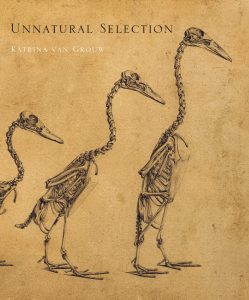

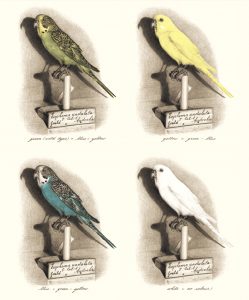

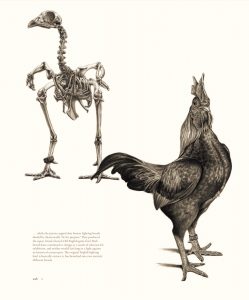

After her incredibly successful book The Unfeathered Bird, Katrina van Grouw has recently finished Unnatural Selection, a beautiful combination of art, science and history. In this book, she celebrates the rapid changes breeders can bring about in domesticated animals. This was a topic of great interest to Charles Darwin, and it is no coincidence that Unnatural Selection is published on the 150th anniversary of Darwin’s book The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.

In this post we talk with Katrina about her background, the work that goes into making a book and plans for the future

![]()

On your website, you write that you always had an interest in natural history, but that your talent in drawing made your teachers push you to pursue an art career, rather than studying biology. Did you ever consider a career as a scientific illustrator, something for which there must have been more of a market back then than there is now? If not, when and how did you decide to start combining your passion for biology with your talent as an artist?

On your website, you write that you always had an interest in natural history, but that your talent in drawing made your teachers push you to pursue an art career, rather than studying biology. Did you ever consider a career as a scientific illustrator, something for which there must have been more of a market back then than there is now? If not, when and how did you decide to start combining your passion for biology with your talent as an artist?

No, I didn’t. There are several reasons for this; some a result of indoctrination, and others, decisions of my own.

There were two revelatory moments which brought art and science together for me and set the path for what was to come. Once when I’d rejected art and was sliding down a greasy pole into oblivion. And another, when I was an art student seeking direction. The first was at a zoo, and the second at a museum, and both were as vivid as a flash of light from the sky.

Even with art and natural history combined in my work, however, it was always in a fine art sense and never as an illustrator. I still don’t really identify with the term. Being an illustrator usually involves working to someone else’s brief and taking instructions from a non-illustrator about how the work should be done. I’m too self-obsessed for that! I lack imagination when it comes to commissioned work and can’t seem to generate much passion for other people’s projects, though I have the greatest respect for people who can do these things. I’m basically just no good at it!

You worked as curator of the bird skin collection of the London Natural History Museum. How did you end up there after an art degree?

You worked as curator of the bird skin collection of the London Natural History Museum. How did you end up there after an art degree?

How I ended up there is quite a long story. I do have a degree in art (two actually) but I also spent many years gaining valuable skills in practical ornithology that were precisely what the NHM needed; a combination of skills that was lacking in all the other applicants for the post.

I’d taught myself to prepare study skins and was good at it. I knew my way around the inside of a bird and had written a Masters’ thesis on bird anatomy (albeit aimed at artists). I was a qualified ringer who’d held an A class ringing permit for many years, which meant that I could age and sex birds accurately and knew how to take precise measurements consistent with other field workers. I’d taken part in ornithological expeditions in Africa and South America, so I had some first-hand experience of non-European birds. I’d worked in other museums. And I was a birder.

It’s a sad fact that one’s education often defines how a person is categorised for the remainder of their life, but self-taught skills, and hands-on experience can be worth far, far more. People often assume that artists can only ‘do art’ and nothing more, and that only people with a science degree are able to ‘do science’. A great many people are able to do both (though fewer questions are raised when it’s a qualified scientist who turns his/her hand to art!)

Your previous book, The Unfeathered Bird, took some 25 years from conception to publication, mostly as you found it very difficult to find a publisher. How did you manage to convince Princeton University Press to publish this book after so many rejections?

Your previous book, The Unfeathered Bird, took some 25 years from conception to publication, mostly as you found it very difficult to find a publisher. How did you manage to convince Princeton University Press to publish this book after so many rejections?

The quick answer is, because Princeton University Press is a publisher of vision and wisdom! (And no, they didn’t pay me to say that).

