In order to celebrate Dragonfly Week (13th – 21st July 2019), we interviewed Dave Smallshire, the renowned dragonfly expert and co-author of the excellent Britain’s Dragonflies field guide. Dragonflies and damselflies form the order Odonata and are some of our most iconic insects, with a fascinating life cycle. Damselflies are weaker fliers than dragonflies and have four almost equal length wings that they usually fold up when at rest.

Dragonflies have shorter hind wings and tend to keep their wings out when at rest. Primarily associated with glittering, iridescent glimpses at ponds and wetlands, dragonflies actually spend the vast majority of their lifetime (up to five years) as nymphs in rivers and other water bodies. Both the adult and nymph forms are ferocious predators. Adults are able to move each of their four wings independently and have exceptional vision, giving an astonishing aerial ability that allows them to select a single insect from a swarm. Meanwhile the nymphs are able to jet propel water behind them and use their extendable hinged jaw (labium) to capture prey at lightning speed.

Dragonfly week is organised by the British Dragonfly Society and offers a range of activities designed to celebrate these amazing insects, including the Dragonfly Challenge where you can search for six species and submit your records to the BDS.

Interview with Dave Smallshire by Nigel Jones

1. Could you tell us a little about your background and how you got interested in dragonflies?

As a child I have fond memories of playing around water: dipping into ponds and canals and later fishing (without much success). As a teenager, birds became a passion (they still are), but other things with wings began to attract my attention, notably butterflies and dragonflies. Working in an agricultural entomology department in the 1970s, I was conscious that insect identification keys were useless in the field and it wasn’t until half-decent field guides appeared that I really got to grips with dragonflies and had seen most species by the mid-80s. Soon after, my colleague Andy Swash and I started leading a long series of weekend courses for the Field Studies Council in Surrey/Sussex. When Andy and Rob Still began producing the first of the WILDGuides ‘Britain’s Wildlife’ series, it was a natural progression for us to start work on a field guide to dragonflies.

2. Can you give a brief insight into the time and work that goes into producing a field guide such as Britain’s Dragonflies?

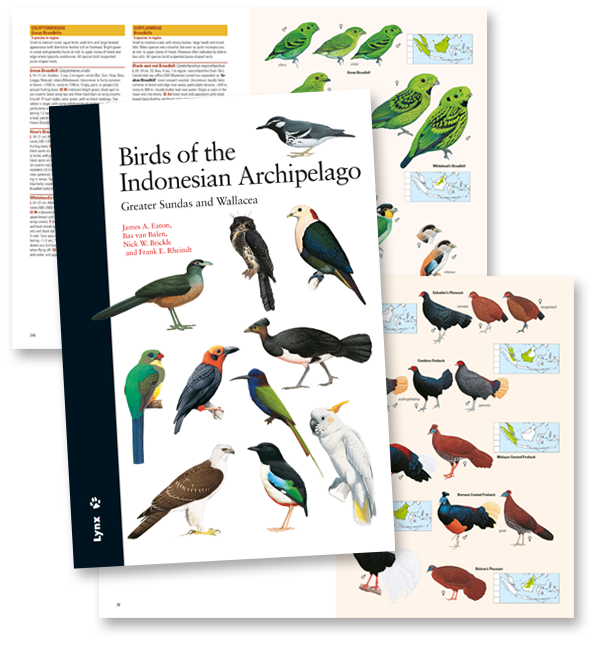

First and foremost, writing and producing such a complex book as Britain’s Dragonflies takes twice as long as you think it will! In addition to drafting all the text, we had to source all the images, which for the first edition (2004) meant viewing hundreds of slides and scanning the best. For subsequent editions, it’s been equally laborious to search the internet and choose the most suitable from many thousands of digital images. Then we had to get permissions and high-resolution files from the photographers. I spent many days with Andy editing the text so that it is absolutely clear and concise – not an easy task! On the publication side, Rob Still was guided through his production of both the illustrations and the amazing photomontages. It’s been hard work, but a real honour to be able to be involved in producing one of the best series of field guides available anywhere.

