September is upon us with morning mists and a slight chill in the air… it must be mushroom time! Around this time of year, books on mushroom identification and natural history appear with almost as much certainty as the fungi themselves. Two of our favourite mycologically-minded authors, Peter Marren and Geoffrey Kibby, give some useful and interesting tips for the keen mushroom hunter.

September is upon us with morning mists and a slight chill in the air… it must be mushroom time! Around this time of year, books on mushroom identification and natural history appear with almost as much certainty as the fungi themselves. Two of our favourite mycologically-minded authors, Peter Marren and Geoffrey Kibby, give some useful and interesting tips for the keen mushroom hunter.

(Note: we cannot stress strongly enough the caution with which you should approach mushroom identification. Some mushrooms are edible, but some are deadly, and identification can be very difficult. As Geoffrey Kibby says below, if in doubt, throw it out!).

First up is Peter Marren, whose forthcoming book, Mushrooms, is the first in a new series of natural history publications, the British Wildlife Collection

First up is Peter Marren, whose forthcoming book, Mushrooms, is the first in a new series of natural history publications, the British Wildlife Collection

Peter Marren’s tips on mushroom identification for the beginner

There are an awful lot of fungi – 2,400 species in the latest field guide and that’s just the larger ones. Fortunately, perhaps, most of them are rarely seen. There are only about a hundred really common ones, and they are the ones you need to know.

- Forget about the ‘little brown fungi’ for now. Try getting to know an accessible group such as the waxcaps or the boletes, or the puffballs and their ‘relatives’. It will teach you a lot about the differences between species and the places to look for them.

- Join a fungus foray organised by your local fungus group or wildlife trust, or, better still, attend a weekend course at a field centre. Direct contact is better than books.

- Picking mushrooms does no harm. They are not plants but the fruit bodies of an organism living in the soil or in wood. Apples on the tree, as it were. And you will need to bring back specimens of fungi that are impossible to identify in the field.

- Gathering and cooking wild fungi is great fun, especially as shared fungus feast. But never eat any that you cannot identify with confidence. There are a lot of poisonous fungi out there.

- For fungi an x20 magnification hand lens is useful. At some point the dedicated forayer will need a microscope, but that, as they say, is a whole new ball park. Or playing field, as they are also known.

Peter Marren on recommended books for mushroom identification…

There are not many read-through books about fungi. I enjoyed Patrick Harding’s Mushroom Miscellany, a series of short chapters on all aspects of fungi, and the New Naturalist volume Fungi by Brian Spooner and Peter Roberts is all-embracing and thorough, but not for the faint-hearted. From Another Kingdom, published by the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh is an informal seminar on matters mycological, including ‘fungal monsters in science fiction’. The best field guide in my opinion is still Marcel Bon’s Mushrooms & Toadstools, first published back in 1987, although it needs updating. Paul Sterry and Barry Hughes’ Collins Complete Guide to British Mushrooms and Toadstools has the best colour photographs.

…and on his new book, Mushrooms

Mushrooms is my personal take on the world of fungi in Britain, about the pleasures of searching for mushrooms and toadstools, and why they matter. I have written it as a narrative, in current TV parlance as a ‘journey’, beginning with the extraordinary diversity of fungi and the ways in which they exploit the natural world to the history of the fungus foray and the controversy over gathering wild mushrooms for the pot. In the process I zoom in on the nature of names, both Latin and English, at the places which hold the greatest diversity of fungi, and our attempts to conserve rare and vanishing fungi. It is, I hope, a refreshing and amusing look at this ‘third world’ of life, written without jargon and in lively style. I hope it can be read with pleasure by anyone. It is full of lovely colour photographs.

Next up, Geoffrey Kibby, whose new photographic identification guide to the Genus Amanita is the fourth in a series of full colour fungi identification monographs, and is out now. In the following article Kibby discusses the finer points of mushroom identification:

Next up, Geoffrey Kibby, whose new photographic identification guide to the Genus Amanita is the fourth in a series of full colour fungi identification monographs, and is out now. In the following article Kibby discusses the finer points of mushroom identification:

The joys and tribulations of fungus identification

Firstly, let’s be quite clear: there are an awful lot of fungi! Just including those generally referred to as the larger fungi – those just a few millimetres across all the way up to species that can reach a metre or more – there are around three thousand species recorded in Britain.

Whether we call them all mushrooms, as the Americans tend to do, or toadstools as we often do in Britain, they form a huge and amazing array of species. The terms mushroom and toadstool are of course very vague with no actual specific scientific meaning, encompassing both edible and poisonous species. With such a large number of species to choose from, identification can be both difficult and frustrating, and if edibility is a factor then obviously getting a correct identification is even more important; a mistake can be, and sadly has often been, fatal.

