Michael Scott is a nature writer and cruise ship speaker who has had an interest in botany since his undergraduate studies at Aberdeen University. His latest book, Mountain Flowers, is an extensive and engrossing survey of Britain’s montane flora. Michael expands on the story of Diapensia (see below) in the August 2016 issue of British Wildlife.

Tell us about the book and who might find it interesting.

I suppose it’s aimed mostly at people who already have some general interest in the wild flowers of Britain. Perhaps they already know something about the flora of lowland areas but don’t quite know where to begin seeking out the more elusive species that grow at higher altitudes in the British mountains. The book describes the key places to visit and some of the characteristic species at each site. It also describes the ecological requirements of each species, and I’d really hope that will encourage people to explore more widely in the mountains and hopefully make new discoveries there.

Many of the mountain areas of Britain are stunningly beautiful, and I would be thrilled if people who love mountains were also encouraged to read the book and discover more about these wonderful wild areas and about the colourful plants that grow beneath their feet as they hike the fells or ‘bag their Munros’. I’ve tried to select photos for the book that are as attractive and compelling as possible to inspire readers to explore and investigate – or just to act as a wonderful souvenir of holidays in Snowdonia, the Lake District, the Scottish Highlands or wherever.

I best sum up my objective for the book at the end of chapter one: “If I can persuade a few… hillwalkers to slow their relentless pace, to look around them as they climb, to venture off the beaten path and explore an interesting-looking crag or delve into the watery runnels that seep from the tops – in other words, to enjoy seeing a hill, rather than just conquering it – then this book will have been truly worthwhile.”

How did you first become interested in botany?

I grew up near Edinburgh Zoo and from an early age spent all my spare time in the zoo getting to know the animals. By the age of 8, I’d decided I wanted to be a zoologist when I grew up – which I thought meant going around the world looking at zoos! That enthusiasm never waned, and I went to Aberdeen University to study zoology. In first year we also had to study botany, and I found that new and fascinating. I knew that plants lay at the foot of all food chains, and therefore that plants were key to how the natural world worked, so I switched over to doing my degree in botany. I was lucky that the university had a field station at Bettyhill on the north coast of Scotland, and some of the first plants I got to know there were montane species growing at unusually low altitudes in the relative sub-arctic climate of the far north. Then, in Honours year, we had an amazing field trip to Obergurgl in the Alps, and I have been hooked on mountain flowers ever since.

You are now lucky enough to spend a lot of your time as a quest speaker on cruise ships around the world; how might you go about getting passengers interested in Britain’s mountain flowers?

It’s funny that you should ask that, because I’m just about to go off on a cruise to Nova Scotia in Canada, and on one of the four days when we sail back across the Atlantic to Liverpool I’m planning a talk called The Lure of Mountain Flowers. I think I’m going to start that with the story of a birdwatcher called Charles Tebbutt, who is best known for his book on the birds of (distinctly unmountainous!) Huntingdonshire. In July 1951, he was walking on a rugged hillside in Inverness-shire, when he spotted a plant at his feet that he didn’t recognise. He collected a few samples of the flowers and leaves, which he sent to various botanic gardens and he was promptly told, with some excitement, that he had discovered a rather handsome flower called Diapensia* which had never previously been recorded in Britain.

That may be 60 years ago now, but I think it shows that there might still be exciting discoveries to be made in the British mountains – and that you don’t need to be a professional botanist to make them! I’ll then go on to a series of beautiful scenic photographs, just to remind folk how beautiful our mountains are, then I’ll show some of our most attractive mountain plants to prove just how much they add to the allure of the hills. That will lead into the mystery stories behind these plants: I’ll speculate why Diapensia is still only known from that single, rather unremarkable hillside and what that might have to do with Norwegian commandos. I’ll tell the story of two attractive little plants that cling to survival in Snowdonia, and why a relative of the garden pinks is known from only two very different sites, one a crag in Lake District and the other a hillside of shattered rocks in Angus. There are plenty of ‘ripping yarns’ from mountain botany to interest cruise ship passengers – and I hope they will also inspire readers of my book.

(* Incidentally, I apologise to any keen botanists reading this who, like me, know many plants better by their scientific names. As in the book, I’m not quoting scientific names here because I don’t want to scare off readers who aren’t botanists – and those of us who are botanists probably have plenty of books in which we can check the scientific names if we need them).

What distinguishes a mountain flower and how many such species occur in Britain?