3. Dragonflies are iconic and familiar insects; how are they faring in terms of population numbers and distribution in the UK?

Until recently, we only had occasional atlas maps to show changes in range, but the British Dragonfly Society, in conjunction with the Biological Records Centre, has worked on a method to use ad hoc records from observers to produce national trends using occupancy modelling. We knew that climate change was aiding northerly spread of some species within Britain and colonisation attempts by species from continental Europe (which makes for exciting times to be out watching dragonflies), but we had little objective information on how our ‘resident’ species were faring. The latest analyses support the obvious increases in species such as Migrant Hawker and colonisers such as Small Red-eyed Damselfly, but also much less obvious decreases in ‘northern’ species such as Black Darter. There seem to be more winners than losers, but next year will see a full analysis for a State of Dragonflies 2020. The generally improved water quality and increase in the extent of wetland creation has no doubt helped many species – a general picture which is in stark contrast to the fortunes of other insects, and wildlife in general.

4. What actions could people take, either within their gardens, or in the wider community to help maintain or increase dragonfly numbers?

In gardens, the obvious answer is to dig a pond – I have two in mine, and they are a constant source of pleasure! Supporting the creation and ongoing management of wetlands in general is also important, so supporting local and national conservation bodies is a good thing. It’s also very important to gather records of dragonflies and help to monitor them, and everyone can help by submitting their sightings (the BDS website gives information on how to do this, as well as how to create a pond for dragonflies).

5. What was your most surprising discovery whilst researching Britain’s Dragonflies?

I have been astonished at how many images on the internet and in social media are misidentified. Even the experts get it wrong sometimes! Take care not to believe everything, and of course buy a good identification guide to help ….

6. What is the biggest challenge when studying dragonflies in the field?

That’s hard to pin down, because I’m aware of so many potential pitfalls! Correct identification is fundamental. Finding out where to see the scarce species to expand your skills is hard, but easier with modern communications. Dragonflies are wary and not easy to approach, so close-focus binoculars and/or a camera are vital – the advent of good quality digital cameras has been a huge benefit. I’ve used a sequence of zoomable Lumix ‘bridge’ cameras over the last 10-15 years to help study wildlife of all kinds, both in the field and back at home. The British weather can be challenging too: a warm, sunny day makes all the difference!

7. Have you got any future projects planned that you can tell us about?

Andy and I have been working for about five years on Europe’s Dragonflies – which is now close to completion and is due for publication next spring. Like all the WILDGuides books, it’s based around high-quality images – in this case over 1,100 of them! It will be presented in a similar way to Britain’s Dragonflies but cover an extra 77 species.

Britain’s Dragonflies by Dave Smallshire and Andy Swash is available as part of our Field Guide Sale. For more reading on Dragonflies & Damselflies, browse our Odonata books

Britain’s Dragonflies: A Field Guide to the Damselflies and Dragonflies of Britain and Ireland

Paperback | August 2018

Focuses on the identification of both adults and larvae, highlighting the key features.

