land animals – like beavers and butterflies – move 11 miles. As even the poles of the Earth heat up, we’re left with a stark and irreversible choice: halt the climate emergency now, or face a massive die-off of species, who are increasingly left with nowhere else to go.

Hurricane Lizards and Plastic Squid: How the Natural World is Adapting to Climate Change

Hurricane Lizards and Plastic Squid: How the Natural World is Adapting to Climate Change

Thor Hanson | February 2022

This is the first major book by a biologist to focus on the fascinating story of how the natural world is adjusting, adapting and sometimes measurably evolving in response to climate change. Lyrical and thought-provoking, this book broadens the climate focus from humans to the wider lattice of life.

Children’s books

Climate Emergency Atlas: What’s Happening – What We Can Do

Climate Emergency Atlas: What’s Happening – What We Can Do

Dan Hooke | October 2020

Packed with facts and figures and more than 30 dynamic maps, Climate Emergency Atlas is clear and easy to understand, making it the perfect reference guide for all young climate activists. This unique graphic atlas tells you everything you need to know about the current climate emergency, and what we can do to turn things around.

A Short, Hopeful Guide to Climate Change

A Short, Hopeful Guide to Climate Change

Oisín McGann | May 2021

What is climate change? How can it be stopped? And what can young people do to help the fight? Author Oisín McGann explains climate change science and encourages young people to be part of positive change by getting involved in the global movement to fight humanity’s biggest challenge. This book is also eco-friendly, with vegan inks, all recycled materials and fully recyclable – this book is part of the solution.

How to Change Everything: The Young Human’s Guide to Protecting the Planet and Each Other

How to Change Everything: The Young Human’s Guide to Protecting the Planet and Each Other

Naomi Klein and Rebecca Stefoff | March 2022

This is the most authoritative and inspiring book on climate change for young people yet, discussing the effects of climate change, how young people are fighting back and how you can get involved to make the world a safer and better place. This gives a powerful picture of why and how the planet is changing, providing effective tools for action so that YOU really can make a difference.

Upcoming titles

Ecology of a Changing World

Ecology of a Changing World

Trevor Price | December 2022

This book outlines the importance of species conservation relative to human existence. It breaks down ecological principles and explains six threats to biodiversity in terms anyone studying ecology, evolutionary biology, environmental science or environmental justice will understand. These threats are climate change, overharvesting, pollution, habitat loss, invasive species and disease, with Price offering the history, current status and economic and environmental impacts of each of these.

Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know

Climate Change: What Everyone Needs to Know

Joseph Romm | December 2022

This is the essential primer on what will be the defining issue of our time. Newly updated with the latest in climate science from COP26 and beyond, this third edition offers user-friendly, scientifically rigorous answers to the most difficult (and commonly politicised) questions surrounding climate change.

Outsourcing Climate Breakdown: How Rich Nations Get Away With It

Outsourcing Climate Breakdown: How Rich Nations Get Away With It

Laurie Parsons | May 2023

Around the world, leading economies are announcing significant progress on climate change. World leaders are queuing up to proclaim their commitment to tackling the climate crisis. Yet the atmosphere is still warming at a record rate. Outsourcing Climate Breakdown explores the murky practices of exporting a country’s environmental impact., taking a wide-ranging, culturally engaged approach to the topic and showing that this is not only a technical problem, but a problem of cultural and political systems and structures.

You can browse our full collection of climate change titles here. We also have a number of blogs on the current challenges we face with climate change here.

Image credit: Mike Lewelling, National Park Service via Flickr

As a zoological professional you have studied and worked in several esteemed organisations including the University of Bristol, London Zoo and Oxford-Brookes University. What do you consider to be the most significant highlights of your career so far?

