The High Seas Treaty is a new agreement signed by the UN which aims to put 30% of international waters into marine protected areas (MPAs) by 2030. International waters are two-thirds of the world’s ocean, established under the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, where all countries have a right to fish, ship and conduct research. Currently, only 1.2% of these areas are protected, leaving the rest open to exploitation from a wide variety of threats.

What are the current threats to the world’s oceans?

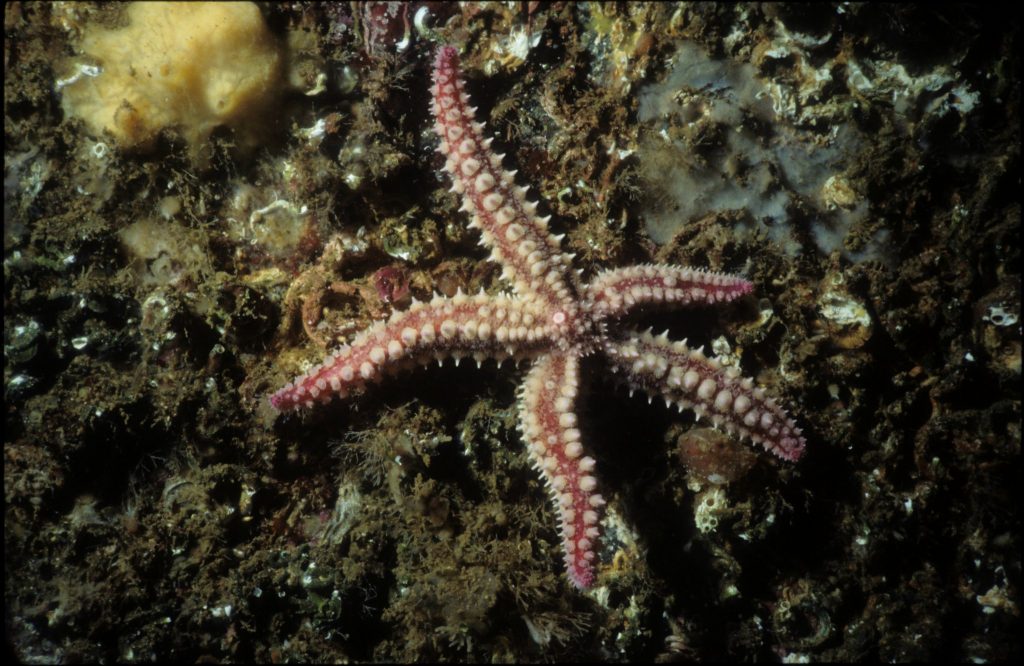

There are a number of key threats to the health of our oceans. A recent assessment by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) found that nearly 10% of marine species are at risk of extinction. Overfishing and pollution are the two biggest threats, according to the Nigerian Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research. The number of overfished stocks has tripled globally in the last 50 years and, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, one-third of the world’s assessed fisheries are being pushed beyond biological limits. Illegal fishing, under-researched, unbacked or unregulated fishing quotas, and bycatch all combine to create a major threat to global marine ecosystems.

Around 4 million fishing vessels are currently in operation around the globe. Poor government management and control of fisheries and trade, along with subsidies provided by many governments to offset business costs and a criminal fishing network worth around $36.4 billion annually, are all serving to drive overfishing. This leads to degraded ecosystems, changes in biotic factors such as abundance, average fish size, reproduction strategies and speed of maturation, leading to imbalances between predator and prey dynamics that can erode food webs.

While plastic pollution is often the most discussed type of marine pollution, there are actually a broad number of sources, including chemicals and excess nutrients from agricultural runoff, industrial wastewater and sewage, oil spills, ocean acidification and other non-biodegradable waste. They can be broadly grouped into two categories: chemicals and trash. Chemical pollution creates negative effects on the marine environment by changing the chemical state of the ocean, artificially increasing nutrient levels which can lead to toxic algal blooms and impacting the physiology of marine life by reducing their capacity to reproduce, reducing offspring fitness, impacting growth or increasing their vulnerability to parasites and diseases. Marine trash can cause entanglement or be consumed, which can impact the health of marine life and even become fatal.

Other threats include those from shipping traffic, such as noise and collisions, climate change, deep-sea drilling or mining, weapons testing and sonar. Climate change impacts the oceans in a variety of complex ways, from sea level rises changing the abiotic factors of many habitats, temperature rises causing marine heat waves, more frequent and intense storms, and changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide levels leading to anoxic water and ocean acidification. Shipping noise, mining, weapons testing and sonar produce high levels of sound waves in the ocean, disrupting marine communication and impacting the behaviour of species such as whales, causing them to travel miles away and even beaching themselves to avoid the disturbance. All these stressors impact marine life, leading to mass mortality events and threatening ecosystems.

What is the plan?

The talks, called the Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction, have now reached an agreement on the legal framework after almost 20 years. One of the main elements of this treaty is the aim to create international MPAs, restricting industrial fishing, deep-sea mining and other potentially destructive activities. Another part of the treaty looks to reassess environmental impact assessments, creating consistent ground rules that all nations will need to follow when calculating the potential damage of human activities in these areas. It would also open up the sharing of genetic resources from international waters, which has both scientific and commercial benefits.

Will this be effective?

More than 100 countries are part of this agreement. While the treaty has been agreed upon, it is not yet been ‘legally agreed’, meaning that the treaty must first be formally adopted and then be passed legally into all the countries that have signed up. Effective implementation is crucial, as if all countries do not abide by the new treaty, it will not have the full impacts that are desired. Talks have previously been held up due to a number of disagreements over fishing rights and funding.

For MPAs to be effective, they need to be properly regulated and enforced. This means that fishing quotas must be backed by thorough research, catch numbers need to be reported accurately and illegal fishing must be controlled. Many existing MPAs fail to protect marine biodiversity and keep fishing to sustainable levels, according to a report by the European court of auditors. A study even found that 59% of the MPAs in Europe were being trawled by commercial vessels more often than in areas without protection. Therefore, without proper and rigorous regulation, these areas will simply provide a false sense of security without any actual progress in conserving and restoring our marine biodiversity.

Additionally, while creating MPAs that would regulate fishing, shipping routes and research such as deep-sea mining, it does not protect from the other threats to marine health. Over 80% of marine pollution comes from land-based activities, therefore these new MPAs will continue to be threatened by pollution. They will also still be threatened by the impacts of climate change, although intact ecosystems are much more resilient to these stressors than degraded ones. Therefore, if these new MPAs can repair biodiversity in these areas, some of the effects of these threats could be at least partially mitigated.

To aid the approval of the treaty and its early implementation, the EU pledged €40m (£35m). The continued success of this, however, requires continued funding. This is why countries will still be allowed to profit from marine genetic resources, as a proportion of this will need to be placed into a global fund. High-income countries may be asked to contribute more, and the fund will need to be regulated to make sure the correct contributions are being made and that funds are being used effectively and fairly.

Summary

- This new UN treaty will place 30% of international waters into Marine Protected Areas by 2030, restricting fishing, mining and other destructive marine activities.

- The marine ecosystem is under threat from a variety of sources, including pollution, overfishing and climate change.

- The MPAs will need to be properly regulated. This treaty will not protect the areas from all threats but, if the ecosystems become more intact and stable, this will help to mitigate some of the impacts.

- Funding will need to be continuous and used fairly and effectively for this treaty to be successfully implemented.