Derek Gow has written an inspirational and often riotously funny firsthand account of how the movement to rewild the British landscape with beavers has arguably become the single most dramatic and subversive nature conservation act of the modern era.

Derek Gow has written an inspirational and often riotously funny firsthand account of how the movement to rewild the British landscape with beavers has arguably become the single most dramatic and subversive nature conservation act of the modern era.

Derek has taken time to answer a few questions about his new book and the role beavers can have in restoring nature.

Could you tell us a little about your background and where the motivation for this book comes from?

I was born in Dundee in a council house. My grandfather’s generation had been farmers but my parents were not. I have always had a huge interest in nature which developed as I grew older. In time I began a career in farming and while aspects of this life were appealing, I became less enamoured with the impact of farming on the natural world and the savage repercussions of its consequence. I read all Gerald Durrell’s books when small, attended his field course on Jersey in 2000 and from that point on, initially as a manger for several wildlife centres focused on native wildlife and then ultimately, on my own farm, began to pioneer opportunities for wildlife restoration.

You have a clear affection for beavers; will a more emotive dialogue help spread the idea of restoring nature to a broader base, or do you think the science will win hearts and minds?

I think it’s a combination of both. You need science to back a case for their sentient restoration on the back of all the credible good they do, but you also need people to feel emotionally linked. They are the most wonderful of creature’s – creators of landscapes which are brim-full of life. They are caring for their offspring and while savagely territorial with other beavers, are commonly as individuals, largely benign. We did appalling things to them in the past and in effort to forge a better future I see no harm in explaining to people just how critical it is that we consider other species as individuals of worth and importance with characters as well.

There are so many organisations involved; some still going, some now inoperative: DEFRA, IUCN, SNH, EN, NCC, CLA etc. How do you manage to reach a consensus across all those organisations, and do you think the voice for restoring nature needs streamlining?

Yes it needs streamlining, but we need to be much bolder and much less deferential. In the commercial world if individuals or organisations perform poorly then they are dismissed or they disappear as entities. In nature conservation we are way too good at ignoring duffers and making excuses for their mistakes. This situation however uncomfortable is simply no good and at a time of ecological crisis potentially fatal. We must be bullish in our approach to progress while still retaining what reasonable allies there are. The pace of restoration should be swift rather than slow. There is no reason whatsoever for delay.

The activities of beavers such as: felling trees and potentially flooding arable land sound quite alarming to a lot of people. How are those issues addressed when proposing to reintroduce beavers?

Simple. We published a management handbook in 2016 which you chaps help sell and promote. Beavers are a very well understood species in both continental Europe and North America all we need to do is co-opt the sensible programmes of management and understanding which have been applied there to here, stop gibbering and making up excuses and move on. There is nothing they do which we can’t counteract if we wish to do so. A wider programme of education to promote better understanding is an essential first step.

Beavers seem to be a benchmark to define our future relationship with wild creatures. Does your campaign stop at beavers, or would you like to see other ‘lost’ species reintroduced to Britain?

I think that lynx should be restored with reasonable haste if living space which is suitably large with an adequate abundance of prey sufficient to maintain a viable population exists. I think wildcats must be restored in England and in Wales. Other candidates would be species like the great bustard, wild boar, golden, white tailed eagles and common crane; in a wider range, the burbot, black stork/more whites, vultures and many other amphibians, reptiles and insects. I think a dialogue should begin about learning to relive with the wolf now. If we want to have future forests which the deer can’t destroy we will need this predator very much.

Does Brexit and the eventual demise of the Common Agricultural Policy offer any hope for a more nature sensitive approach to farming in the UK?

Yes it does. We can do it our way now but we must recognise that very much good has come from the EU habitats directive and that our way should seek to exceed and surmount this legislation and not just become a tawdry box ticking exercise in excuse manufacturing and prevarication.

With beavers now established in Devon on the River Otter, how do you see that project developing in the next five years?

The beaver population there will expand for sure to number many 100’s over time. Many other rivers should become the focus of further reintroductions as a result of the excellent field work and research carried out on the Otter by a broad range of partnership bodies. The project and its results demonstrate quite graphically that beavers are entirely tolerable in a modern cultural English landscape with a degree of low level intervention and that their engineering activities enable an abundance of other wildlife to flourish.

Have you any projects you are currently involved in, or planning that you can tell us about?

Together with a range of other organisations I am working to form a wood cat project which will culminate in the reintroduction of the wildcat in Devon. The old English name was the wood cat and those of us involved think therefore that this is a more appropriate escutcheon. Next year I will be releasing white storks on my farm and rewilding over 150 acres of land which I own. In March 2021 I will complete work on a new book for Chelsea Green titled The Hunt for the Iron Wolf which will detail the history of this species in the UK.

Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways

Bringing Back the Beaver: The Story of One Man’s Quest to Rewild Britain’s Waterways

By: Derek Gow

Paperback | January 2022

Derek Gow’s inspirational first-hand account of beaver reintroduction across England and Scotland.

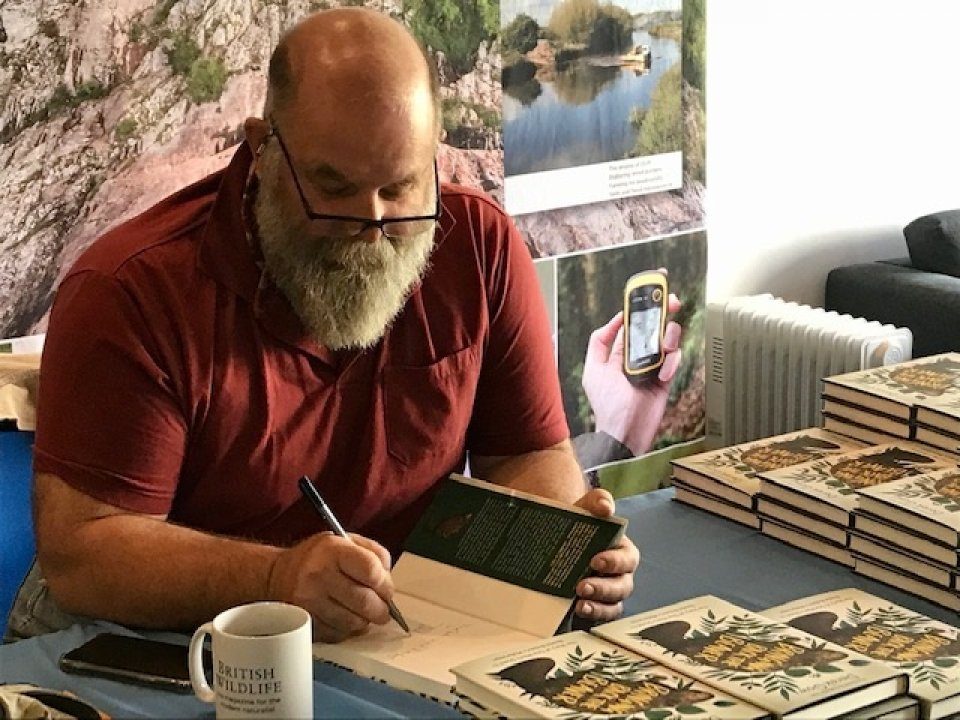

Derek Gow is a farmer and nature conservationist. Born in Dundee in 1965, he left school when he was 17 and worked in agriculture for five years. Inspired by the writing of Gerald Durrell, all of whose books he has read – thoroughly – he jumped at the chance to manage a European wildlife park in central Scotland in the late 1990s before moving on to develop two nature centres in England. He now lives with his children, Maysie and Kyle, on a 300-acre farm on the Devon/Cornwall border which he is in the process of rewilding. Derek has played a significant role in the reintroduction of the Eurasian beaver, the water vole and the white stork in England. He is currently working on a reintroduction project for the wildcat.

Interesting interview. I’d like to meet this guy. I have some property in West Virginia, USA, 32 acres of former cow pasture and woodland, all under conservation easement. The previous owner had built two ponds and used lethal means to control the beaver who wandered up from the Cacapon River, 200 meters away. I continued to fight them by breaking up their dams and lodges but it was pointless. I didn’t want to kill them and live trapping and relocation wasn’t practical; nobody wanted them. So one day I had an epiphany. I concluded that a beaver’s vision of what a pond can be was much more highly evolved than mine. So I decided to collaborate with them. I now have 3 additional ponds and the former pasture is being transformed into a vast wetland. They have also built another large pond on other property between me and the river. So far the neighbors have been pretty tolerant; the main opposition comes from my own wife who sees only destruction and doesn’t buy into my long term vision of the emerging meadow. Many magnificent trees have been felled, or girthed and left to die, presumably to open up the canopy to allow new growth. That objective is thwarted however by an overabundance of deer who graze the forest floor continuously in search of seedlings, preventing natural regeneration. The hunters can’t seem to reduce the population to the level needed, and don’t particularly want to. So I’ve taken to placing fenced in deer exclusion circles in select locations to allow new growth to take hold. What is desperately needed are predators, for deer and beaver too. We have a few coyotes but they are viewed as evil and killed on sight. We also have a few black bear which are said to predate on beaver but no evidence of that yet. Wolves and mountain lions would be helpful but not holding my breath on that happening any time soon. For now, I’ll just keep collaborating and hope I can find a new owner who will want to continue the program.