That’s a really good question. Many of them are species which also grow in the Alpine regions of central Europe or in the Arctic regions of the far north, so they are categorised broadly as ‘arctic-alpines’ – a term that will be familiar to most gardeners. But Britain lies in a special position off the west coast of Europe and its climate is tempered by winds that come off the Atlantic. As a result, many alpine species grow here at dramatically lower altitudes than where they occur in the Alps, and some arctic species also grow here, far south of their normal latitudes. Several species meet on the mountain cliffs of the Lake District or the southern Highlands of Scotland that grow together nowhere else in the world (which makes these especially important conservation sites in an international perspective). I also list in the book several species that grow in Britain at their northernmost or their southernmost sites in the world.

So, although I could define a mountain plant as one that grows typically above, say, 1,500 feet, that doesn’t always work in Britain because many of these come down almost to sea-level on the wind-battered north coast of Scotland or on the Western and Northern Isles – and that’s what makes British mountain botanising so intriguing. In fact, I almost reverse the argument in the book. I have selected 152 species that I regard as typically montane, then, for the purposes of the book, I define mountains as places where these plants grow – and these range from unexpected places like The Lizard in Cornwall, right up to the island of Unst in Shetland.

Tell us more about the unique conditions in the UK and their effect on mountain flower distribution.

The important thing to recognise is that many of our montane species have been clinging to survival on remote mountain ledges since just after the end of the last Ice Age. They survive there because of the chance juxtaposition of the right kind of rock and soil and a local microclimate that mimics the conditions to which they are adapted elsewhere in the high mountains of Europe or the high Arctic. It is vitally important that we try to understand why they survive there and continue to monitor their populations, because these are the plants that will give us the first warning of changes that are likely to happen on a much bigger scale in the Alps and the Arctic because of climate change. They are vital “miners’ canaries” for what lies ahead – plus I think Britain would be infinitely the poorer were we to lose them from our hills.

How have 21st century developments in botanical research affected our understanding of mountain flower ecology?

Hmm… In the strictest sense of botanical research, the latest genetic studies have sometimes made life a bit more difficult, especially for ageing botanists like me! It has changed our understanding of the relationships between species which in turn has led to a lot of changes in scientific names and how species fit into our concepts of plant families. It has also shown that one or two of what we thought were good mountain species are actually just variants of much commoner species, highly adapted to the mountain environment.

What has increased hugely over the 60 years since the last major account of British mountain flowers was published is our knowledge of the distribution of our mountain flowers, thanks to the hard work of hundreds of botanists in recording schemes masterminded by the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland (BSBI). The BSBI published increasingly comprehensive atlases showing the distribution of our native plants in 1962 and in 2002, and recorders are now hard at work gathering data for the next Atlas 2020 project, due to be completed in three years’ time, while, all round the country, enthusiastic botanists have compiled and published detailed accounts of the plants of their local counties or areas. I was given privileged access to the BSBI’s online databases in compiling the information in my book, and I am hugely grateful for that.

What I now want is for readers to prove me wrong! From the BSBI databases, I have tried to note the northernmost and the southernmost sites from where the key montane species have been recorded, and the highest and lowest altitudes at which they have been found, but I am sure keen readers could find new records beyond these extremes – and report them, I hope, to their local botanical recorder. I have reported on sites from which certain species appear to have died out, and I would be thrilled if that encouraged readers to go out and re-find the plants there.

What is the biggest conservation threat to mountain flowers in the UK?

I imagine most informed readers of the NHBS newsletter would expect me to say climate change was the biggest threat to mountain plants, and, in the long term, there is no doubt that climate change is a huge threat. But, as I have tried to show in the book, the impact of climate change on the mountain environment in the short to middle term is difficult to predict with any certainty and may not immediately be as disastrous as we fear.

What is beyond doubt is that, if we are to give montane plants any chance of adapting to the changes ahead, we need to get much better at managing our hills and mountains. Overgrazing by red deer is a huge problem across most of Scotland. The regular burning of moorland areas that are managed for the sport shooting of red grouse or to produce a ‘spring bite’ for sheep tends to encourage a few resilient species at the expense of many other, more delicate plants. Yet some mountain habitats also benefit from restricted amounts of grazing, and if continuing financial challenges lead to further declines of extensive sheep farming in the uplands that could become a big problem too. The challenge lies in getting the right balance between these conflicting priorities – and I’m afraid the decision by the people of England and Wales to leave the European Union (the EU has been a huge help in establishing conservation priorities in Britain) is not going to make that any easier.

Tell us about some specific species you find particularly interesting and that feature in the book.

