Quick links:

Introduction

Key features

Entry-level choices

Best sellers

Accessories and suggested reading

More information

Introduction

Insect nets are one of the most iconic tools of the entomologist’s kit bag. Around since at least the 1840s, the earliest forms would not have been dissimilar in design or use to those still widely used today. They are, most basically, a deep net bag made of material that is robust but gentle enough not to damage the captured insect, designed to be swept across grass or other vegetation or to catch flying insects as they are spotted. That said, in the last 180 or so years a number of different designs have arisen, making it hard for the aspiring entomologist to choose where to begin.

Sweep nets and butterfly nets – what’s the difference?

As the name may imply, the main difference between a sweep net and a butterfly net is the group that they are designed to catch, and by extension the way in which they are used. Sweep nets are designed to sample a wide range of insects, from flies to beetles, and are usually swept across the tops of vegetation such as long grass before inspection. Because they often come into contact with woody plants and the like, the frame is reinforced and the net material must be reasonably robust to prevent tearing. This has the drawback of making it a little heavy and coarse, and thereby potentially damaging to the wings of very delicate insects like butterflies.

Butterfly nets, on the other hand, have bags that are made from a much lighter, finer material that is less likely to damage delicate invertebrates. This makes them suitable for a few groups, including craneflies, but most notably Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). Of course, the finer mesh is more delicate and likely to be torn by vegetation or powerful insects such as crickets and large beetles.

For the purpose of this buyer’s guide, the term ‘insect net’ will be used when referring to principles that are true of both butterfly and sweep nets.

Key features

Many entomologists relish the challenge of finding a remote, hitherto unexplored site, far away from the beaten path, with undisturbed habitats where anything might be hiding. The equipment we carry, however, can quickly mount up – an insect net, spare bags, pooter, beating tray, collecting tubes, notebooks, camera, not to mention lunch – and can weigh a lot. Many entomologists, therefore, begin with lightweight, compact gear that can be easily transported.

In our opinion, the qualities that determine a desirable insect net are weight and balance, as these will determine how comfortable the user is during long sampling sessions, and the aperture of the frame, as a larger opening means more air passes through, allowing larger sample sizes. But there is always a trade-off. Lighter frames are easier to carry but are less robust. Telescoping handles are portable but are generally made of metal and therefore heavier than a wooden alternative. Larger apertures, though better for sample size, are much more unwieldy than smaller counterparts. The trick to finding a net that really works for you is finding a balance between all these factors.

Frame shape

The ‘head’ of an insect net can be designed in a few different ways; different shapes can maximise the area sampled, and foldable and crushable designs can improve portability. Most entry level nets have a frame that is a simple loop of metal – this keeps them lightweight and cost effective, but limits the size that they can practically be.

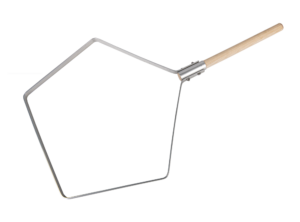

Beyond entry level, sweep and insect nets tend to adopt more complex designs, but they are generally split into three categories: fixed, folding, and crushable frames. Fixed frames are built using the same principle as simpler nets, but often have a pentagonal shape. This increases the overall aperture size without making the net much bigger, allowing for larger samples. Folding frames are usually roughly triangular, and can be folded to make transport easy.

Finally, some butterfly nets are made with a crushable frame. The loop is made of a thin strip of metal that can be twisted around on itself, allowing the net to be stored in a small stuff bag. These are extremely portable, but over the course of use tend to become a bit warped. Crushable frames are generally only used for butterfly nets, as the metal is too lightweight to be robust enough for sweeping across vegetation.

Handle design

When it comes to nets, there are a few considerations to bear in mind. Early insect nets, for example, tended to have quite long handles. But is this necessary? Sweep netting in particular is often carried out at waist height, within easy reach as you walk through a meadow. Not only is it unnecessary in many cases, it is often counterproductive. The longer the handle, the less control you have over the path the end takes, after all. You can extend your arm to reach an insect that is further away, but it is much harder to accurately catch an insect that is too close for your net. A longer handle will also cause wrist strain more quickly, as the weight of the bag and frame cause the net to become poorly balanced. Most basic nets – particularly sweep nets – are therefore given a short handle to stay light, well balanced and portable.

That said, a longer handle can still be of use. You may want to sample from trees above head-height, for example, or target a group that is very visual and likely to flee before you get close enough for a short-handled net. One such group is Lepidoptera, and for this reason some butterfly enthusiasts prefer butterfly nets with a longer handle. You’ll see long-handled nets used for catching flying invertebrates referred to as ‘aerial nets’ in some literature.