The full story is that the majority of publishers I approached had entrenched preconceptions about what an anatomy book should be and were unable to envisage anything that wasn’t a highly academic technical manual aimed at a niche audience. The book I had in mind was geared toward a much broader spectrum of bird lovers, including and especially bird artists. Additionally, I wanted it to be beautifully produced and aesthetically pleasing. So it wasn’t so much a problem of not being able to find a publisher, but not being able to find a publisher willing to think outside of the box. To answer the question: I didn’t actually need to convince Princeton –a fortuitous meeting lead to a great collaboration.

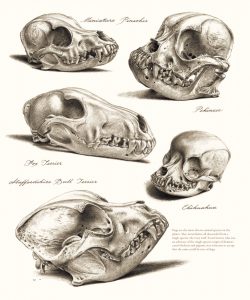

Your response to critics of breeding has been to counter their objection by saying “look at what nature has done to the sword-billed hummingbird!” which I thought was a sharp response. However, an animal welfare advocate might counter this argument by pointing out that natural selection can only push sword-billed hummingbirds so far. If this adaptation – the extension of the bill to retrieve nectar from ever deeper flower corollas – becomes maladaptive it will be selected against. Breeders, however, can select for traits that are maladaptive, because these animals grow up in an artificial environment where they are relieved of the pressures of natural selection. The shortened snouts and breathing problems of short-nosed dog breeds such as boxers come to mind. Obviously, if these traits become too extreme, the animals will not survive until reproductive age, but we can push them into a zone of discomfort and suffering through artificial breeding. What would your response to this be?

Your response to critics of breeding has been to counter their objection by saying “look at what nature has done to the sword-billed hummingbird!” which I thought was a sharp response. However, an animal welfare advocate might counter this argument by pointing out that natural selection can only push sword-billed hummingbirds so far. If this adaptation – the extension of the bill to retrieve nectar from ever deeper flower corollas – becomes maladaptive it will be selected against. Breeders, however, can select for traits that are maladaptive, because these animals grow up in an artificial environment where they are relieved of the pressures of natural selection. The shortened snouts and breathing problems of short-nosed dog breeds such as boxers come to mind. Obviously, if these traits become too extreme, the animals will not survive until reproductive age, but we can push them into a zone of discomfort and suffering through artificial breeding. What would your response to this be?

I’m an animal welfare advocate too. It’s difficult not to be when you keep animals and care for them every day. I too will freely admit that there are exhibition breeds in which artificial selection appears to have gone too far, resulting in health problems or discomfort. I can also appreciate that these problems might have their roots deeply embedded in history and culture and might be difficult to rectify without tearing down systems that would have devastating consequences to the entire fancy.

(Incidentally, the suffering of poultry selectively bred for the commercial meat industry is on a scale many thousands of times greater than the relatively low numbers of extreme pedigree breeds.)

The process of selecting out these physical defects will be a slow one and I think it’s important to support the work of breeders in this task. We can support them by trying to understand more about their world and by ceasing to attack them in gutter-press fashion with pseudo-scientific terms we don’t fully understand.

My book Unnatural Selection isn’t intended to voice personal opinions about animal welfare however. As the title suggests, it’s a book about evolution, based on and elaborating on the analogy that Darwin made between natural and artificial selection. For that reason I’ve discussed selective breeding solely within this evolutionary and historical context. It’s not that I was deliberately avoiding welfare issues; they simply weren’t relevant to the points I was discussing.

You write that the work on Unnatural Selection took six years of full-time work, around the clock. How long do you typically take to complete an illustration? And how do you manage to support yourself during this period, do you have freelance illustrations assignments on the side?

You write that the work on Unnatural Selection took six years of full-time work, around the clock. How long do you typically take to complete an illustration? And how do you manage to support yourself during this period, do you have freelance illustrations assignments on the side?

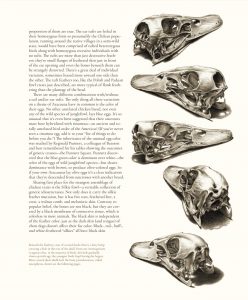

If I’m in-practice I can usually complete a full-page illustration in two or three days. There are 425 illustrations in Unnatural Selection, not forgetting the 84,000 words of text (somehow people always forget the text…). Not to mention thousands of hours’ research and background reading. Working like this is all-consuming, and definitely very unhealthy.

