COP26, the 26th annual summit of the United Nations climate change conference, is currently taking place in Glasgow. In this article, Hana Ketley looks back over the first week of COP26 and discusses the key pledges and targets that have been announced so far.

Emissions targets

Ahead of COP26, many countries announced new emissions targets, including India, which aims to halve its energy emissions by 2030 and reach net zero by 2070, and Nepal, which now aims to reach net zero by 2045. Net zero refers to a balance between the amount of greenhouse gas emissions emitted and removed from the atmosphere, and according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°, the world must reach net zero by 2050 to limit global average temperatures from rising more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Several countries have committed to meeting this target, with 80% of the world’s economy now striving for net zero emissions. Many of these targets, however, are under discussion, in policy documents or as proposed legislation, rather than being enacted into law. Additionally, several countries have not updated their targets, such as China, which continues to aim for net zero emissions by 2060, a full ten years after the recommended date. Many climate groups and critics are questioning the validity of these pledges, a theme that continues through many of the outcomes from the first week of COP26. As many of the targets set at previous COPs have not been met, there are doubts that they will be achieved this time.

Furthermore, the Climate Crisis Advisory Group, consisting of 15 of the world’s leading climate scientists, have produced a report warning that achieving global net zero by 2050 may no longer be enough to avoid many of the worst impacts of rising global temperatures. The report, titled ‘The Final Warning Bell’, was released in August 2021 and builds upon the most recent report from the IPCC’s Working Group 1, which was released earlier in the same month. Using the IPCC’s insight, the Climate Crisis Advisory Group determined that meeting the 2050 target will only result in a 50% likelihood of preventing average global temperatures from exceeding 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. They suggest that aiming for net-negative emissions by 2050, rather than net zero, will provide countries and industries with the best chance of curbing global warming. Only two countries, Suriname and Bhutan, have achieved net zero (based on self-assessment) and only a few others, such as Finland, Germany and Sweden, have net zero ambitions that are set to be met before 2050. As a result, current global objectives are unlikely to fulfil the proposed target set by the Climate Crisis Advisory Group.

