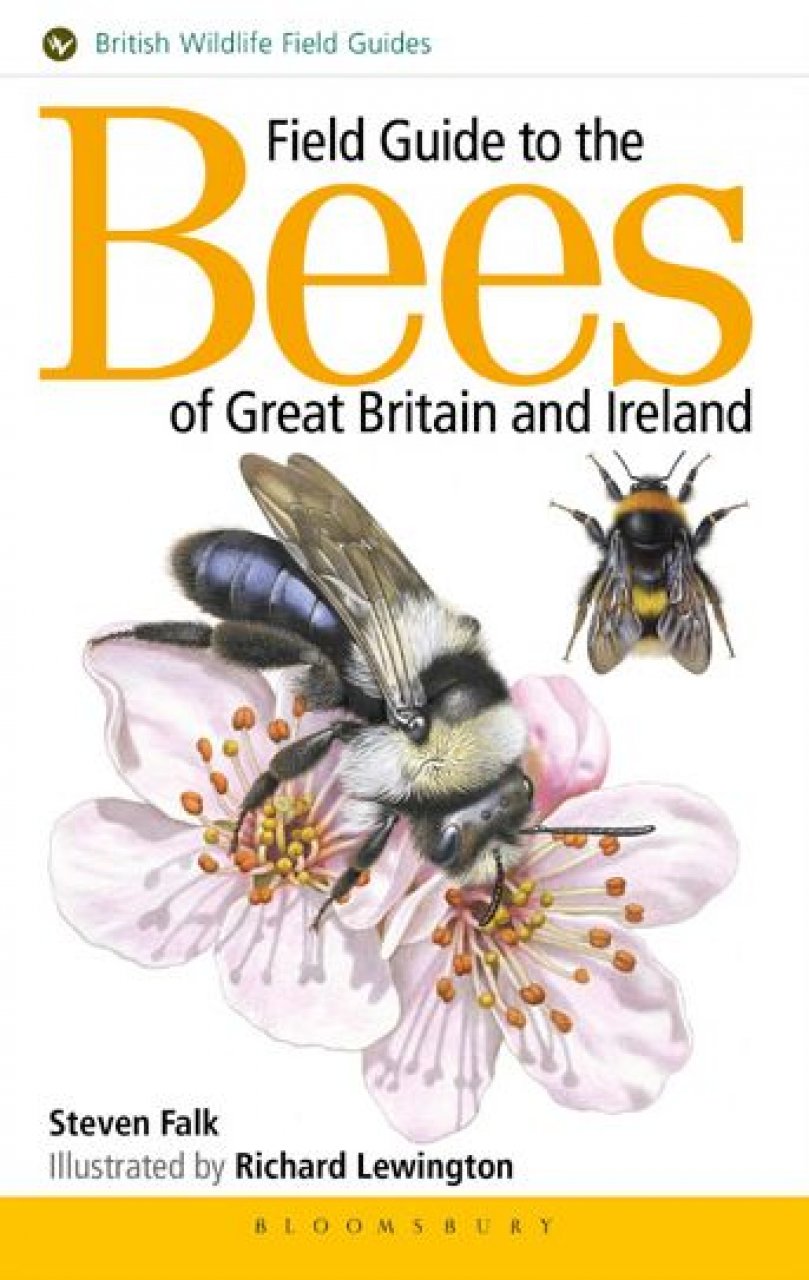

Naturalist and wildlife artist Steven Falk has had a diverse career with wildlife and conservation, including working as an entomologist with Nature Conservancy Council, and as natural history keeper for major museums. He is now Entomologist and Invertebrate Specialist at UK invertebrate conservation organisation Buglife. His new Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland will be published by British Wildlife Publishing next month.

Naturalist and wildlife artist Steven Falk has had a diverse career with wildlife and conservation, including working as an entomologist with Nature Conservancy Council, and as natural history keeper for major museums. He is now Entomologist and Invertebrate Specialist at UK invertebrate conservation organisation Buglife. His new Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland will be published by British Wildlife Publishing next month.

Tell us about your role at Buglife.

At Buglife, I have quite a diverse role. I provide information and advice to colleagues, external enquirers and a plethora of external organisations. I’ve been particularly involved with overseeing the production of new red lists for assorted invertebrate groups, also providing feedback to the various national pollinator strategies, new agri-environment schemes, plus helping to develop projects for some of our most endangered invertebrate species. We also have a consultancy now, Buglife Services, which carries out and coordinates invertebrate surveys all over Britain. We’ve just done an exciting survey of the A30 and A38 in Devon and Cornwall. We need more understanding of road verge invertebrates, especially pollinators.

