Richard Mabey is often referred to as the father of modern nature writing. His latest book is a retrospective of occasional writings compiled by the author over the last couple of decades. In the author’s words; ‘a sketchy reflection of a life’s work does emerge‘ He has taken time to sign copies of his latest book and answer our questions about fifty years of nature writing.

Richard Mabey is often referred to as the father of modern nature writing. His latest book is a retrospective of occasional writings compiled by the author over the last couple of decades. In the author’s words; ‘a sketchy reflection of a life’s work does emerge‘ He has taken time to sign copies of his latest book and answer our questions about fifty years of nature writing.

1. Could you tell us a little about your background and how you got interested in nature?

I was one of that generation of kids allowed to run wild out of doors. We had a hundred-acre abandoned landscape park at the end of the garden, and in it, I saw my first barn owls, smelt my first storm-splintered wood and ate my first hawthorn leaves. Later I was a boy-birder, and by my teenage years began attaching huge symbolic importance to them. The first chiffchaff had to sing in a particular ash clump, the first swifts had to appear on May Day, and I held my blazer collar for luck on the walk to school to will them back. I did my first nature scribblings then, essays and over-romantic poems, shamelessly aping Richard Jefferies and Dylan Thomas.

I went to Oxford to read biochemistry despite never having done a mite of formal biology- but recoiled in horror from the curriculum and changed to philosophy and politics in my first fortnight. I’ve never regretted the change, for the perspective it gave me, or for the fact that school made me just about scientifically literate.

2. Your new book looks back over a life’s work and features a collection of ‘occasional writing’; how did you decide which works to include?

I realised I had got a good portion of the work already done. Over the past 20 years, I’ve done a fair amount of writing – essays, introductions to other writers’ books, radio programmes – which contain autobiographical elements. So, a long think piece I wrote for the Guardian about the history of foraging in Europe contains an account of how I came to write my own contribution, my first book, Food for Free. A BBC Radio 3 talk I delivered live from Bristol (as part of a Nature and Music festival) became an exploration of the relation between birdsong and human music. I worked a lot on most of the pieces, extending them and cutting out overlaps, and strung them together so that they made a rough sketch of a working life.

3. Is there one ‘nature writer’ that has been an inspiration to you?

There are dozens. But the one who struck most sparks is Annie Dillard. Her Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974) uncoiled new mycorrhizal links between imagination and the physical world. Pilgrim is a poetic interrogation of evolution, done through an acute contemplation of the natural life of a remote Appalachian creek. Why should anything – light, love, leaf – be the way it is? Dillard’s style is mischievous, gleeful, explosive- just like creation itself. I’ve long been a fan of American nature writing- Barry Lopez, Gretel Ehrlich, Gary Snyder, back to the master Henry Thoreau. The States’ vast untrammelled landscapes seem to nourish a similar freedom in its writers, in contrast to our own corseted acres. The British writers who have most inspired me tend to be radicals who set themselves against this ordered and orderly back cloth; eg John Clare and his poems of solidarity with commoners of all species; Kenneth Allsop, firing broadsides through conventional “country writing” in the 1970s.

4. Do you think the genre of nature writing has changed during the time you have been writing?

I’ve been writing for more than fifty years, so have the luxury of a long view. But I think the idea that the nature writing of the last ten years is in some essential way “new” suggests a great forgetting of our tradition. Current nature writing is a very broad church, from lyrical science to introspective memoir. Yet even the most conspicuous trait – the personal “journey” – has deep roots. I’m no fan of his work but think of Gavin Maxwell in the 60s or John Buxton in the 40s and WH Hudson at the beginning of the 20th century. One of the most exciting trends is the emergence of fiction with strong affinities to the agendas of nature writing, as in Richard Powers’ astounding epic The Overstory (but this too was happening in pre-WW2 fiction).

5. You have won awards and many accolades for your writing; what is your proudest achievement as a nature writer?

I think it would have to be Flora Britannica (1986) not least because it incorporates the voices and stories of many thousands of contributors as well as my own. When I set out my plan to try and survey where wild plants stood in our culture in the late 20th C, I was met with heavy scepticism at first. “Nowhere” was the implied response. When the contributions began to pour in from the general public they were heart lifting, not just for their passion but their diversity. There was very little of the rehashed Victoriana usually passed off as “folklore”. Instead we had deeply felt personal stories from individuals, families, children’s gangs, about the importance of wild plants in their lives: plants used in weddings, and tossed onto a parent’s coffin; outrageously inventive playground games with invasive aliens; favourite local trees used as landmarks, hideaways, sites for lovers’ trysts.

The four years I spent working on this book were certainly the most rewarding of my writing life. I toured the UK meeting contributors, looking at locations, and then in the long writing process (it is a quarter of a million words long) trying to relate these contemporary experiences to the plants’ social histories and ecologies.

6. The loss of nature seems to be more prominent as a newsworthy subject; do you think nature writing can help towards restoring nature and if so how?