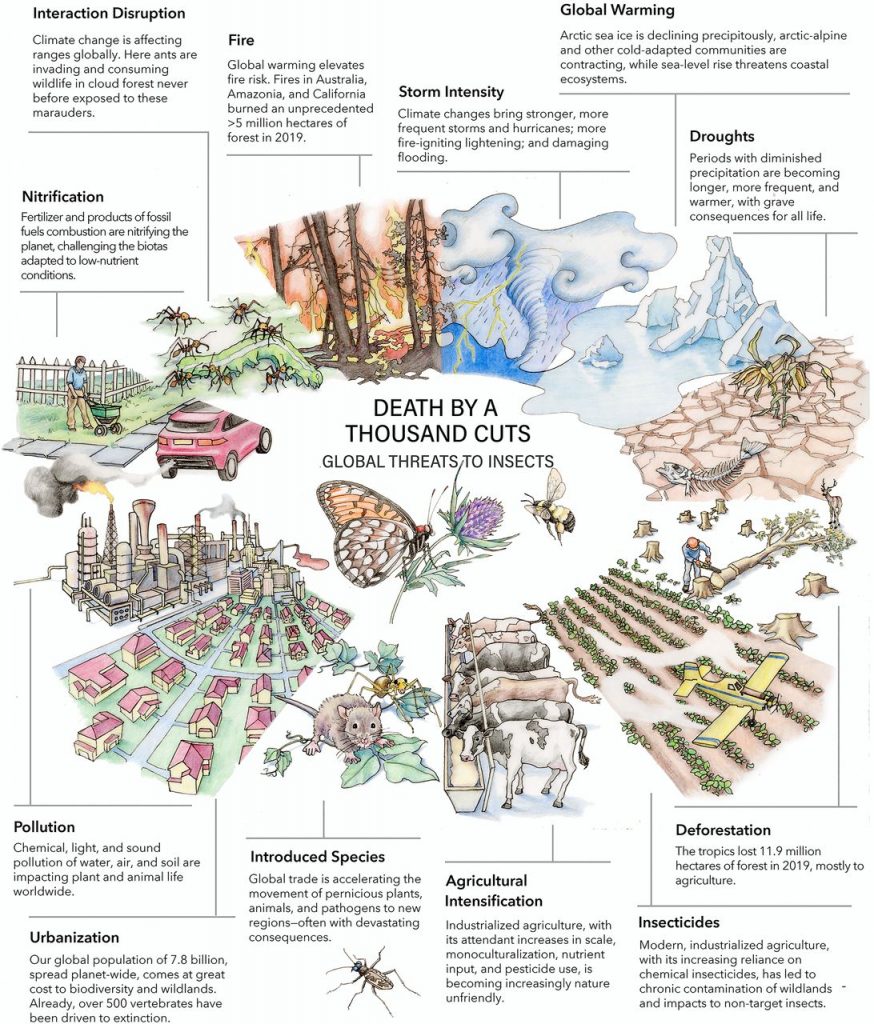

Deforestation

The Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forest and Land Use, which aims to cease and reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030, was one of the first major pledges made during COP26. This historic pact was signed by nearly 130 world leaders, and has been hailed by some as the summit’s first big achievement. As the countries that signed are responsible for roughly 85% of the world’s forests, this pledge might have a considerable influence on deforestation and climate change if it results in effective action. Alongside this commitment, 12 nations, including the UK, U.S., Canada, France and Germany, have also collectively pledged to mobilise £8.75 billion of public funding over the next five years. This fund will be utilised by developing nations for a variety of schemes, including supporting the restoration of degraded land, combating wildfires and defending the rights of indigenous communities. This is backed by the commitment of more than 30 major financial institutions, such as Axa and Aviva, to look at eliminating commodity-driven deforestation from their investment and lending portfolios by 2025. They have also agreed to several other stipulations, including assessing the amount of their investments that are linked to deforestation by the end of 2022. By the end of 2023, they must disclose this information and their mitigation efforts and, by 2025, publicly report credible progress on their goals.

But, due to a lack of detail on enforcement, these pledges on deforestation have already been criticised. The success of this summit and the fight against climate change will be determined by how well all the pledges launched and signed during COP26 are implemented. Many signatories have not specified how this implementation will be monitored, nor has it been defined how countries will be held accountable if they fail to follow through on their commitments. Many critics point to other pledges to reduce or halt deforestation that have not been fulfilled, as many voluntary pledges, such as the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests, have failed to deliver on their promises. One of the key goals of the 2014 pledge was to reduce the rate of forest loss globally by half by 2020, but the rate of tropical primary forest loss has actually increased since the signing.

When questioned about the reality of meaningful action and willingness to halt deforestation by countries that have signed this pledge, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson indicated that the emphasis may be placed on the financial sector. During the press conference on 2nd November, he suggested that these goals would most likely be reached through the “agreement of companies around the world that they will no longer support or invest in these communities”. He also suggested, however, that the pressure on these banks, financial institutions and companies to meet their promises will come from consumers. This is similarly reflected in the proposed Treasury rules, which would require most large UK corporations and financial institutions to release a detailed public plan by 2023 outlining how they will transition to a low-carbon future in line with the UK’s net zero 2050 target. Any commitments suggested by these companies would not be made mandatory by the UK government, as these rules only aim to increase transparency and accountability. Consumers must once again be relied upon to exert pressure on these firms to make serious changes. There are strong criticisms for this lack of regulation by the government, with many arguing that, without legal obligations, these pledges are doomed to fail.