The fact is that non-fiction books taking so long to produce will never, ever, pay for themselves. Luckily Husband works full time, so we don’t actually starve, though I’d prefer to be able to contribute more financially to the household.

I would love to supplement my books with a part time job, but it certainly wouldn’t be illustrating! I dislike illustrating for other authors. I actually get far more pleasure from writing and I’m equally good at it, though this side of me is unfortunately often eclipsed by the artwork.

People talk in airy-fairy terms about the freedom and personal reward of being an artist transcending material gain, but it’s not like that at all. It’s not the actual poverty that’s damaging, but the feeling of inadequacy you get from working so hard, with such integrity, for so long, yet making no money.

The things that make it worthwhile are making those books exist at the end of it all, and having people tell me how grateful they are.

With two books now published by Princeton University Press, you seem to have started a very successful collaboration. How has the reception of this book been so far? Have you received nominations for prizes?

With two books now published by Princeton University Press, you seem to have started a very successful collaboration. How has the reception of this book been so far? Have you received nominations for prizes?

Boy, I’d love to win a prize! It’s still early days yet, so I’m ever-hopeful. To be honest though, I suspect I’m not the sort of person who wins prizes. Prizes seem to be dished out to academics and people whose career has been rather more conventional than mine. Like my books, I rather defy taxonomy and, even though we communicate science exceedingly well, few institutions would be brave enough to award a science writing prize to a self-taught scientist.

That’s not to say that we’re unpopular; quite the opposite. I’m proud to say that The Unfeathered Bird was embraced by a huge range of people: birders, naturalists, painters, sculptors, taxidermists, poets, mask makers, puppeteers, aviators, falconers, bibliophiles, palaeontologists, zookeepers, creature-designers and animatronics-people, academic biologists and vets! The pictures have been used in a trendy Berlin cocktail bar, on Diesel t-shirts, and tattooed onto several people’s bodies, and I get very genuine letters of thanks from all manner of people, from university professors and 12-year old boys and girls.

Unnatural Selection is a far better book than The Unfeathered Bird. It has better art and better science and, unlike The Unfeathered Bird in which the images take the lead, Unnatural Selection is very much led by good scientific and historical text, with the images serving solely to illuminate and enhance what’s being said. Everyone who’s seen it so far says it’s stunning, and the reviews have all been excellent. I hope the scientific community will take it seriously and not dismiss it as merely a quaint and witty book with good pictures. It’s so much more than that.

Will you continue to work on more books in the future? And are you already willing to reveal what you are working on next?

Will you continue to work on more books in the future? And are you already willing to reveal what you are working on next?

In answer to your first question: definitely—though if you’d asked me that toward the end of The Unfeathered Bird I would probably have said no. That book was supposed to have been a one-off, and I’d been looking forward to resuming work as an artist afterwards. However, when the time came I found that I’d moved on. Producing pictures for their own sake no longer ‘did it for me’. Books, on the other hand tick all the boxes: creatively, intellectually; at every level.

It’s important to understand that these are not ‘art books’—they’re not collections of artwork made into a book. The book itself is the work of art, not the individual illustrations. They’re science books nevertheless. For me the challenge is communicating science in the best possible way and finding just the right unique angle for each book. I’m especially proud of Unnatural Selection which I think is the finest and most original thing I’ve ever created.

Unfortunately, large illustrated books take many years to produce so I probably won’t have sufficient time left to bring more than two or maybe three more into existence. After all, I’m no spring chicken.

I’ve already signed a contract with Princeton and begun work on a greatly expanded second edition of The Unfeathered Bird. The new book will have 400 pages (that’s 96 more than the first edition) and will include a lot of new material on bird evolution from feathered dinosaurs (which of course will be unfeathered feathered dinosaurs, if you see what I mean). There’ll be lots of new and replacement illustrations and the text will be completely re-written. The science will be better, but the book will still accessible to anyone and devoid of jargon. However, this shouldn’t put people off buying the original version—the new edition will be virtually a different book.

I’m also intending to write an autobiography/memoir type book focusing on the relationship between art, science, and illustration, and will be looking for a publisher for that. This won’t be illustrated though, so it would be a comparatively quick one!

![]()

Unnatural Selection has been published in June 2018 and is currently on offer for £26.99 (RRP £34.99).