In the book I have selected 18 species, most of which are rarities, whose distribution and survival particularly intrigues me. I call them “Three-star Mountain Enigmas” for reasons I explain in the book and I give an extended account of each of them. For some of these species, I hope to shed insight, based on the scientific researches of dedicated mountain botanists; for others, I can only pose questions, in the hope of inspiring someone to find an answer. And there are plenty of puzzles in our mountains. Why, for example, is Alpine Rockcress found only in a single corrie in Scotland, when it grows almost as a weed in disturbed ground in the Alps and Arctic? Why (and how) is Iceland Purslane dispersed all the way from Iceland to Tierra del Fuego, yet in Britain it only grows on gravelly slopes on the Isles of Skye and Mull?

In the book, I suggest that Alpine Sowthistle is restricted to tiny populations on just four remote cliffs in the eastern Highlands of Scotland because humans have almost completely destroyed the mountain woods in which it once grew (and where it still flourishes in the Alps and Scandinavia), and I show how the 2001 outbreak of Foot-and-mouth Disease revealed how Marsh Saxifrage and Alpine Foxtail grass are actually much commoner than we ever realised.

For someone interested in a bit of amateur research, where are some of the best spots for finding mountain flowers?

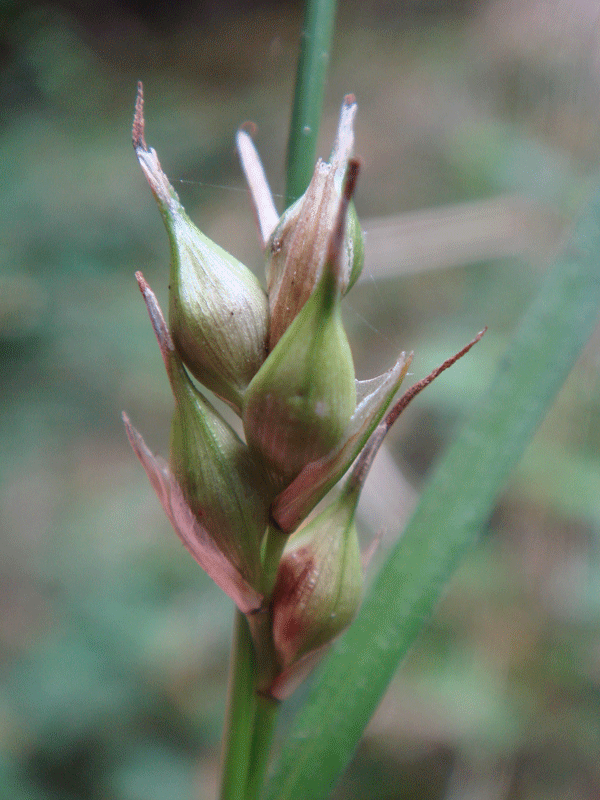

I’d always say that the best place to start is the montane site that is nearest to home, whether that’s the Brecon Beacons, the Peak District, the Pentland Hills or wherever – they’re all covered in the book. Then you can make regular visits through the spring and summer to find each of the local species in full flower and follow them through the season to catch them in seed too (there are some species which you can only identify with certainty if you can find their fruits as well as their flowers) – although I should add that, by the time you read this, it is probably a bit late in the year already for mountain plants, so buy the book and start planning for next year!

Once you have got to know the commoner montane species for your local patch, you can perhaps plan a holiday further afield to one of the real mountain hotspots, like Snowdonia or Upper Teesdale, the Breadalbane hills of Perthshire or the Cairngorm Mountains of Inverness-shire. One spot that I particularly recommend in the book is the area around the Glenshee Ski Area, south of Braemar in Aberdeenshire. The A93 road from Blairgowrie to Braemar rises here to 670m (around 2,200 feet), so montane species grow right beside the car park, but the area is already so well-used by skiers that you needn’t worry too much about damaging the vegetation – and there are some really special plants for plant explorers to find.

It is currently the school summer holiday period – any tips for getting kids interested in botany?

Another great question. Kids like action, and it’s the perfect time of year to show plants in action. Find the different kinds of fruits that plants produce and see how they are dispersed. Find the winged fruits (called samaras) of a sycamore tree or the ‘keys’ of an ash tree and work out how they spread. Who can get their fruit to travel furthest? Find some dandelion ‘clocks’. Don’t just see how may blows it takes to remove all the seeds from the ‘clock’; instead try to follow one of the seeds on its little parachute and find out how far it travels. If you can find a patch of Rosebay Willowherb, investigate how it spreads its seeds. If a riverside near you has been invaded by Himalayan Balsam (aka Policeman’s Helmet); see if you can work out how its explosive fruits have made it a successful ‘Alien Invader’ (in this case from India, not from Outer Space). How do the wild relatives of garden peas and strawberries spread – and what about potatoes? If you want to get really yucky, you might want to ask kids why they think tomato plants sometimes start growing beside sewage treatment plants!

