Heathlands are so much more than simply purple carpets of heather. They are ancient landscapes found throughout Britain that support a complex network of inter-related species and an immense diversity of habitats. They also possess a unique human history defined by the struggle between pastoralism and the competing demands of those who seek exclusive use of the land.

Heathlands are so much more than simply purple carpets of heather. They are ancient landscapes found throughout Britain that support a complex network of inter-related species and an immense diversity of habitats. They also possess a unique human history defined by the struggle between pastoralism and the competing demands of those who seek exclusive use of the land.

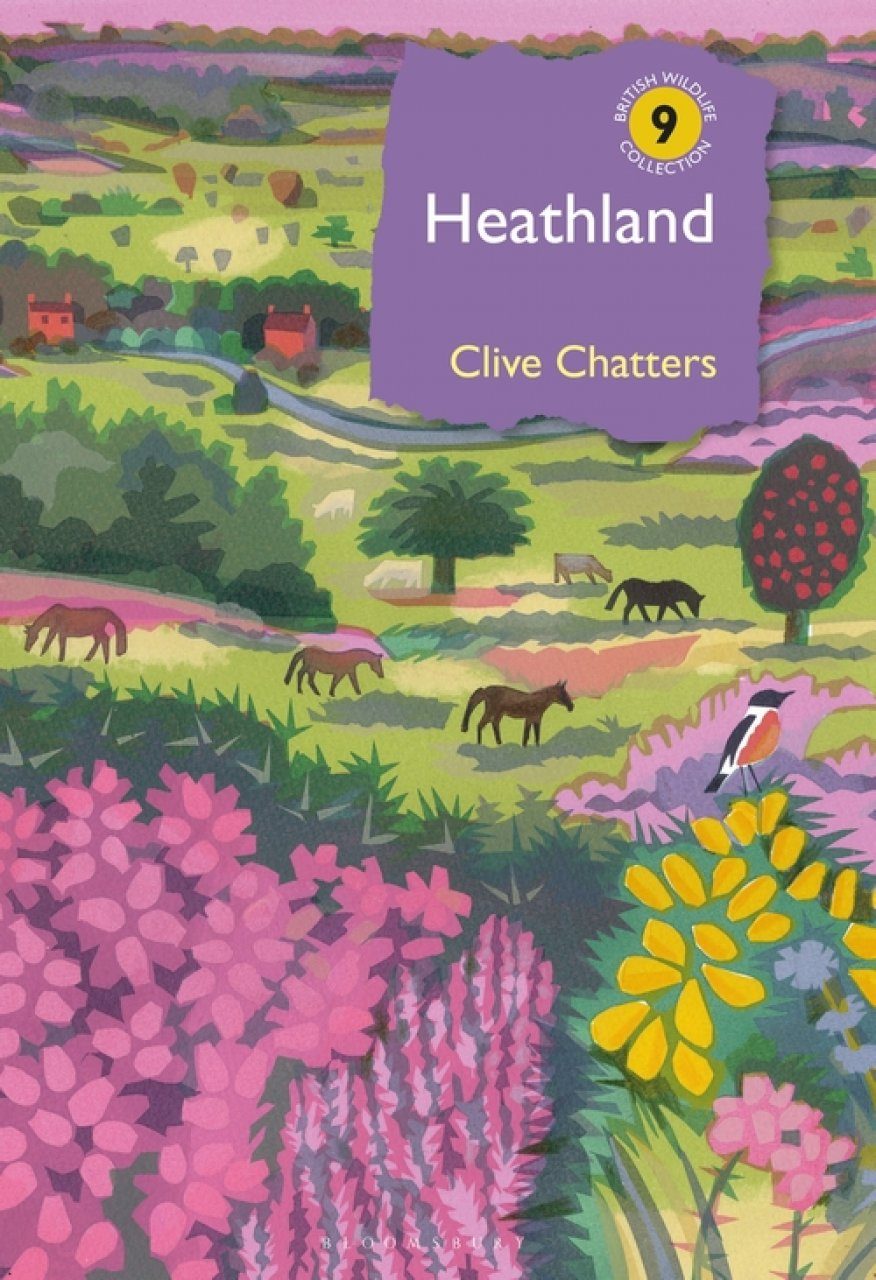

In this latest addition to the British Wildlife Collection, Clive Chatters introduces us to Britain’s heathlands and has kindly taken some time to answer some questions concerning this important habitat.

Heathland might mean different things to different people; how did you go about defining ‘heathland’?

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special.

Heathlands defy ready definition. The diverse places that we call heaths are cultural landscapes which are overlain with the language of ecology. It is unnecessary to reconcile these different perspectives as both traditions offer a path to understanding what makes our heathlands special.

Heathlands are one of a handful of British landscapes that have been recognised by English- speaking people for as long as we have had a written history. Sadly, many of the places that early ecologists were describing had already been depleted of much of their diversity and wonder.