A good option for either net type is a telescopic handle. This allows the user to decide what length is best for them, and affords some flexibility for activities, such as sweeping around trees. They tend to be heavier and less well balanced than non-telescopic alternatives though, and can be prone to breaking over longer periods of heavy use.

Entry-level choices:

Bestsellers:

- Professional Sweep Nets

- Telescopic Folding Sweep Net

- Standard Sweep Net

- Professional Butterfly Net

- Folding Butterfly Net Set

Accessories and suggested reading:

- Invicta Pooter

- Glass Specimen Tubes

- Studying Invertebrates

- Handbook for Lepidopterists

- Britain’s Insects

- ID Guide to Garden Insects of Great Britain & North-West Europe

More information:

The NHBS Guide to UK Butterfly Identification

The NHBS Guide to UK Bumblebee Identification

The NHBS Guide to UK Hoverflies: Part 1

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.

natural world and to human society. With an expert eye, Goulson skillfully guides the reader through different aspects of their importance, from the multi-million pound service that dung beetles provide the farming industry each year in the UK alone to the vital role that pollinators play in underpinning ecosystems across the planet, and the value that insects have in their own right as beautiful, vibrant denizens of our planet. The author’s passion is infectious; it is difficult to read this section without becoming invested in the wondrous ranks of the planet’s invertebrates, making the threat of their decline feel all the more personal.  controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.

controversial among some parties. He consistently highlights the arguments of his critics, treating them with respect and validation. At some points he provides his rebuttal while at others he admits to the shortcomings of the relevant research, explaining why a different approach was impossible at the time. This is indicative of an attitude that permeates the book – the issues that he writes about are bigger than minor gripes with experimental methodologies, bigger than business margins or political leanings. He presents with a neutral eye the irrefutable reality that insects are vanishing at a terrifying rate, and unless action is taken the world is heading towards a very real disaster within generations. Though frequently distressing and at times heartbreaking, Goulson writes with a voice compelling and just witty enough to prevent the reader from becoming despondent. This book is not intended to drive us to despair, but to action.  encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.

encouraging native plants in our towns and cities and overhauling the way in which we view farming. Finally, there is an extensive list of actions, large and small, that people can take, listed by occupation. This section is what the book has been building to, and it is worth reading for this alone. As usual, respect is paid to all viewpoints and all members of society. It doesn’t matter whether the reader is in a position where a free-range organic, locally sourced diet is financially viable or not – there will be other actions that they can take regardless of financial matters. Nor does it matter if they have beliefs, political or economic, that might conflict with the author’s. It is a call for society to overlook such matters which are, in the face of such a crisis, trivial.

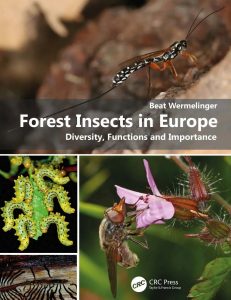

Much of the information comes from my readings or lectures. However, since I wanted to portray the ecological and economic importance of forest insects as broadly as possible, I still had to review a lot of published material. Above all, I wanted to support quantitative data with accurate citations. Owing to the Internet, such research is easier today than it was 20 years ago… Fortunately, I also had my own photographs on almost all topics.

