The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

The possession of a hand lens is one of the defining characteristics of a naturalist.

We use them for everything from peering at beetle genitalia and examining floral characters, to examining the arrangement of teeth in small mammal jaw bones. There are a wide variety of hand lenses on the market so how do you decide which lens is best for you? This article contains all the information you need to make an informed choice about which hand lens is most appropriate.

Glass versus plastic lens?

The optical lens in a hand lens can be made from glass or plastic – the plastic lenses are generally more affordable and lighter but are of lower optical quality and more difficult to clean. Good plastic hand lenses, such as the Plastic Double Magnifier, are perfect for youth groups and schools.

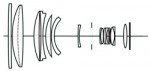

How many optical elements?

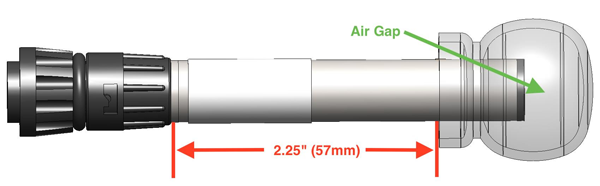

An element is an individual piece of glass within a lens. When you look through a high quality camera lens you will typically be viewing what’s in front of the lens through four to six lens elements, as well as other elements used for focusing and zooming (see image below right).

Hand lenses are constructed with one (singlet), two (doublet) or three (triplet) lens elements. Each element is specially shaped to correct for a particular type of optical distortion so the more elements, the higher quality the image.

Magnification

A 10x magnification hand lens will be more than adequate for most purposes. Higher magnification lenses tend to be harder to use but are very useful for viewing extremely small objects. If you are unsure of which magnification you need, or think you may need several different lenses, you should have a look at the x10 and x20 Duel Singlet Loupe or even the x3, x4 and x5 Triple Loupe.

Lens diameter

Large diameter lenses provide a wider field of view which means that they are easier to use but they are slightly more expensive to produce.

Hand lenses are named like binoculars, with both the lens diameter and the magnification included in the name. e.g. the Opticron Hand lens, 23mm, 10x magnification has a 23mm diameter lens and provides 10x magnification.

Using your hand lens

Finally, a quick note on hand lens technique. To use your hand lens correctly (this is particularly important when using high magnification lenses) hold the lens close to your eye and then either a) move the subject closer to your eye until it comes in to focus or b) move your head (and the hand lens) closer to the subject until it comes into focus. It’s easy with a little practice so don’t get put off if you find a new hand lens difficult at first. Expect to get close up to what you’re examining – it’s quite common to see naturalists crawling around on the ground to get close to a plant they’re identifying.

Keeping your hand lens safe

It can be very hard to find a much-loved hand lens dropped in long grass or woodland. To prevent this traumatic experience, we recommend a lanyard for your hand lens – this has two functions: a) if you have it round your neck you won’t drop it, and b) if you put it down somewhere the bright blue lanyard is easy to spot.

The table below provides a guide to the hand lenses sold by NHBS. More information and specifications of each can be found on the website.

[table id=2 /]

The

The

![Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland] Tommy Karlsson, author of Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Tommy-Karlsson-300x284.png)

![Onychogomphus foripatus description and distribution map from Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242_4.jpg)

![Östergötlands Trollsländor [Dragonflies in Östergötland]](https://media.nhbs.com/jackets/jackets_resizer_large/22/224242.jpg)