An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe is a photographic guide to 75 species of bird most commonly found in or over the gardens of Britain and North-West Europe. The text combines scientific facts with affectionate descriptions of the birds’ identifying features, including sex and age differences, habits, nest types, eggs and calls. The introduction contains tips on how to identify birds, how to look after garden birds, which species can be seen throughout the year, a glossary and anatomy details. For each species, there are two or three photographs labelled with distinguishing features where appropriate, a calendar showing the time of year when the adult can be seen and star facts that give further proof of the birds’ fascinating features.

An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe is a photographic guide to 75 species of bird most commonly found in or over the gardens of Britain and North-West Europe. The text combines scientific facts with affectionate descriptions of the birds’ identifying features, including sex and age differences, habits, nest types, eggs and calls. The introduction contains tips on how to identify birds, how to look after garden birds, which species can be seen throughout the year, a glossary and anatomy details. For each species, there are two or three photographs labelled with distinguishing features where appropriate, a calendar showing the time of year when the adult can be seen and star facts that give further proof of the birds’ fascinating features.

Dominic Couzens is an award-winning nature writer with 40 books and hundreds of published articles to his name. His best-known books include An Identification Guide to Garden Insects of Britain and North-West Europe, The Secret Lives of Garden Birds, Britain’s Mammals (WildGuides) and Save Our Species. Carl Bovis is a nature photographer with a particular passion for birds. The advent of digital photography has given him the opportunity to capture the birds he sees and share them with the world.

We were lucky enough to ask both Dominic and Carl a few questions about what inspired them to produce this guide, what the process was like to assemble it and the importance of providing habitats for birds in our gardens.

What inspired you to produce this introductory guide to garden birds?

Dominic: As a regular Twitter follower I quickly became aware of Carl’s work. What stood out for me was his wonderfully giving attitude, really helping “ordinary” people connect with birds and birdwatching with the use of clever and funny bird photos, as well as wondrous ones. He encourages everyone to get involved and to enjoy nature, and he does it in a unique way.

So from my (Dominic’s) point of view, it was a no-brainer to cooperate with Carl on an entry-level guide to garden birds, with his own special take.

This book follows on from a book on garden insects published with another first-time author, Gail Ashton, last year. In both guides we have used light-hearted introductions and mentioned star facts about each species, to helve delve into the subject’s life.

How did you choose which species to include in this guide?

Our subject was garden birds, and since we wanted to cover northern Europe we had a good range to choose from. Most species pick themselves, but the guide will stand or fall on what we include.

This guide is full of many wonderful and illustrative photographs. What was the process like to assemble these? Where there any species that were particularly difficult to attain clear photos of?

Carl: I’m known for taking photos of the common birds, a lot of which many serious bird photographers turn their noses up at! So a book about garden birds was perfect for me, as I have taken many photos of them over the last few years and had many to choose from. I also have a passion for catching birds in flight, the shape and angles of their wings and tail fascinate me. Obviously this is an ID book, so perched birds are essential, but we’ve included lots of flight shots too.

It’s very rewarding for me to have my photos in this guide. A couple of years ago I was talking to a serious birder at Steart Marshes and he said to me; ‘your photos of birds are very engaging, but they’d never be in a mainstream bird book’. I didn’t take offence, I like that many of my photos are different to the norm, but at the same time, I’m happy now to have proved him wrong!

It’s also an honour to collaborate with Dominic on this, as before I even knew him personally, I had bought and enjoyed many of his previous books, and had attended one of his fascinating talks on bird behaviour. He is nature-writing ‘royalty’ as far as I’m concerned.

The shy and rarer garden birds were obviously toughest to get clear photos of, especially ones that don’t visit my own little Somerset garden where many of the photos were taken. So birds like Bullfinch, Treecreeper and Redstart were a challenge. If you get them in your garden, consider yourself lucky!

Included with this interview are a few of my favourite photos from the book.

Given the many pressures facing our garden birds, are there any species in this guide that you think won’t be so common in coming years?

Dominic: We have included a number that are declining, such as Marsh and Willow Tits, Chaffinches and Greenfinches. The Lesser Spotted Woodpecker is in serious trouble, and both House Martins and Swifts are on the wane. There are others, too.

But I do think it’s very important to let people just discover and enjoy birds. I hope the book inspires first and foremost.