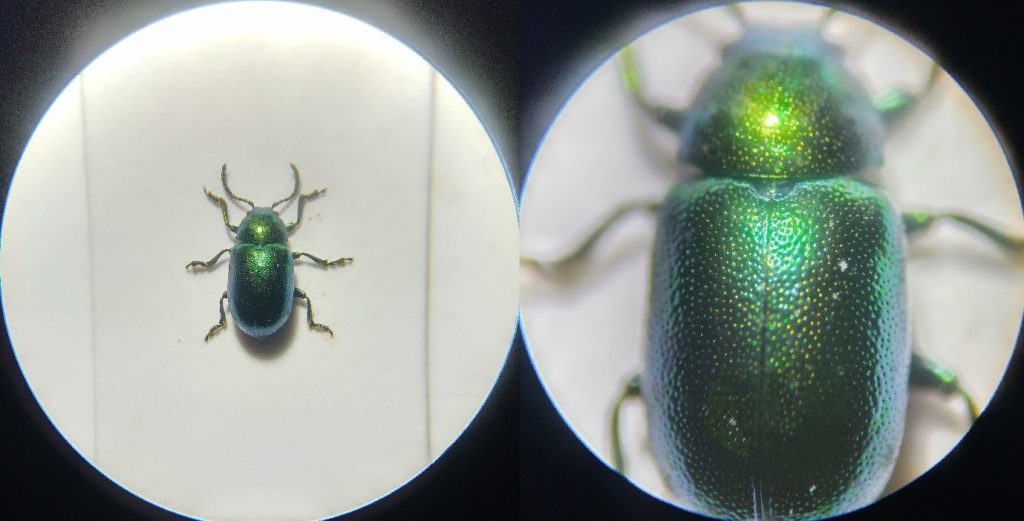

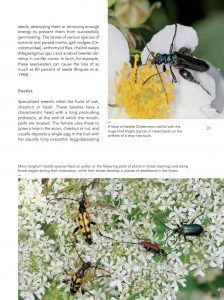

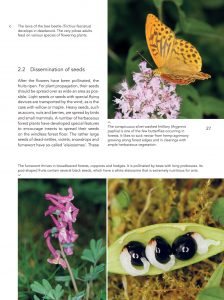

Much of the information comes from my readings or lectures. However, since I wanted to portray the ecological and economic importance of forest insects as broadly as possible, I still had to review a lot of published material. Above all, I wanted to support quantitative data with accurate citations. Owing to the Internet, such research is easier today than it was 20 years ago… Fortunately, I also had my own photographs on almost all topics. Professionally, I am mainly concerned with wood-dwelling insects. I am especially interested in the bark beetles, and their natural enemies as well as the intensive interactions with their host trees. Bark beetles are known to be pests, but they are also pioneers in the decay of wood. I also deal with the wood-dwelling longhorn beetles and jewel beetles, which often lend themselves to photography because of their size and beauty. For decades I have dealt with the development of their biodiversity after disruptive events such as storms or fire. The social red wood ants or the galling insects also fascinate me with their ingenious way of life.

Professionally, I am mainly concerned with wood-dwelling insects. I am especially interested in the bark beetles, and their natural enemies as well as the intensive interactions with their host trees. Bark beetles are known to be pests, but they are also pioneers in the decay of wood. I also deal with the wood-dwelling longhorn beetles and jewel beetles, which often lend themselves to photography because of their size and beauty. For decades I have dealt with the development of their biodiversity after disruptive events such as storms or fire. The social red wood ants or the galling insects also fascinate me with their ingenious way of life. There are two main causes for the decline in much of the forest insect fauna. The intensive use of wood in the past centuries has led to the fact that the forest area in Europe has decreased significantly over a long period of time, the trees no longer reach their natural age phase, and there were almost no dead trees that could slowly rot. In the case of many wood-dwelling insects that are dependent on so-called habitat trees or develop in decayed, thick tree trunks, this has led to a severe threat to their biodiversity. In recent decades, the forest area has increased again and in many countries the preservation of old trees and dead wood is being promoted. However, the impact is still modest.

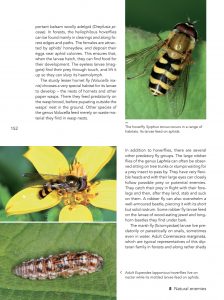

There are two main causes for the decline in much of the forest insect fauna. The intensive use of wood in the past centuries has led to the fact that the forest area in Europe has decreased significantly over a long period of time, the trees no longer reach their natural age phase, and there were almost no dead trees that could slowly rot. In the case of many wood-dwelling insects that are dependent on so-called habitat trees or develop in decayed, thick tree trunks, this has led to a severe threat to their biodiversity. In recent decades, the forest area has increased again and in many countries the preservation of old trees and dead wood is being promoted. However, the impact is still modest. The main problem when photographing small objects is always to be able to focus as much as possible on them. This requires a small aperture and therefore a lot of light. I photograph everything “hand-held” and therefore the shutter speed should be short. For these reasons, I almost always use a ring flash with separately controllable halves and 100 mm macro lens with my SLR camera. Nonetheless, even cameras with a small sensor (even mobile phones!) can nowadays produce surprisingly good images of larger, less volatile insects.

The main problem when photographing small objects is always to be able to focus as much as possible on them. This requires a small aperture and therefore a lot of light. I photograph everything “hand-held” and therefore the shutter speed should be short. For these reasons, I almost always use a ring flash with separately controllable halves and 100 mm macro lens with my SLR camera. Nonetheless, even cameras with a small sensor (even mobile phones!) can nowadays produce surprisingly good images of larger, less volatile insects.