How did you come to write this landmark identification guide to all the bees of Britain and Ireland?

I was approached by Andrew Branson in 2012 and was initially quite reluctant, because you cannot use a traditional field guide approach for bees, as many cannot be identified to species level in the field (they require the taking of a specimen for critical examination under a microscope) and it is crucial that we keep the national dataset (run by BWARS) clean and reliable by being honest about where the limits of field identification lie. So I agreed to write it on the basis that it covered all 275 species, had reliable keys, and could appeal to both hardcore recorders and general naturalists. I knew this was feasible, because we had faced the same challenge with the seminal book British Hoverflies (Stubbs & Falk, 1983, 2002). So it is a field guide in the loose sense – it will help you to recognise much of what you see in the field, but also indicate at which point you need to take specimens and put them under a microscope. But you don’t need to collect bees or have a microscope to enjoy the book – we made sure of that.

There is growing concern about the conservation status of bees – how are our bees getting on, and how might the publication of this book help them?

There is growing concern about the conservation status of bees – how are our bees getting on, and how might the publication of this book help them?

Yes, we need to be concerned about bees. We have already lost 25 species and several more are teetering on the edge of extinction. Good bee habitat continues to be lost. Brownfield land came to the rescue last century, but most of that has now been developed or lost its flowery early successional stages, which is what so many bees need. The research being carried out on pesticides such as neonicotinioids is also pretty disturbing – check out the work by Prof. Dave Goulson at Sussex University. It seems to be affecting bee numbers in many parts of the country. The national pollinator strategies being published by UK member states are a call to arms – let’s get monitoring bees. But the emphasis is on developing citizen science to achieve some of this, because there is little funding. High quality amateur recording is part of this plan, and Britain’s strong tradition of this makes it a realistic proposition. But the last comprehensive coverage of British bees was Saunders, 1896, and it has been the lack of modern ID literature that has held bee recording back. Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland, and the supporting web feature (embedded in my Flickr site) will hopefully fix this!

Your career as a wildlife artist began early – you worked on the colour plates for Alan Stubb’s guide to British Hoverflies when you were just a teenager. How did this collaboration come about?