Methane

More than 100 world leaders have also signed the U.S. and EU-led pledge to reduce methane emissions by 30% over the next decade from 2020 levels. Methane has a higher heat-trapping capacity compared with carbon dioxide but breaks down in the atmosphere considerably faster, and so it is hoped that cutting methane emissions could have a rapid impact on limiting global warming. The Global Methane Pledge was first announced in September and it now has half of the top 30 methane emitters as signatories. Critically, however, China, Russia and India, three of the top five emitters, have not yet signed on. Australia, which is among the top ten emitters, has also refused to sign. In 2018, these four countries emitted 2.894 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent, accounting for around 35% of the global total of 8.175 million tonnes (calculated from data sourced from The World Bank, sourced from CAIT data: Climate Watch). The countries that have signed up constitute “nearly half the global methane emissions”, according to Biden, but the pledge’s impact may be limited without the backing of these large emitters.

Further pledges

Other important key pledges and outcomes from the first week include:

- The Breakthrough Agenda, an international plan launched by the UK to help deliver clean and affordable technology everywhere by 2030

- The Global Energy Alliance, a group of philanthropic foundations and international development banks that announced a $10.5 billion fund for emerging economies to switch to renewable energies, with the goal of raising $100 billion in public and private capital

- The Coal Pledge, which has been signed by more than 40 countries, pledging to end all investment in new coal power generation and to phase out coal power in the 2030s for major economies and the 2040s for developing economies. Around $18 billion has been pledged to assist this transition. Notably, China and the U.S., two of the biggest coal-dependant countries, have not signed up.

These, as with all other pledges launched and signed during COP26, will only have a significant influence on our fight against climate change if they are effectively implemented and translated into tangible action. While there is cautious optimism that the pledges and targets announced during the first week of COP26 could be sufficient to keep global temperatures from rising by more than 2°C, there are mounting concerns that they may not be enough to keep the rise below 1.5°C. The head of the International Energy Agency (IEA) has stated that these new promises could reduce projected global warming to 1.8°C. This is better than the prior predictions of 2.4–4.8°C, based on high-emission scenario SSP5-8.5, but it is still above the Paris Agreement’s desired 1.5°C limit. A rise above 1.5°C will most likely see a worsening in the negative impacts on resources, the intensity and frequency of extreme events, ecosystems, biodiversity, lives and livelihoods, making adaptation to climate change much more difficult.

References and useful resources

IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., et al. (eds)]. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 32 pp. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/

A news report on the countries that are now aiming for net zero: https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2021-11-01-80-world-economy-now-aiming-net-zero-not-all-pledges-are-equal

Net Zero Tracker, showing the target year by country and information on their status in law or policy, presence of a detailed plan, reporting mechanism, use of international offset credits and greenhouse gas coverage: https://zerotracker.net/

A news report on the Climate Crisis Advisory Group’s August report on the aims for global net zero by 2050: https://www.edie.net/news/9/Go-beyond-net-zero-and-target-net-negative-emissions–climate-scientists-urge/

The Climate Crisis Advisory Group, 2021. The Final Warning Bell. [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354144163_The_Final_Warning_Bell

The COP26 website information on the Glasgow Leader’s declaration on forests and land use: https://ukcop26.org/glasgow-leaders-declaration-on-forests-and-land-use/

The UK Government’s press release on the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/over-100-leaders-make-landmark-pledge-to-end-deforestation-at-cop26

World Bank’s data on methane emissions: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.METH.KT.CE?end=2018&most_recent_value_desc=true&start=1970&view=chart

The UK Government’s Press release on the new Breakthrough Agenda: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/world-leaders-join-uks-glasgow-breakthroughs-to-speed-up-affordable-clean-tech-worldwide

The New York Times report of the Global Energy Alliance: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/03/world/europe/global-energy-alliance-fund-cop26.html

The Guardian news report on the Coal Pledge and its criticisms: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/03/more-than-40-countries-agree-to-phase-out-coal-fired-power

Comments by the head of the International Energy Agency on the impacts of pledges made this week at COP26: https://news.sky.com/story/cop26-climate-pledges-could-limit-projected-warming-to-1-8c-says-energy-agency-boss-12459562

IPPC. 2021. Future Global Climate: Scenario-Based Projections and Near-Term Information. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/