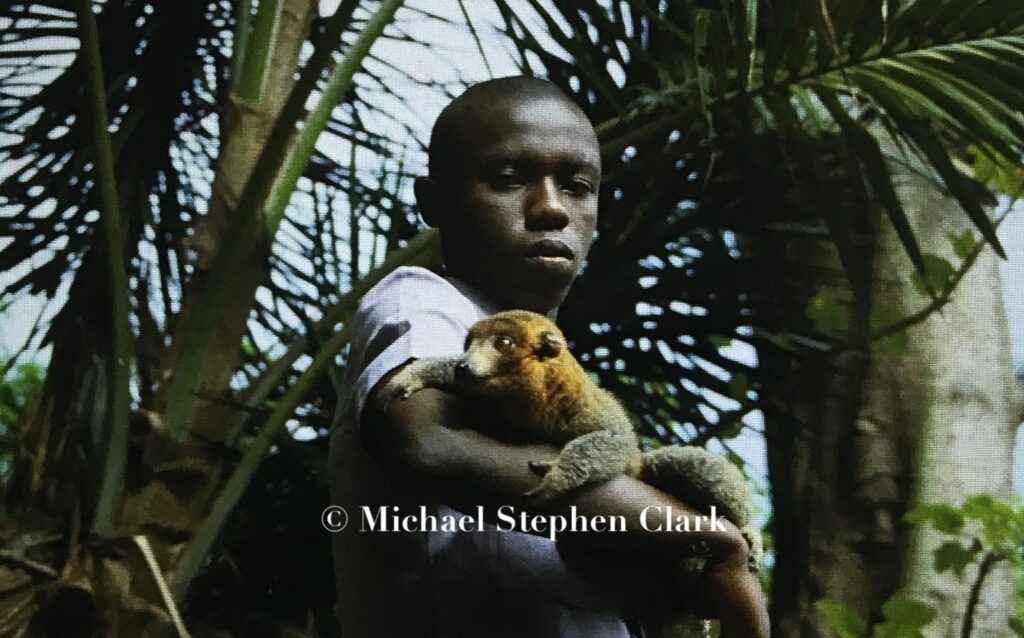

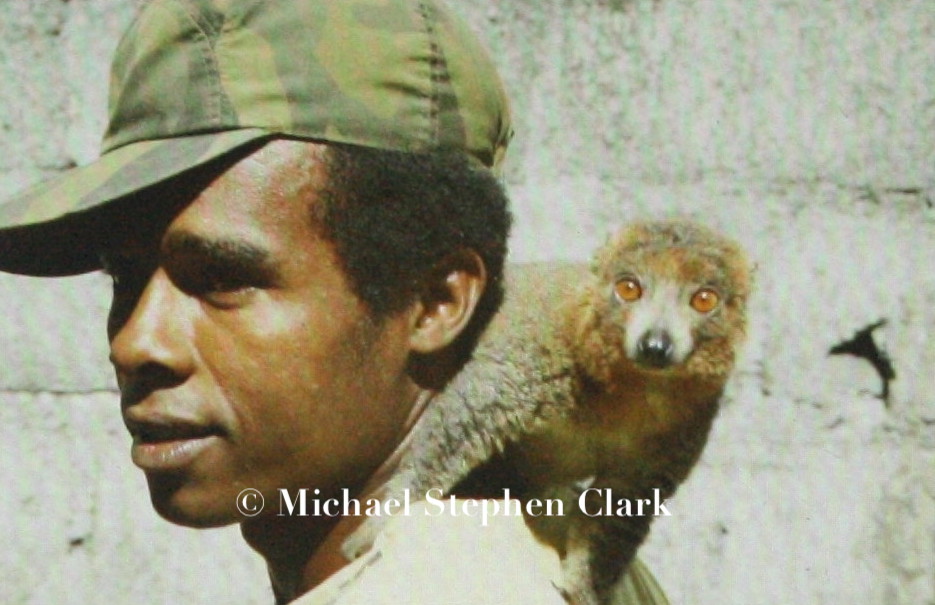

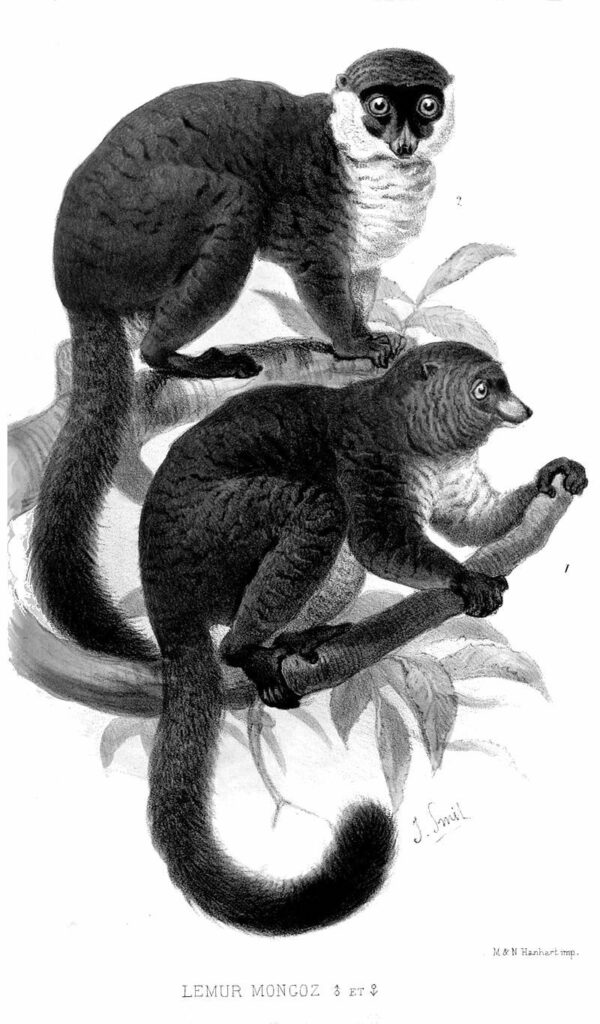

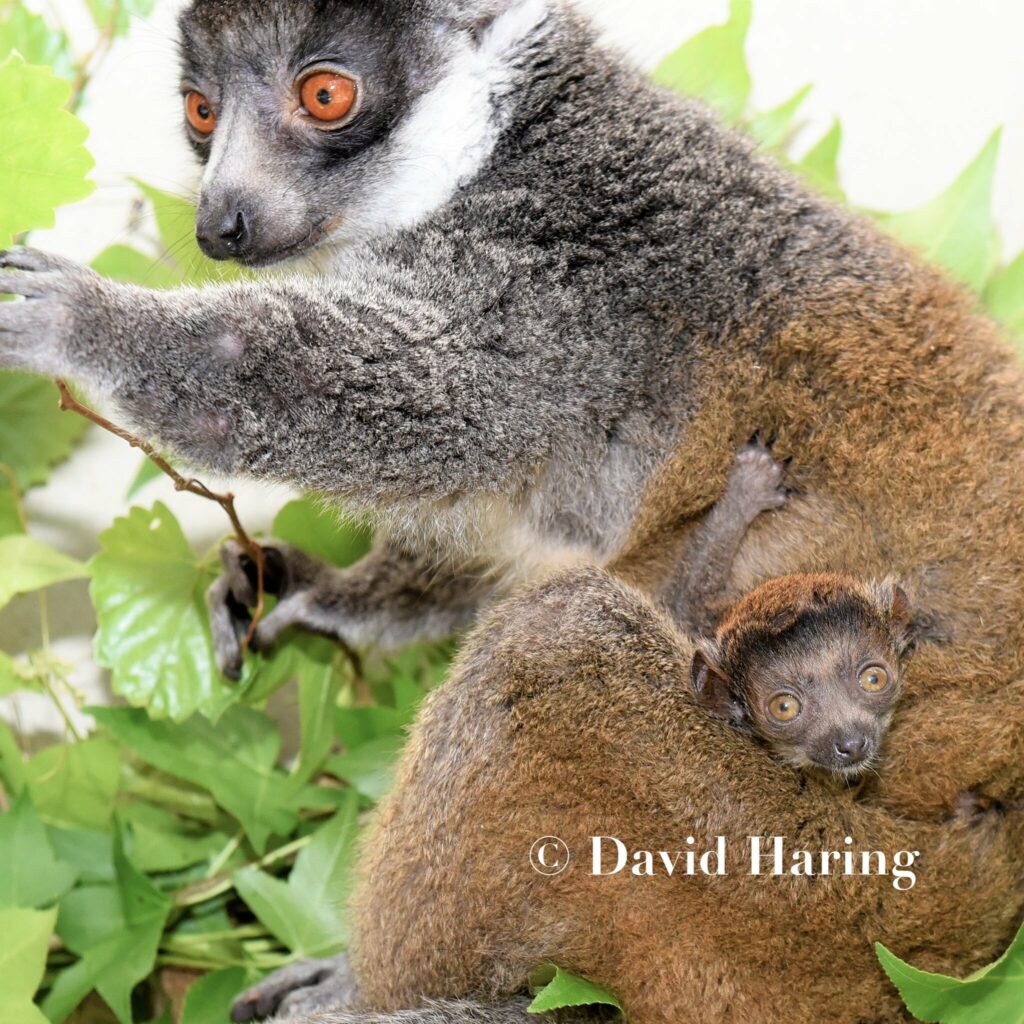

As a zoological professional you have studied and worked in several esteemed organisations including the University of Bristol, London Zoo and Oxford-Brookes University. What do you consider to be the most significant highlights of your career so far? The Fragmented World of the Mongoose Lemur is, in large part, a species-specific natural history – a format that is perhaps less popular than it has been in previous years and decades. The book was also published independently. How did you find the process of planning, writing and publishing the book and what were the main challenges you faced?

The Fragmented World of the Mongoose Lemur is, in large part, a species-specific natural history – a format that is perhaps less popular than it has been in previous years and decades. The book was also published independently. How did you find the process of planning, writing and publishing the book and what were the main challenges you faced?

• Peaking in late November and early December, Starling murmurations are one of the most spectacular events in the wildlife watcher’s year. These magnificent clouds of birds, swirling and turning in perfect unison, can be made up of more than 100,000 individuals. The best time to see murmurations is in the early evening – this is when the birds take to the skies to find their night-time roosting spots.

