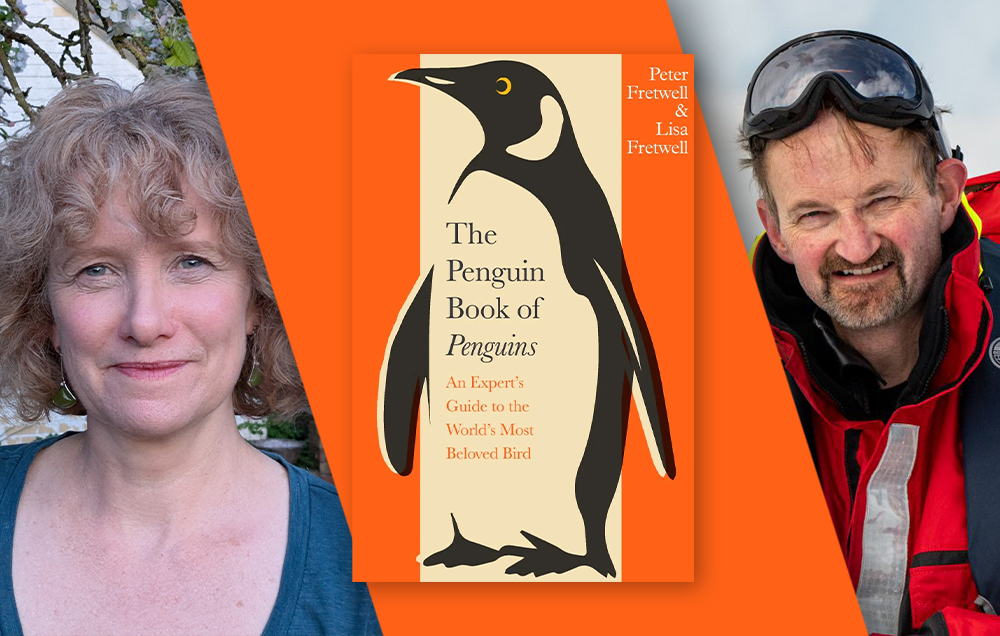

A Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, Dr. Peter Fretwell, like the subjects of his new book entitled The Penguin book of Penguins, spends the majority of his time in the cold. As a senior geographic and remote sensing scientist, Peter has been responsible for leading many projects that further our understanding of the Polar regions and the wildlife that inhabits the area. Establishing and contributing to key projects to help better understand predators in the polar region by using satellite imagery has assisted in crucial conservation efforts.

A Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, Dr. Peter Fretwell, like the subjects of his new book entitled The Penguin book of Penguins, spends the majority of his time in the cold. As a senior geographic and remote sensing scientist, Peter has been responsible for leading many projects that further our understanding of the Polar regions and the wildlife that inhabits the area. Establishing and contributing to key projects to help better understand predators in the polar region by using satellite imagery has assisted in crucial conservation efforts.

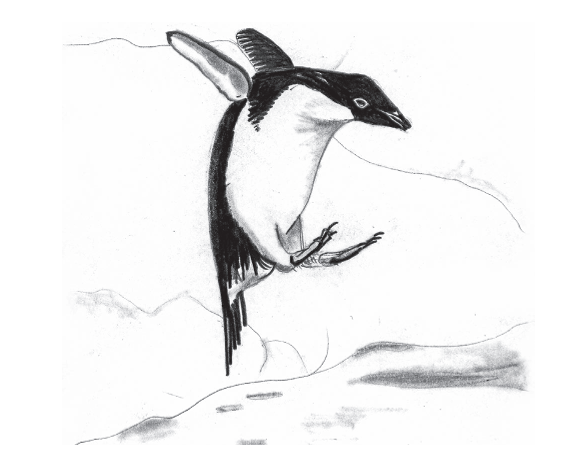

For this book, Peter has joined forces with his wife Lisa who provides a unique selection of illustrations throughout the book. As an artist of over 30 years, Lisa draws on a wealth of experience having exhibited her works in London and New York.

We were lucky enough to catch up with Peter and Lisa recently to talk about the new publication.

What inspired you to write “The Penguin Book of Penguins”? Why penguins?