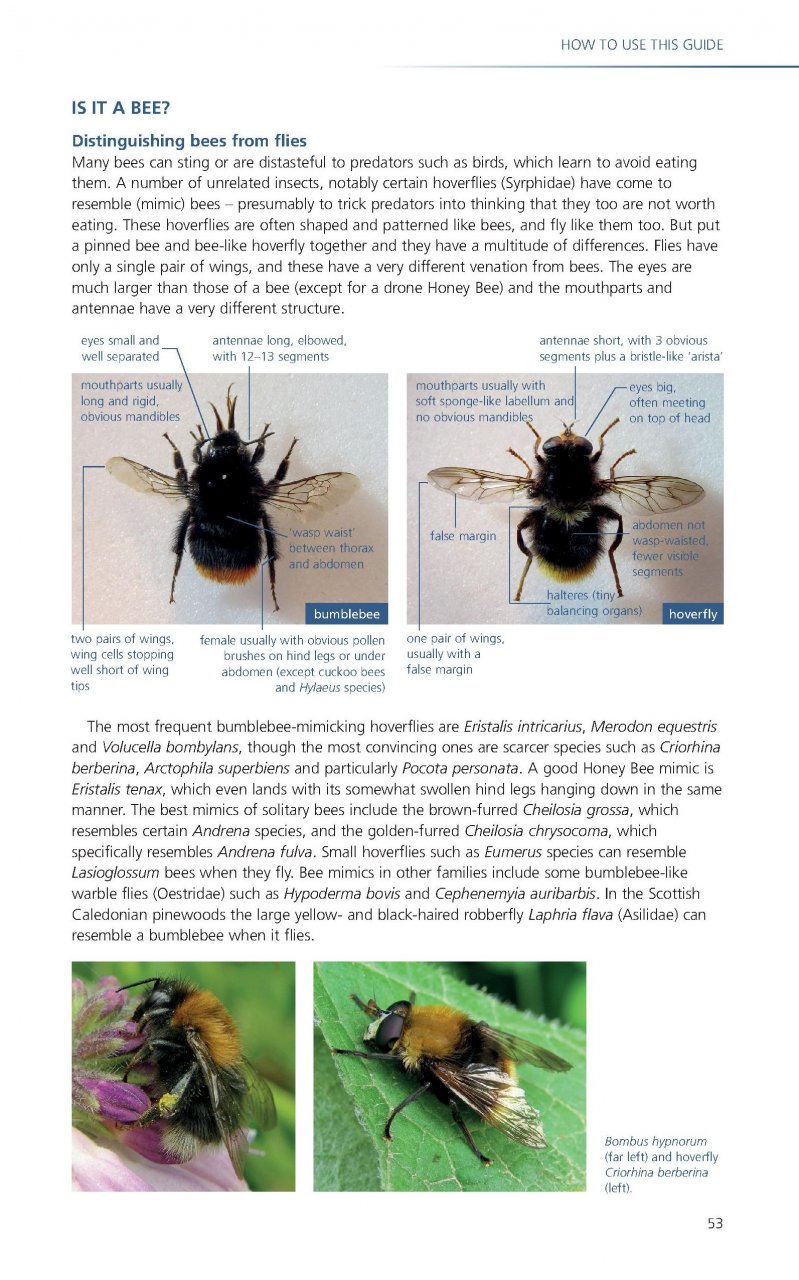

I pinned some bumblebees I had caught near my home in North London when I was 12. Half of them turned out to be bee-like hoverflies, and that started a fascination with hoverflies. The following summer holiday, I went out with a net almost every day, and seemed to find a new type of hoverfly daily. I was totally hooked on them, and I painted things that fascinated me, including those hoverflies. I exhibited some hoverfly artwork at the 1976 AES Exhibition in Hampstead, and met Alan Stubbs who told me he was writing a new guide to hoverflies. I said I wanted to do the artwork (I was only 14), and the rest is history. It took 3 years of evenings, and I think I was 17 when I finished it. I’m very proud of those plates, and you can see how my style develops (plate 8 was the first and plate 7 was the last – you can see a lampshade reflection in the early ones!).

Do we see any of your artwork in this book?

Do we see any of your artwork in this book?