• Peaking in late November and early December, Starling murmurations are one of the most spectacular events in the wildlife watcher’s year. These magnificent clouds of birds, swirling and turning in perfect unison, can be made up of more than 100,000 individuals. The best time to see murmurations is in the early evening – this is when the birds take to the skies to find their night-time roosting spots. • October is the ideal time to observe the deer rut. Our three largest species of deer (red, fallow and sika) all perform this spectacular behaviour which involves rival stags roaring and locking antlers in battle in order to gain access to females, who are only fertile for around one day each year. Exmoor, Dartmoor and the New Forest are particularly good locations for observing these iconic displays.

• October is the ideal time to observe the deer rut. Our three largest species of deer (red, fallow and sika) all perform this spectacular behaviour which involves rival stags roaring and locking antlers in battle in order to gain access to females, who are only fertile for around one day each year. Exmoor, Dartmoor and the New Forest are particularly good locations for observing these iconic displays. • During the autumn, salmon will migrate from the open ocean back to their home rivers in an effort to reach the higher reaches of clean water where they will breed. As they travel upstream they can jump up to three metres upon encountering waterfalls or other obstacles. Although risky for the fish, as jumping out of the water makes them vulnerable to predation, these spots provide an excellent chance for us to observe the salmon run in action.

• During the autumn, salmon will migrate from the open ocean back to their home rivers in an effort to reach the higher reaches of clean water where they will breed. As they travel upstream they can jump up to three metres upon encountering waterfalls or other obstacles. Although risky for the fish, as jumping out of the water makes them vulnerable to predation, these spots provide an excellent chance for us to observe the salmon run in action.