£12.99 £17.99

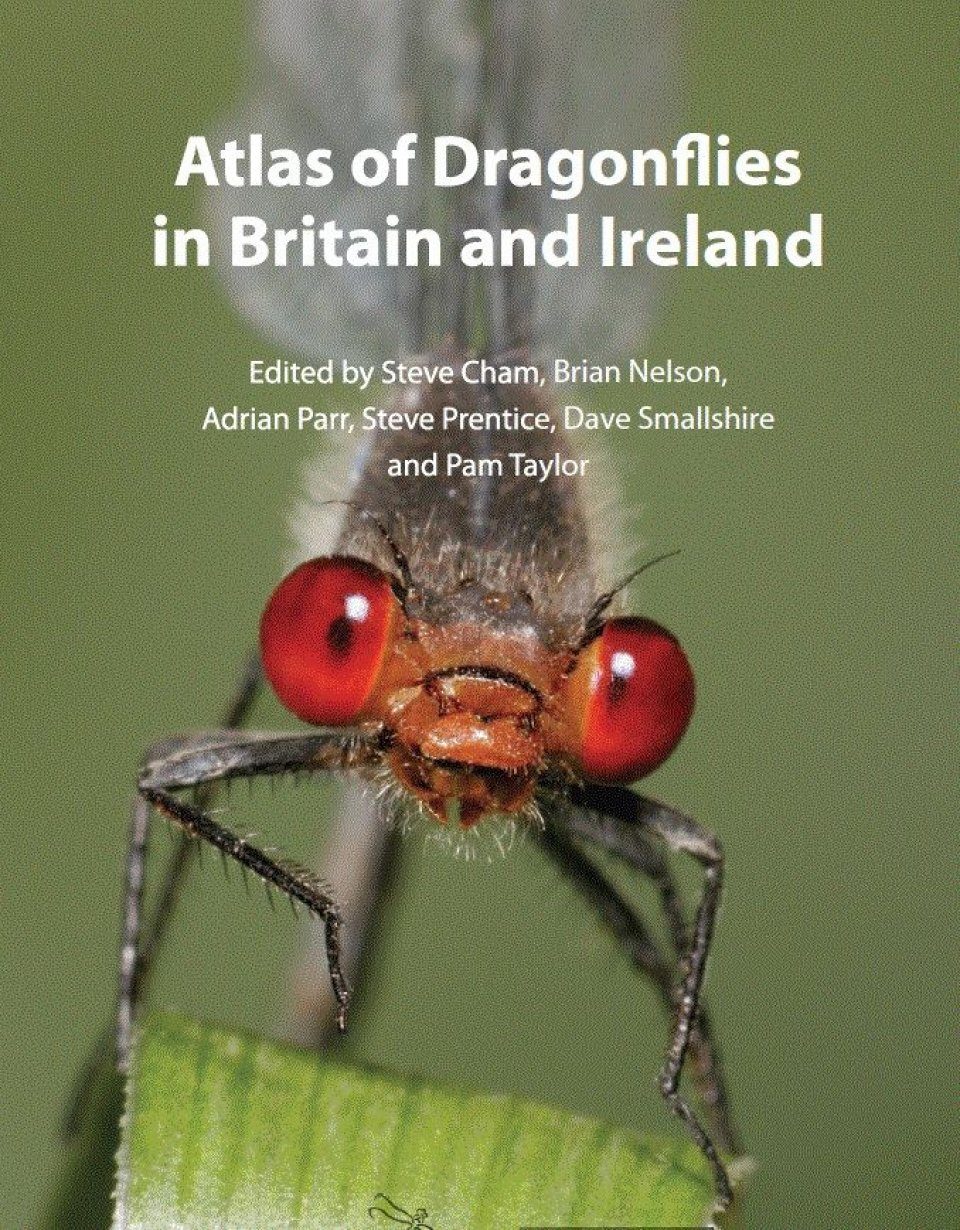

Atlas of Dragonflies in Britain and Ireland

Hardback | May 2014

Represents five years work by volunteers and partner organisations to map the distribution of damselflies and dragonflies in Britain and Ireland

£28.99

Our top picks for observing dragonflies in all their life cycle stages

Opticron Discovery WP PC Binoculars

-

-

- Free shipping for this item

- Great value waterproof binoculars

- Ideal for close focus work

£169

-

-

-

-

-

- 1.9m close-focus with 10 x 50 model

- 30-year warranty

- Entry-level binoculars with all-round performance

-

£289

Professional Hand Net with Wooden Handle (250mm Wide)

Professional Hand Net with Wooden Handle (250mm Wide)-

-

-

-

- Sturdy yet light and easy to use

- Available in a variety of mesh sizes

- Conforms to Environment Agency specification

£61.99£62.94

-

-

-

This kit contains everything you need to collect freshwater aquatic life in one easy package. £31.99

£38.15 -

-

-

-