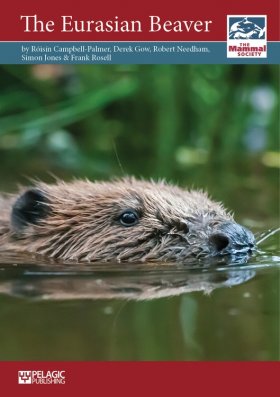

Ecologist Derek Gow (The Derek Gow Consultancy) is the co-author of The Eurasian Beaver, published in January 2015. His involvement with Devon Wildlife Trust’s trial reintroduction and the Tayside beaver reintroduction makes him uniquely placed to discuss the topic of beaver reintroductions in the UK.

How would the presence of healthy beaver populations enhance the UK’s landscape and biodiversity?

How would the presence of healthy beaver populations enhance the UK’s landscape and biodiversity?

In Eurasia and North America beavers are the keystone species around which all other wetland life revolves. Their simple dam building and tree felling activities trigger a whole range of complex changes in their surrounding environments which clearly result in greatly enhanced levels of biodiversity and biomass. In landscapes which are semi-natural the cascade of dynamic changes they produce harbours the potential for breathtakingly spectacular results, such as the return of the black stork. While in highly manipulated, human engineered environments they can literally breathe life back into the land.

You are involved with the Devon Beaver Project, which has created a test environment to see how reintroduced beavers would affect their local ecosystem. Can you tell us more about this project, and what results it has produced so far?

The initial stage of the Devon Beaver Trial was designed to evaluate from ground zero the impact of a beaver family in an enclosed area of wet-woodland of approximately 3ha. Between 2011 and 2015 the beavers created a series of approximately 14 major dam systems on a 200 metre length of a seasonally flowing water course at the northern end of the site. They maintain long dams in the winter when water is abundant and short dams in the summer when water is scarce. At the time of writing their impoundments are capable of retaining approximately 1000 tonnes of water, none of which would have seasonally remained on site without them. The return of the beaver has been accompanied by a proliferation of wildlife. Flowering and other vascular plant communities now abound on site. On warm sunny days meadow browns, marbled whites and a host of other butterflies flit through its open woodlands. Dragonflies and damselflies occur in ever greater numbers while amphibians such as common frogs have increased in numbers fiftyfold. Juvenile common lizards hunt through the deadwood understory while marsh tits, spotted flycatchers, greater spotted woodpeckers, tree creepers and redpolls hunt insects in the trees. Water fowl have moved into occupy environments which formerly did not exist. Red and roe deer jump the perimeter fence to drink in its pools.

It is an absolutely amazing project and a brilliant site.

What does a reintroduction look like in practical terms? Can you break down the logistics of species reintroduction?

Well if you ask the Germans its simple: you get lots of beavers – 40 plus per release, drive along the road, spot a likely location, and let them go. A crude system which works! Reintroductions in Britain are often subject to a large degree of politics, which can be frustrating as this is a species well understood throughout its natural range which simply offers so much. We could do much better. To date, beaver reintroduction has been a haphazard affair with major public spats between those that wish them to remain and those that are opposed – the history of the Tayside and Devon beavers demonstrate this well. Given that this species was last present in Britain outside of our living memory, it is assumed that licensed releases require a scientific demonstration of how this animal will impact a British landscape – as though it will be any different from what our European and American counterparts have already demonstrated. In realistic terms, in Britain an official reintroduction would involve a small number of animals, released into a specific site, with thorough scientific monitoring of impact and public opinion. Though we may take heart that beavers are now back in our landscape, the process to full restoration is likely to be slow and cautious.

What precedent does the approval of the River Otter beaver population set for reintroductions as a wider concept? Are we likely to see lynx roaming wild any time soon?

We need to learn to live with and tolerate beavers before I think we can accomplish anything more adventurous in Britain. If we can’t move forward with reintroducing this charismatic rodent that has such significant impacts on its environment, and can single-handedly do so much to restore our wetlands, then we need to be seriously realistic about our collective ability to accept top predators on this island – no matter how nostalgic or headline grabbing the notion of lynx may be.

What would you say to people who consider reintroduction to be somehow against the natural order of things?

When you consider our contemporary British landscapes and their land-use practices, which are entirely dictated by human activity, they represent little in the way of natural order. In truth they are not ecosystems and we are probably grasping at straws to even describe what’s left as tattered fragments blowing in the wind. Instead we have a wealth of isolated areas of biological richness, generally produced as a result of relict human activities which are difficult to maintain and increasingly vulnerable and fragile. Do we accept that these nature zoos are it, or do we try to foster and encourage a process whereby we change the pattern of the landscape we have made to make it better for people and wildlife alike? Reintroductions, where human activities have caused the past extinction or diminution of a species in Britain, are simply a tool we should employ with competent ease where the circumstances justify its use.

We recently heard the news about the successful litter of kits produced by the River Otter beavers. What did this news mean to you personally?

Brilliant!! It’s been a long time coming. Let’s move on now from these vital but small and isolated pockets of beavers and see the full restoration of this incredible species.

Also available now

Nature’s Architect: The Beaver’s Return to Our Wild Landscapes is the latest book from leading nature writer Jim Crumley. The book explores the natural history of the beaver, and Crumley makes his case in favour of beaver reintroduction.

Nature’s Architect: The Beaver’s Return to Our Wild Landscapes is the latest book from leading nature writer Jim Crumley. The book explores the natural history of the beaver, and Crumley makes his case in favour of beaver reintroduction.