Peter: Strangely, there has never been a book titled The Penguin Book of Penguins, so when we were asked to write it, it was an opportunity we couldn’t turn down. I had previously written the Antarctic Atlas, published by Penguin Random House in 2020 and I have worked with penguins and on penguin science for twenty years. These small charismatic creatures are such a delight to be involved with, and they are a major part of working in Antarctica. Working at the British Antarctic Survey you pick up stories and anecdotes about them almost by osmosis, so having a chance to relay those narratives to a wider audience is a real privilege. We all love the jovial nature of these unique birds and their amazing adaptations to survive and thrive in some of the most challenging environments on Earth, but there is a more serious message that I also wanted to convey about the challenges that many of the species now face with climate change, pollution, habitat loss and overfishing. Communicating these challenges to a wider audience is one of our main drivers, whilst keeping the message light and not too “preachy”, to engage and inspire that wider readership. What was more, we decided we wanted to include drawings rather than photos, so my wife, Lisa, who is a professional artist joined the author team to bring the illustrations to life.

How has your work as a cartographer and scientist at the British Antarctic Survey influenced your writing and perspective on penguins?

Peter: I really started researching penguins through my work on mapping and remote sensing. I started my scientific career as a geographer and got a job in the British Antarctic Survey as a cartographer. I have always loved maps, especially mapping the natural world around us, but I also loved the science and was soon not just making maps but helping with the geospatial analysis. The British Antarctic Survey is a wonderful and diverse place for environmental science and to help the scientist analyse their data was fascinating – you never knew what you might be working on; one day it could be mapping and analysing volcanoes, and the next it might be cuttlefish distribution. In 2008, whilst making a map for our pilots, I discovered that we could see emperor penguin colonies in freely available Landsat satellite imagery. At the time, we didn’t know how many emperor penguin colonies there were or their distribution, so it was a groundbreaking discovery.

How has the use of satellite imagery revolutionised the study and conservation of penguin colonies?

Peter: Fast-forward 17 years and we now know that there over double the number of colonies that we thought there were. We track their locations each year and do annual population assessments using satellite imagery. We have also used the technology to discover unique, previously unknown behaviours and traits, and we have witnessed and recorded the struggles and calamities they suffer as the continent warms and the sea ice diminishes. The Earth observation methods that we developed for emperors have been transferred to many other species of penguins and other types of wildlife around the world. My job itself has changed dramatically, from a scientific cartographer to a remote sensing expert and an expert on penguins and other polar vertebrate species that we track from space.

What were the major obstacles or challenges you’ve come across during your study of penguins?

Peter: Using satellites is a brilliant way to study these animals as most of the colonies are in extremely remote locations, where on-the-ground research is almost impossible. Even now the resolution of the most powerful satellites is still not good enough to see every individual adult and chick. We still need to get out there to calibrate our satellite counts and see how accurate they really are, but getting to emperor penguin colonies and synchronising ground (usually a unmanned aerial vehicle or UAV) counts with satellite data is really challenging, not just for emperor penguins, but for all the wildlife that we study from space. One of our current technical challenges is to improve the methods.

Lisa: Finding the inspiration and imagery for the more temperate penguins was quite challenging. The Antarctic and sub-Antarctic penguins were easier, as Peter had taken hundreds of photos of all the species throughout his career that I could work from. We had also visited New Zealand and seen many of the penguin species, like the adorable little blue penguin, there. On his travels, Peter had also photographed penguins on the Falklands and South America, but there were still some species that we had to trawl through published sources to get good reference images for. You have to be careful as what you see on the internet is not always correct, but it helps when you are married to a penguin expert!

Many people feel rather enamoured by penguins. Why do you think that is?

Peter: I agree, and it’s hard to put your finger on the reason. Maybe it is a combination of their comic trusting nature and the fact that they are one of the few animals that stand upright on two legs, which makes them look a bit like us. It is really hard not to anthropomorphize penguins and compare them to little people with similar habits and social structures. Like us they often live in huge congregations, sometimes hundreds of thousands strong, they have complex courtship routines, bicker with their neighbours and do daily commutes to look after the family. They are also very tame, curious and often clumsy, which makes them quite endearing. Add their incredible, unique abilities in response to their challenging environments and you have an animal that really is quite engaging.

What are the biggest misconceptions about penguins that you would like to clarify?

Peter: There are many. Firstly, and perhaps obviously, penguins are a bird. They have feathers, not fur. Secondly, not all penguins live in Antarctica. A minority, only four of the eighteen species, breed around the coasts of the Southern Continent, but it’s fair to say that almost all (except for a few hundred) live in the Southern Hemisphere and most of them would call the waters around the Southern Ocean home.

What are the primary threats to penguin habitats, and how can these be mitigated?

Peter: It’s not just their habitats, but we can start there. Over the years, penguins have been eaten, killed for their feathers, had their eggs collected in their millions, been squashed and boiled down for their oil, and had their nesting habitats dug up and destroyed for fertiliser. In more recent times, urbanisation and land clearance has affected some of the more temperate birds, and the introduction of non-native species has had a devastating impact on many of the island-living species that are endemic to just one small group of islands.