This book seeks to challenge those narrow definitions and to promote an understanding of heathland that would be familiar to our forebears, as well as respecting the experience of modern people whose livelihoods are bound up with the heath.

Literature and historical accounts have addressed heaths: these landscapes can also be found in literary works, in poems and romanticised histories. When did their ecological value start to be recognised?

There is a remarkable body of literature surviving from medieval England, with many references to heathlands. Narrative poems that pre-date the Norman conquest give us an indication of how heaths were viewed by Anglo-Scandinavian story-tellers.

Heathlands at the end of the Tudor period were places where people could gather on the margins of settled society and by the seventeenth century there are the beginnings of natural histories that go beyond the enumeration of commonable livestock or illusory wild beasts. The antiquarian John Aubrey gives an account of a lichen heath in his Natural History of Wiltshire. Herbalist, Thomas Johnson published two accounts of the flora of Hampstead Heath, which include over 120 flowering plants. By tabulating a sample of these records, and ordering them by habitat association, we can gain an insight into the character of a Southern Heath in the early seventeenth century.

Throughout history there has been people who have valued heaths as a source of their livelihood. It was not until the early twentieth century that ecologists started to describe heaths and then it took many more decades before their importance to nature conservation has been expressed by conservationists. In the meantime, we have lost so much of the diversity and wonder in British heaths. What my book sets out to do is explore those riches and consider what has sustained them, where they persist.

What are your primary hopes and fears for the long-term future of Britain’s Heathland?

It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness.

It is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Whilst there are still significant challenges to overcome, we know enough about these habitats to secure their place in the countryside of the future, as an integral part of British culture and home to a wealth of species that occupy ecosystems of immense richness.

If we are to rejuvenate heathland as a commonplace element in the British countryside, then we need to be comfortable with knowing what successful rehabilitation looks like. The wildlife of our richest heaths is the fortuitous by-product of millennia of pastoral farming. Over the span of human history, it has been pastoralism that has provided continuity for ecological processes pre-dating agriculture and reaching back into evolutionary time.

If we are to have working heathland landscapes, with all the advantages they bring, then the pastoralists will need to be properly funded and rewarded.

A successful heathland needs to have scale. Heathlands are landscapes that can be remarkably robust in delivering the multiple objectives that we ask of them, but they must be measured in multiples of square kilometres rather than in tens of hectares. We need not be shy about seeking to create a new generation of heaths that are large enough to serve the needs of nature alongside the ambitions of the modern age.

Heathlands are so much more than ‘just’ heathers: could you summarise their importance for a diverse range of fauna and flora?

Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

Heathlands are a great deal more than just carpets of heathers. A heathland landscape can embrace habitats as diverse as rocks and lakes and bogs, even temporary stands of arable and wartime concrete. The component habitats of a large functioning heathland are naturally dynamic, with species dependant on all sorts of habitat formations, from bare ground to the decaying of cowpats. The great antiquity of heathland ecosystems is reflected in the network of interdependent species, many of which are associated with large herbivores, fire and occasional gross disturbance of the soil. Whilst charismatic birds and reptiles have traditionally claimed the limelight, the biological wealth of the heath is better expressed through its invertebrates, lichen and wildflowers.

Until recently, the State implemented conservation initiatives; this is no longer the case and the withdrawal of central government from practical conservation management has placed greater demands on the work of local government. Has this had a significant impact for heathland?

Heathlands are not capable of sustaining ever-intensifying levels of recreational use, no matter how benignly intended. There are numerous examples of habitats that have been degraded and species that have been lost through the complex interactions of wildlife and informal recreation. Our affection for heathlands is no safeguard against them being loved to death.

Dogs, for example, are ecological proxies to natural predators but are present at much higher densities than would occur in the wild. And large heathland ponds are frequently developed for recreation with dire consequence for wildlife.

It is reasonable for people to expect a choice as to where they can go in the countryside; regrettably, in some heathland regions, the heaths are not used for recreation as a matter of choice but because they are the only greenspaces that are available.

This is your second book in the excellent British Wildlife Collection series; the other being Saltmarsh. After all the work researching and writing that and now Heathland what is next for you? Are there plans for further books, or maybe a well-earned rest?

There are germs of ideas for future writing which I hope will take shape in the next few years. Books are daunting ventures; ‘Heathland’ summarises forty years of study and took three years to write, maybe next time I’ll look at something a little simpler.

Heathland

Heathland

By: Clive Chatters

Hardback | March 2021 | £27.99 £34.99

In this latest addition to the British Wildlife Collection, Clive Chatters introduces us to Britain’s heathlands and their anatomy.

Most of our heaths are pale shadows of their former selves. However, Chatters argues, it is not inevitable that the catastrophic losses of the recent past are the destiny of our remaining heaths. Should we wish, their place in the countryside as an integral part of British culture can be secured.

All prices correct at the time of this article’s publication.