The language of loss is as hard to create as to read. I know I’m far from alone in finding that my head and my heart can pull in opposing directions. My intellectual understanding of the terrible collapse of nightingale populations cannot co-exist with the rapturous in-the-moment experience of listening to its song. But I’m encouraged by what has been happening in the last couple of years when the crises of climate change and extinction seem to have revealed not just the vulnerability of the natural world but a new appreciation of its resilient vitality. To paraphrase Amitav Ghosh is his powerful book The Great Derangement (about the implications of ecological catastrophe on writing) it is as if the improbable events that are happening to us have brought about a recognition that humans have never been alone, but live alongside beings who share with us elements we have always assumed were uniquely ours: sentience, will and above all agency. The challenge writers face is how to express this more-than-human agenda in human words.

7. Have you got any future projects planned that you can tell us about?

Age creeps on, and ideas are scarcer fruits. I have no particular plans but hope I’m not written out. Maybe I’ll do a short philosophical meditation on the concept of human-nature “neighbourliness” which I begin to explore in Turning the Boat for Home. Ideas from readers most welcome!

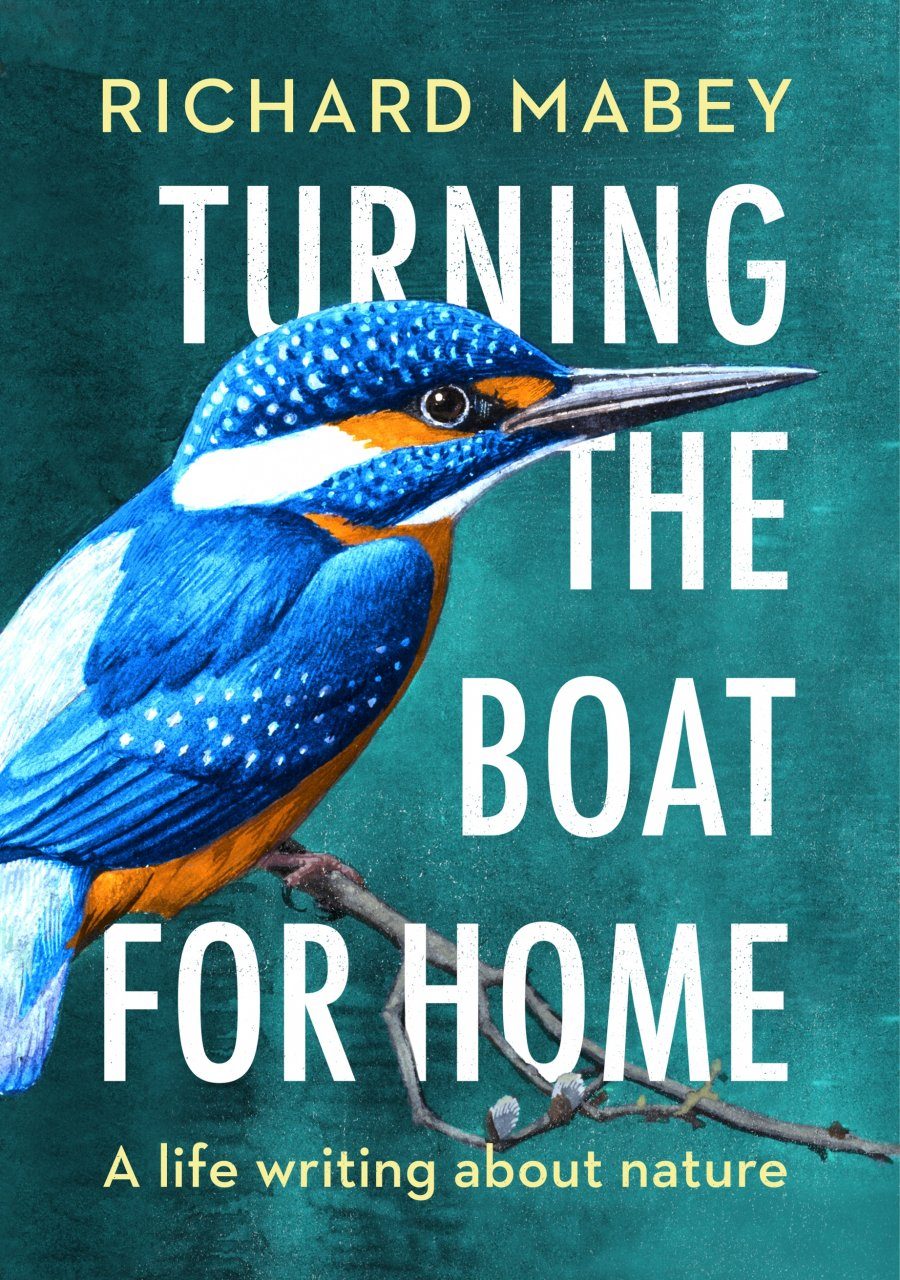

We have a limited amount of signed copies available of Turning the Boat for Home: A Life Writing about Nature

Turning the Boat for Home: A Life Writing about Nature

Turning the Boat for Home: A Life Writing about Nature

Hardback, Oct 2019, £15.99 £18.99

Due to be published in 2020

Birds Britannica

Birds Britannica

Hardback, due March 2020, £42.99 £49.99

Fifteen years after the very successful first edition, Mark Cocker and Richard Mabey return for the second edition of Birds Britannica, paying homage to the strong bond the British have with birds.

Browse all our Richard Mabey’s books.