If you have a boggy area nearby, see if you can find Common Butterwort growing there and investigate how its sticky leaves trap little insects which the plant then dissolves and absorbs to get the nutrients it needs to grow. Even better, see if you can find Common Sundew whose leaves are covered in red hairs which curve over to trap little insects caught by the sticky surface of the leaves. Then go online to discover how Venus Flytraps, Pitcher Plants and other insectivorous plants trap their prey – there are some great websites aimed at youngsters about these plants.

Tell us a little about your organisation and how you got started.

Tell us a little about your organisation and how you got started.

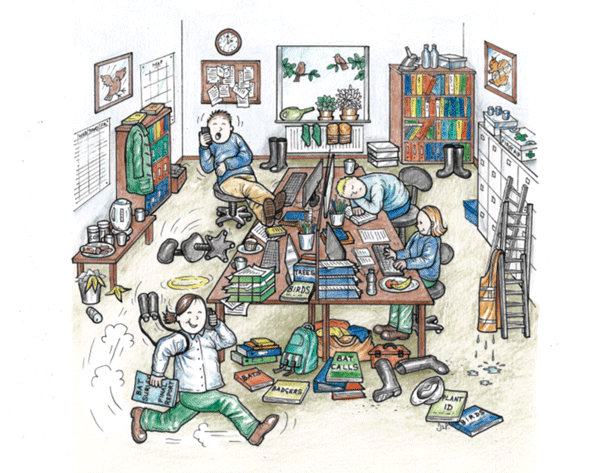

Neil Middleton is an entrepreneurial ecologist who is the managing director of consultancy Echoes Ecology Ltd, and Time For Bespoke Solutions Ltd, a company that provides management consultancy and people development solutions.

Neil Middleton is an entrepreneurial ecologist who is the managing director of consultancy Echoes Ecology Ltd, and Time For Bespoke Solutions Ltd, a company that provides management consultancy and people development solutions.

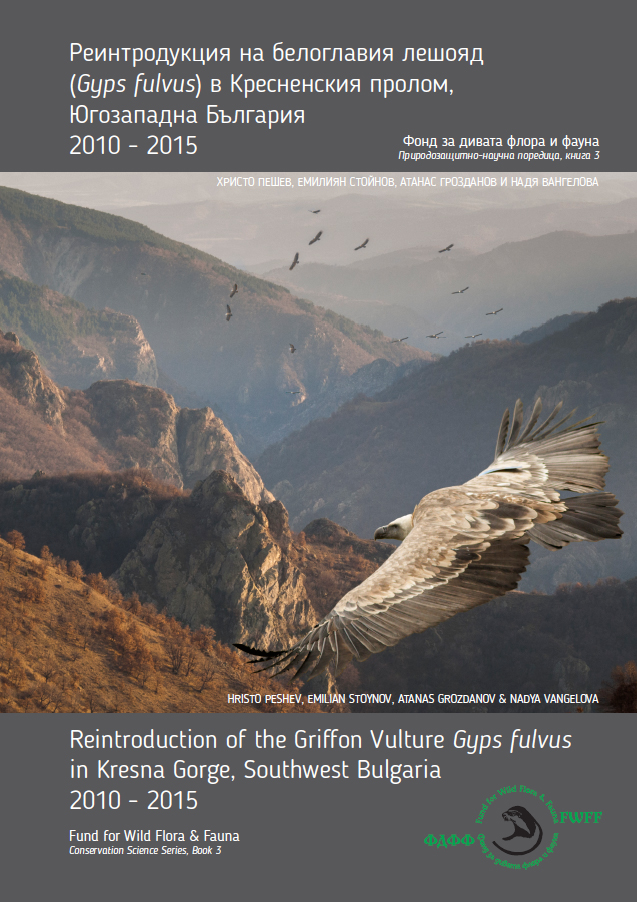

Emilian Stoynov and colleagues created the

Emilian Stoynov and colleagues created the

![Reintroduction of Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus in Kresna Gorge, Southwest Bulgaria 2010-2015 [English / Bulgarian] Reintroduction of Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus in Kresna Gorge, Southwest Bulgaria 2010-2015 [English / Bulgarian]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/vultures-internal.png)