This guide includes a section on looking after garden birds, giving tips as to how people with gardens can help. How important is it that people make their gardens into good habitats for birds?

Dominic: Gardens are incredibly important for two reasons. They are the best place for people and birds to meet, and for people to get excited about birds and love them.

Secondly, gardens are where everybody can be a conservationist. The overall fortunes of birds and other wildlife often feel as though they are outside our control, but in gardens we can make decisions that directly affect wildlife. If enough people realised how important their backyard decisions were to wildlife, they might be inspired to do more.

Are there any plans to continue this series and, if so, which other species groups that you would like to make an identification guide about?

Dominic: Yes, a book on Trees is already well in production. Any others in the series may require us to get John Beaufoy, our publisher, drunk so that we can persuade him to do some more.

An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe by Dominic Couzens and Carl Bovis is published by John Beaufoy Publishing in June 2023 and is available from nhbs.com.

An Identification Guide to Garden Birds of Britain and North-West Europe by Dominic Couzens and Carl Bovis is published by John Beaufoy Publishing in June 2023 and is available from nhbs.com.

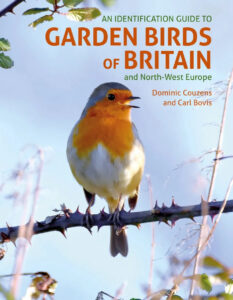

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

Helen Read is a Conservation Officer for the City of London Corporation based at Burnham Beeches, a post held for over 30 years. She has written numerous books and papers on a variety of subjects, the majority being on the management of veteran trees and topics relating to invertebrates. She has also been an active committee member in various invertebrate societies.

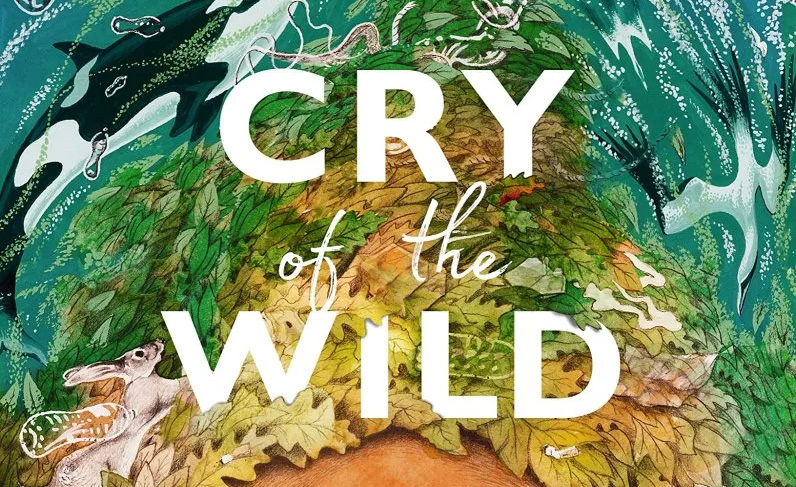

The Book of Wilding, while being a hugely practical guide to rewilding on all scales, is also a beacon of hope. In an age when eco-anxiety can lead even the most optimistic and determined of us to feel despondent, do you feel broadly hopeful that humans can do the necessary work to restore balance to our planet?

The Book of Wilding, while being a hugely practical guide to rewilding on all scales, is also a beacon of hope. In an age when eco-anxiety can lead even the most optimistic and determined of us to feel despondent, do you feel broadly hopeful that humans can do the necessary work to restore balance to our planet?  Do you think that there are some misconceptions as to what constitutes rewilding? Particularly on a smaller scale where a more hands-on approach might be required to mimic the natural processes of herbivores, for instance – to the untrained eye this might seem more like conventional conservation management than rewilding.

Do you think that there are some misconceptions as to what constitutes rewilding? Particularly on a smaller scale where a more hands-on approach might be required to mimic the natural processes of herbivores, for instance – to the untrained eye this might seem more like conventional conservation management than rewilding.  Finally – what steps would you recommend to the ‘average’ citizen who isn’t a large landowner or farmer and wants to go beyond simply rewilding their own small garden?

Finally – what steps would you recommend to the ‘average’ citizen who isn’t a large landowner or farmer and wants to go beyond simply rewilding their own small garden?