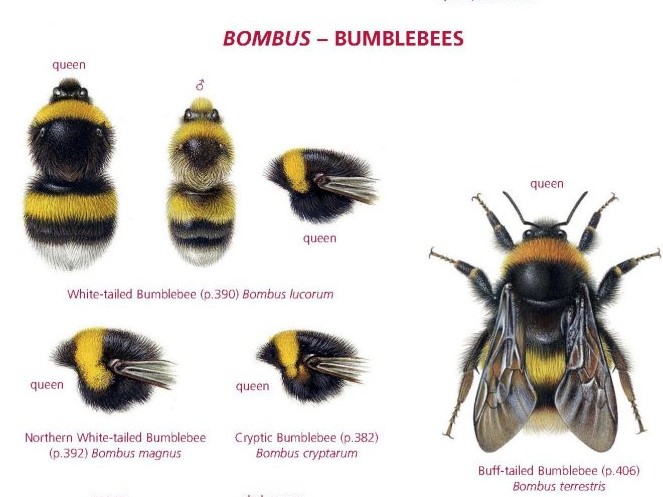

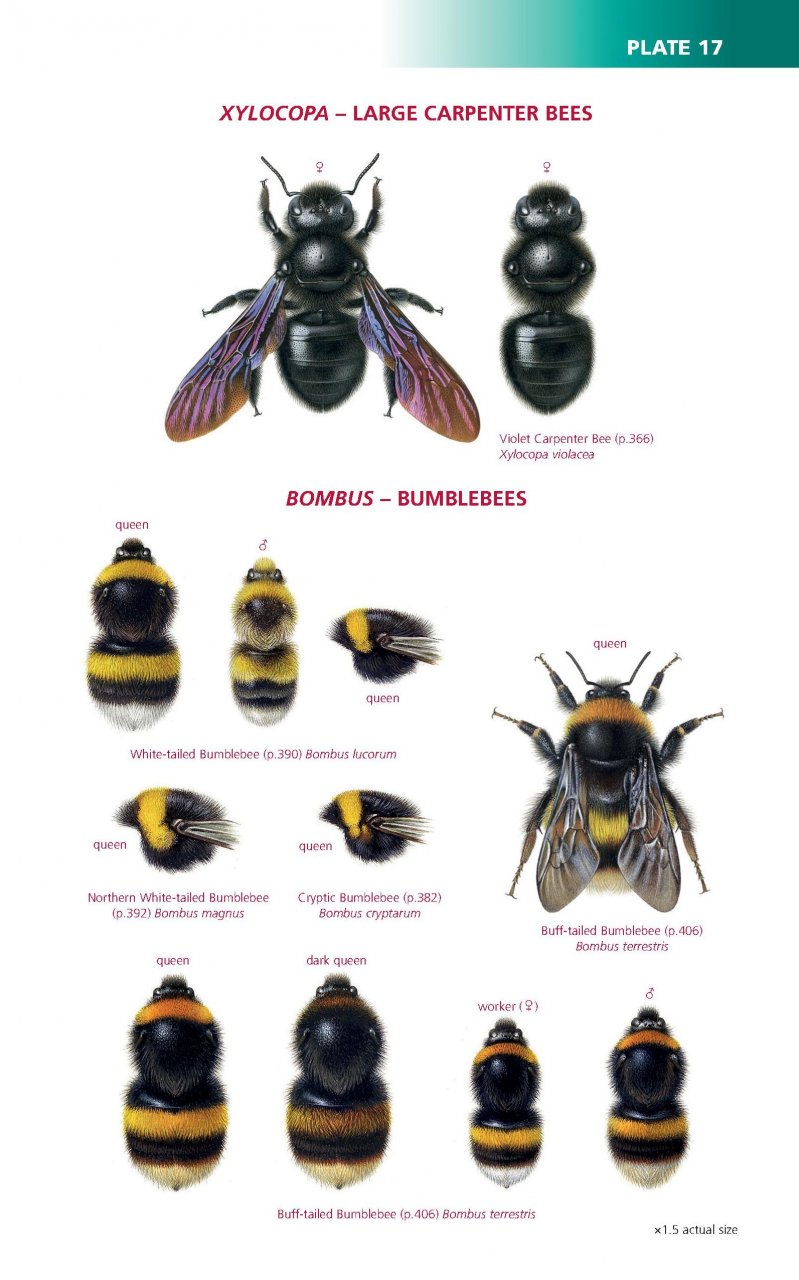

Sadly not, my eyesight is not great these days and I do very little drawing and painting now. But the British Wildlife Publishing ‘house artist’ is the great Richard Lewington, and he’s done a magnificent job. The bumblebee plates in particular, are just stunning, the best ever produced.

What sort of techniques do you use to produce your artwork – which is strikingly realistic and very detailed?

I painted birds a lot as a young child and was very aware of the bird artists of the time and their styles, people like Basil Ede, Charles Tunnicliffe and Robert Gillmor. I particularly liked the detail and photo-realism of Basil Ede’s work and became aware that he used gouache. So I started to use gouache and preferred it to watercolour. I’d often start with a black silhouette and build up the colour and texture on top of this, which is the opposite of watercolour painting. But others, like Denys Ovendon and Richard Lewington, show what can be done with watercolour, so it’s just a taste thing. For really intense or subtle colours, I’d need to use watercolours, because they produce a much larger colour pallete than gouache. Richard knows his watercolours – you need to if you want to tackle butterflies like blues, coppers and purple emperors. I’m possibly more proud of my black and white illustrations than my colour work. Here I was most influenced by the likes A. J. E. Terzi and Arthur Smith, house artists for the Natural History Museum. Their use of cross-hatching and stippling is so skillful, and I’ve tried to emulate this in my pen and ink artwork. Never use parallel lines in cross hatching!

Any future interesting projects coming up that you can tell us about – artistic, or conservation-based?

There are many more books I’d like to write, especially for wasps and assorted fly groups. It’s not just the subject, it’s the approach. I like getting into the mindset of the beginner and finding the right language and approach. We need to get more people recording invertebrates. I like the double-pronged approach of books plus web resources, and I have a popular and ever-expanding Flickr site that greatly facilitates the identification of many invertebrate groups. On the conservation front, I’m keen to continue promoting understanding of pollinators and to increase the effectiveness of agri-environment schemes. Invertebrate conservation is in my blood and I’ll be pursuing it to the very end in one form or another. I might even try illustrating again one day if I can find the right glasses!

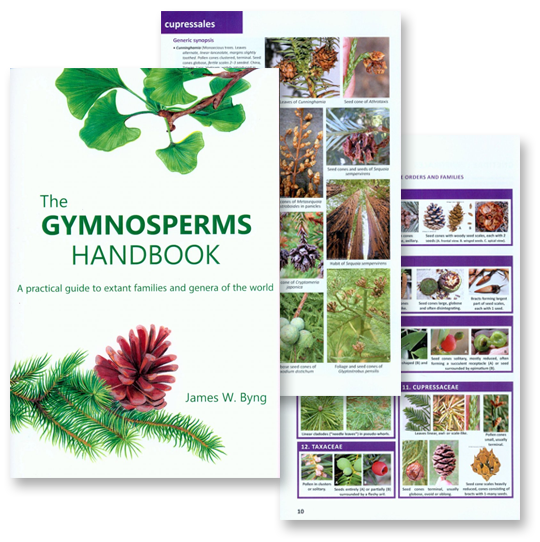

Order your copy of the Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland

Visit Steven Falk’s website