General field guides are the usual starting point for most amateurs just starting out in mycology (the proper term for the study of fungi) but there is an obvious problem here: the number of species included. Many guides have just a few hundred species that may not cover enough of the species you will find. More comprehensive ones usually have about 1000 to 1500 species and are accordingly more useful. The largest guide yet produced (Collins Fungi Guide by Stefan Buczacki with beautiful watercolour paintings) has around 2,400 species, but that does not of course guarantee that you will produce a correct identification. Indeed too many choices might be as confusing as too few. Then there is the choice of whether to get one with photographs or paintings (both have their different advantages).

Many species can only be distinguished with certainty by using a microscope to examine their spores and other microscopic structures, or by the application of specific chemicals to produce colour reactions. More technical monographs are needed for these.

A field guide can only take you so far and show you a representative sample of a particular species. Fungi vary much more than most organisms and you will need to learn them in all their many and varied forms before you can confidently say you know a species well. The best way to learn is to get a good guide and then take it along on an organised fungal walk (or foray as they are usually called). Here you will usually be led by an experienced expert who can show you first hand the important features of each species as well as their particular ecology. The latter can be vital in fungus identification. Many fungi grow in association with specific trees or other plants and knowing this can help you to identify or even predict the species you may find.

By going on regular fungus walks, or perhaps joining a longer course over a weekend or a week you will gradually learn to recognise the commonest species which you will see on almost every walk and start to learn some of the more uncommon species also. Almost every county has a mushroom group and there are also larger, country-wide mycological societies such as the British Mycological Society or the Association of British Fungus Groups. These organisations can put you in touch with your local group as well as organising forays and workshops of their own and producing useful publications. The journal Field Mycology, which I edit for the BMS, is aimed at the beginner all the way to the specialist and mainly deals with larger fungi.

Comparing the actual fungi you find with the photos or paintings in your field guide will soon show the value of owning more than one guide. Each guide may have a different list of species and some will have better illustrations of a particular species than another. Most mycologists soon build up a small library of picture books! Using a digital camera to photograph specimens or trying your hand at making paintings of them and building up your own catalogue of illustrations is highly recommended also. Once you are more confident of the commoner species then there are a number of more specialist works, usually dealing with a specific group of fungi and this is often the best way to really make progress, by concentrating on a particular group which you find especially attractive or interesting.

I would certainly recommend the boletes as an ideal group to begin with. They are often large, very brightly coloured and with good field characters and include a number of excellent edible species. Almost all the species can be identified in the field with a little experience and a good reference work. After 48 years of studying fungi the boletes remain among my favourites and many other mycologists will say the same. The book on boletes which I have produced, British Boletes, aims to provide easy to use keys based mainly on field characters and photographs of the vast majority of the British species. My books tend to focus on the most widely studied and popular groups of fungi. Hence I have titles covering Russula (The Genus Russula in Great Britain), Agaricus (The Genus Agaricus in Britain) and my most recent work The Genus Amanita in Great Britain. All are available from NHBS. Further titles will be forthcoming in the next few months, in particular one on the genus Lactarius, commonly called Milkcaps and further down the road an illustrated field guide to 1200 species of larger fungi.

I would certainly recommend the boletes as an ideal group to begin with. They are often large, very brightly coloured and with good field characters and include a number of excellent edible species. Almost all the species can be identified in the field with a little experience and a good reference work. After 48 years of studying fungi the boletes remain among my favourites and many other mycologists will say the same. The book on boletes which I have produced, British Boletes, aims to provide easy to use keys based mainly on field characters and photographs of the vast majority of the British species. My books tend to focus on the most widely studied and popular groups of fungi. Hence I have titles covering Russula (The Genus Russula in Great Britain), Agaricus (The Genus Agaricus in Britain) and my most recent work The Genus Amanita in Great Britain. All are available from NHBS. Further titles will be forthcoming in the next few months, in particular one on the genus Lactarius, commonly called Milkcaps and further down the road an illustrated field guide to 1200 species of larger fungi.

Geoffrey Kibby’s top tips for safe mushroom identification

Many people come into mycology via a desire to try eating something a little more exotic than the shop bought mushroom. There are many edible species and they can have tastes and textures quite unlike the cultivated species. Hunting for edibles can be a wonderful experience but there are several rules to follow if your hunt is to have a happy outcome:

- Make sure you are allowed to collect, many woodlands or parks have restrictions on picking.

- Obey any local rules on how many you can pick and try to leave some for others to admire, don’t ‘vacuum’ the woods of everything you see.

- Collect only specimens in good condition; old or rotten specimens will not make a good meal and can cause serious stomach upsets.

- MOST IMPORTANT OF ALL: you must be absolutely sure of your identification, some mushrooms are deadly and a mistake can quickly become fatal. If you are a beginner then always get the advice of an expert. Stick to a few, unmistakable species. IF IN DOUBT, THROW IT OUT.