Today, the main threats to the temperate species of penguins that live close to humanity are pollution from oil spills, overfishing and bycatch in their foraging grounds. But even in Antarctica and the remote island homes of penguins that no one ever visits, the influence of humans is affecting populations. Climate change is a global, man-made phenomenon that cannot be averted at a regional scale and is starting to have dramatic effect on many species. Although it is fair to say that in a warming environment, there will be winners and losers, at the moment, it looks like we will see more losers than winners.

What conservation efforts have been most effective in protecting penguin populations?

Peter: Around the world there are many amazing people and organisations helping penguins, from re-homing little penguins in New Zealand and Australia to the fantastic efforts to save African penguins from oil spills. In South America, there has been a great effort to protect breeding colonies from predation and on many sub-Antarctic islands there have been great programmes to eradicate non-native species that eat eggs and chicks, and trample breeding sites. There are fantastic efforts in many places that are saving penguins from the brink of extinction that anyone who loves or admires these birds should be grateful for.

Personally, what thoughts and feelings were you left with after this study of penguins?

Peter: Writing the book has not only highlighted how much we love penguins and how our culture has embraced these charismatic birds, but also the paradox of how badly we have treated them over the years and how threatened they are from human activity. Today most of those threats are indirect, but they are still caused by us and can still be solved by us.

Lisa: In terms of illustrations, I had to re-draw the ‘Penguin Digestor’ numerous times, because it made me feel a bit queasy just thinking about it. If you look at the original image it is very expressive and full of angst! I left those images of how we had mistreated penguins, like the Digestor and the Egg Collector until the very end when I could summon up the will to re-engage with them.

How do you envision the future for penguins?

Peter: For many species, it is a worrying time. Several are on the brink of extinction; some, like the emperor and chinstrap, are on a worrying trajectory caused by climate change that can only be solved at a global level. But there is hope. So far, we have not made any species of penguin extinct and there is still time to save all of the wonderful types of these birds, but the window for doing that is growing narrower every year.

What are the most important impressions you would like the reader to be left with after reading “The Penguin Book of Penguins”?

Peter: We hope readers will come to understand how wonderful and loveable these birds are and how invested into our culture they have become. When we think about the future of penguins, it can be a little depressing, but we are not there yet and that future is not yet written. If people care about a subject, then maybe they have it within their power to alter the future so that the worst predictions never come to light. If this book does anything, we hope it will enthuse people to help save penguins.

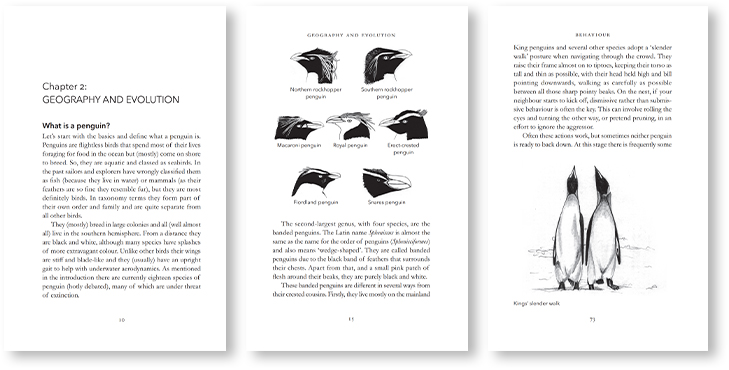

Lisa: I also hope that my illustrations enhance and portray these amazing birds in a true light. I tried to capture their personalities, particularly their behaviour, which I think is absolutely fascinating! The infographics should enable the reader to differentiate between each species, which for some penguin families, especially the banded penguins, is very subtle. I wanted to portray how endearing and intelligent these birds are. They have evolved to survive against the odds and their quirky nature is often fundamental to whether they breed successfully, survive extreme weather conditions and ultimately sustain their populations, and I wanted to reveal these quirks visually to enhance the reader’s experience.

What future research or projects are you planning on currently?

Lisa: I am planning to enhance my penguin illustrations with colour and exhibit them at a number of galleries. I have already been asked to create some other wildlife illustrations for the Arts Society Youth Fund locally, and I hope to illustrate or even write more books in the future.

Peter: I am currently leading multiple projects on penguins and other polar wildlife. My penguin-themed projects include mapping and monitoring seabirds on South Georgia, recording and improving the methods, carrying out population surveys of emperor penguins, and counting chinstrap and Macaroni penguins on the remote South Sandwich Islands. Results from all these studies should be coming out over the next year.

The Penguin Book of Penguins is available as a limited edition signed hardback book, while stocks last, from NHBS here.