• Bee orchids (Ophrys apifera) will flower briefly in June and July on dry, chalk and limestone grasslands, while sea cliffs will be adorned with the delicate blush of sea thrift (Armeria maritima) from April to October.

• Bee orchids (Ophrys apifera) will flower briefly in June and July on dry, chalk and limestone grasslands, while sea cliffs will be adorned with the delicate blush of sea thrift (Armeria maritima) from April to October. • June to August is an important time for ladybirds. During this period, mated females will lay their eggs which then hatch into larvae and form pupae through a series of four stages, or ‘instars’. Adult ladybirds emerge from the pupae in August.

• June to August is an important time for ladybirds. During this period, mated females will lay their eggs which then hatch into larvae and form pupae through a series of four stages, or ‘instars’. Adult ladybirds emerge from the pupae in August. • The summer months are a great time to spot bats hunting for insects during the dusk and dawn hours. Female bats give birth to their young in June and within three weeks these juveniles will be learning to fly themselves. By August the youngsters will no longer need their mother’s milk and will be hunting for their own food.

• The summer months are a great time to spot bats hunting for insects during the dusk and dawn hours. Female bats give birth to their young in June and within three weeks these juveniles will be learning to fly themselves. By August the youngsters will no longer need their mother’s milk and will be hunting for their own food.