- Always keep aside a specimen of anything you collect to eat and if it is a species you have not eaten before then sample just a little—even good edibles can cause upsets in some people (many people can’t eat strawberries or nuts for example).

Mycology, or mushrooming, can appeal on many levels, from the simple pleasure of seeing strange and wonderful organisms to the intellectual challenge of trying to identify them and understand their intricate life cycles. But the starting point is, and always will be, a good book!

And finally… hand lenses to help with mushroom identification

Last week we published a blog post with advice on purchasing a hand lens, plus a useful comparison chart showing the various lenses you can buy from NHBS.

Read The NHBS Guide to Buying a Hand Lens

This summer, NHBS customer Professor Graham Martin tested the functionality of his Bushnell X-8 trail camera, a great entry-level trail camera for anyone interested in capturing footage of their local wildlife. Trail cameras aren’t just for night snaps – they work night and day using either the trigger function (1 sec for the Bushnell X-8), where the movement of the animal activates the camera’s trigger, or with a time lapse function, where it takes photos at a defined interval (from 1 – 60 minutes).

This summer, NHBS customer Professor Graham Martin tested the functionality of his Bushnell X-8 trail camera, a great entry-level trail camera for anyone interested in capturing footage of their local wildlife. Trail cameras aren’t just for night snaps – they work night and day using either the trigger function (1 sec for the Bushnell X-8), where the movement of the animal activates the camera’s trigger, or with a time lapse function, where it takes photos at a defined interval (from 1 – 60 minutes). Graham has a very warm compost heap which is where these two photos were taken, and he had spotted the grass snake basking – it was too quick for the trigger (0.7 seconds), but he managed to snap it using the time lapse.

Graham has a very warm compost heap which is where these two photos were taken, and he had spotted the grass snake basking – it was too quick for the trigger (0.7 seconds), but he managed to snap it using the time lapse.

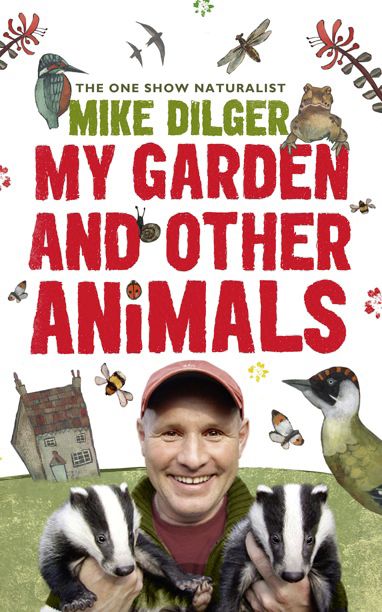

Mike Dilger – enthusiastic naturalist, freelance presenter and author of

Mike Dilger – enthusiastic naturalist, freelance presenter and author of  In terms of high points, there were simply too many to recount – you’ll have to read the book to uncover them all! The meadow stood out as a stunning success, and in addition to turning up a wide variety of wild flowers, enabled me to add grassland butterflies, like ringlet and gatekeeper, to my garden tally. The simple of addition of a pond resulted in an incredible six species of damselfly and dragonfly laying their eggs into the water. With plenty of food also permanently on offer for the birds, a grand total of 61 species were recorded visiting the garden throughout the year. With foxes and badgers all regular visitors, the biggest surprise of all was the brief appearance of an otter in the brook at the bottom of the garden, which I was lucky enough to spot early one morning whilst listening to the dawn chorus! (see picture – right)

In terms of high points, there were simply too many to recount – you’ll have to read the book to uncover them all! The meadow stood out as a stunning success, and in addition to turning up a wide variety of wild flowers, enabled me to add grassland butterflies, like ringlet and gatekeeper, to my garden tally. The simple of addition of a pond resulted in an incredible six species of damselfly and dragonfly laying their eggs into the water. With plenty of food also permanently on offer for the birds, a grand total of 61 species were recorded visiting the garden throughout the year. With foxes and badgers all regular visitors, the biggest surprise of all was the brief appearance of an otter in the brook at the bottom of the garden, which I was lucky enough to spot early one morning whilst listening to the dawn chorus! (see picture – right)

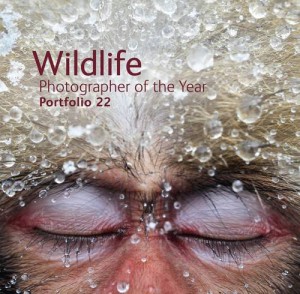

Your photograph, “The assassin”, won the Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2011, Behaviour: Birds category last year. What draws you to birds as a subject in particular?

Your photograph, “The assassin”, won the Wildlife Photographer of the Year 2011, Behaviour: Birds category last year. What draws you to birds as a subject in particular?