This tale of rat catchers, crumbling buildings and back alleys delves into the complex linkages between humans and rats, questioning why some animals are accepted while others are cast aside. Joe Shute follows the course of this intricate relationship through history, from those in the trenches to the present day, where an estimated ten million rats live in Britain alone.

This tale of rat catchers, crumbling buildings and back alleys delves into the complex linkages between humans and rats, questioning why some animals are accepted while others are cast aside. Joe Shute follows the course of this intricate relationship through history, from those in the trenches to the present day, where an estimated ten million rats live in Britain alone.

Joe Shute is an author and journalist who has a keen passion for the natural world. He is the long-standing author of The Daily Telegraph‘s Saturday ‘Weather Watch’ column, is currently a post-graduate researcher at Manchester Metropolitan University and lives in Sheffield with his wife and pet rats.

Joe Shute is an author and journalist who has a keen passion for the natural world. He is the long-standing author of The Daily Telegraph‘s Saturday ‘Weather Watch’ column, is currently a post-graduate researcher at Manchester Metropolitan University and lives in Sheffield with his wife and pet rats.

We recently had the opportunity to speak to Joe about his book, including his most unexpected lines of enquiry while writing Stowaway, how his own relationship with rats has changed over time, what he plans to do next and more.

What initially drew you to focussing on rats for this book?

I am particularly attracted to the less fashionable corners of nature writing, I suppose. In particular I have a soft spot for scavengers, of which rats are obviously the greatest of them all. I find it fascinating that wild rats are creatures which have adapted and thrived in our shadow over centuries of human history and yet we still don’t know much about them. I wanted to unpick the rat stories and mythology and folklore attached to rats and see them as an animal in their own right. Because the history of rats is so bound up in our own, I also hoped that focusing on rats would help change my understanding of how humans interact with the world.

What were some of the unexpected lines of enquiry the writing of this book opened for you?

I knew about the intelligence of rats beforehand but until I started writing the book I hadn’t appreciated the complexity of the inner lives of rats. Numerous studies have shown that rats feel empathy, regret, possess the power of imagination and even enjoy dancing. I also hadn’t appreciated until writing the book how little is known about rats in the wild. Despite being such a familiar animal, we really have little idea about the size of rat populations or exactly where and how they live in cities. Also, I hadn’t fully appreciated just how clever rats are. I visited a project in Tanzania where rats are taught to detect landmines. In the US, scientists have even taught rats how to drive cars.

Rats have pretty bad PR and this book does an illuminating and erudite job of portraying them with a nuanced and sympathetic appreciation. Why is it important that we scrutinise our relationship with rats?

It’s important to redress our relationship with rats because I believe we are entering a new era of history alongside them. The 20th century was marked by a ‘war on the rat’ with countries committing huge resources to eradicate populations with mostly limited success. This has also had a terrible impact on the natural world, with toxic rodenticides poisoning animals throughout the food chain. This is now changing and various cities such as Paris and Amsterdam are asking whether we might be able to better co-exist with rats. In the UK and elsewhere greater restrictions are also being placed on the indiscriminate use of rodenticides. There are certainly settings where rats are destructive and cause great harm, for example in important seabird colonies where they can devastate nesting populations or indeed when living in someone’s house. But why should they not share our parks and gardens with us?

What are some ways in which rats, and our misconceptions of them, hold mirror up to our own behaviours?

I argue in the book that rats thrive where humanity has failed. Industrial farming, where wildness and natural predators have been lost and monoculture of crops exist, provide the ideal conditions for rats. Similarly in urban areas rats flourish among poor sanitation and low quality housing stock and lots of litter. War, waste and a devastated natural environment are all places where you will find rats. If we address these very human problems and behaviours then rat populations will automatically be kept more in check.

What are your hopes for what rat appreciation can offer us?

I think an appreciation of rats can offer all of us a different perspective on how we interact with nature. When you look at a rat out foraging for food and put aside the cultural baggage attached to it, you see a supremely adaptable creature that can also be very cute!

How has your own relationship with rats changed throughout the process of researching and writing this book?

I started writing this book as someone with an innate fear of rats. Once I started interrogating this, however, I came to realise that so much of this is cultural – the books I read as a child and urban myths about rats which we all grow up with. To conquer my fears I adopted pet rats, Molly and Ermintrude, who revealed to me so much about the inner lives of rats and are the little beating hearts of my book. So much so in fact that I dedicate Stowaway to them.

Finally, are you currently working on any other projects that you can tell us about?

I am currently based at Manchester Metropolitan University’s Centre for Place Writing where I am undertaking a research project on rivers – specifically a lost urban river called the Irk in Manchester. I am doing a lot of work with communities, running writing workshops to connect people to the river and the urban flora and fauna which flourishes there. Unsurprisingly, there are a lot of rats along the Irk, but Kingfishers, Dippers and Grey Wagtails too. It is exactly the sort of contested and overlooked environment rich in human history which I love writing about and where I always feel most inspired.

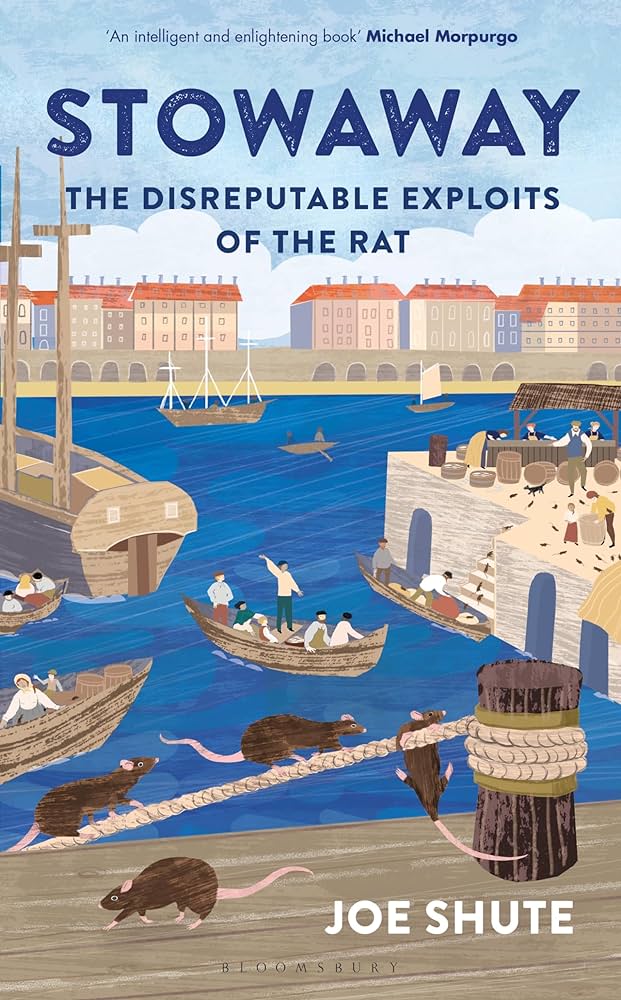

Stowaway has been published by Bloomsbury and is available via our online bookstore.