Our readers may be familiar with you as the director of the 1979 film, Tarka the Otter, so your conservation credentials go back a long way. What first stirred you to get involved with the plight of our wildlife?

Our readers may be familiar with you as the director of the 1979 film, Tarka the Otter, so your conservation credentials go back a long way. What first stirred you to get involved with the plight of our wildlife?

In the late sixties I made several films for the Midland Bank showing the advice they gave to farmers enabling them to reorganize their farms, specialize and make them more profitable. This always involved pulling out hedgerows, filling in ponds and knocking down old barns. Not very good for wildlife. I tried to get them to make a conservation film but they were not interested. In 1970 I met Henry Williamson, who wrote Tarka the Otter, and asked him if he’d be interested in writing a film for the BBC Natural History Unit called “The Vanishing Hedgerows”. The film would be based on his experience of farming in Norfolk between 1936 and 1946. Farming with horsepower initially, then the first tractor and finally pesticides. Running through the film was the story of the plight of the Grey Partridge. The film was a great success and won a conservation prize at the Montreux film festival.

Your new book, A Sparrowhawk’s Lament, explores the state of Britain’s birds of prey. How are they getting on, and what are the main threats to their survival?

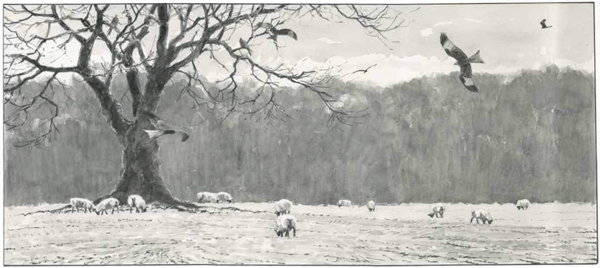

The Hen Harrier’s existence as a British breeding bird of prey hangs in the balance. The main threat is persecution by gamekeepers on grouse moors. It is coordinated throughout the Pennine chain. All predators, not only Hen Harriers, are exterminated. As a result there was no successful breeding in 2013. There is a chance that prospects may improve in 2014. Nevertheless this spectacular bird must not be allowed to become extinct as a British breeding bird. It is estimated that there is territory for up to 300 pairs of Hen Harriers on the Pennine chain. Poisoning of birds of prey is still prevalent throughout the British Isles. Red Kites, Golden Eagles and Common Buzzards are the main targets.

Did you spend much time roaming the countryside encountering these magnificent birds during the research process of the book? You must have met some interesting human characters too on your travels?

I spent three years researching and writing A Sparrowhawk’s Lament. Some of it came out of films I had made for the BBC and Channel 4. For instance I made 3 films on the Peregrine Falcon: one in Scotland, two in Cornwall. On them I worked with two experts, Roy Dennis in Scotland, and the late Dick Treleaven in Cornwall. I did travel to Scotland to meet up with Roy Dennis and glean some of his vast experience with Ospreys and Golden Eagles and I went to Mull to talk to Dave Sexton about the successful re-introduction of the White-tailed Eagles in Scotland. In the North of England I saw Merlin and Honey Buzzards and I talked to my cousin George Winn Darley who owns a grouse moor. Stephen Murphy of Natural England showed me round the Forest of Bowland which was once the stronghold of breeding Hen Harriers. There I was priviledged to hear his first hand account of the death of Bowland Betty. In the Midlands I met Tim Mackrill who took over the Osprey re-introduction at Rutland Water. Nearby at Rockingham I spent time with Steve Thornton and Derek Holman who’d been involved with the Red Kite release on the Forestry Comission land there. They also showed me nesting Hobbys at Lilford Hall. In Norfolk there was plenty of opportunity on our Hawk and Owl Trust reserve to see Marsh Harriers, Goshawks and Sparrowhawks. David Lyles showed me where to watch nesting Montagu’s Harriers on his land. On Salisbury Plain I met up with Nigel Lewis and watched him ringing young Kestrels and in the West Country Robin Prytherch took me round his Common Buzzard study area in the Gordano Valley near Bristol. Finally, Steve Roberts blew away some of the mysteries surrounding that extraordinary bird, the Honey Buzzard.

I also talked to a great number of wildlife cameramen. Mike Richards, Hugh Miles, John Aitchison, Simon King, Chris Knights, Martin Hayward Smith and Manny Hinge shared their often gruelling experiences with me.

Finally, there were many enthusiasts, amateur and professional who took time to talk to me and impart their knowledge. In particular, I must mention the late Derek Ratcliffe, Robert Kenward and Ian Newton.

What is the significance of the title A Sparrowhawk’s Lament?

As a film maker I was always keen to find a hook to catch the audience’s attention. If you didn’t they had the easy option of switching off. So before I wrote a word I knew I had to have a hook. Quite by chance I found my hook while I was in hospital for an operation. I was literally waiting to go down to the theatre when my wife came in with an armful of books for me to read. One of them was the Penguin Book of Bird Poetry. My wife left and I flicked through the pages. To my amazement I found an anonymous fifteenth century poem in which a male Sparrowhawk was complaining that the fear of death worried him. In the fifteenth century Sparrowhawks were protected – they were the hawks that a holywater clerk was allowed to fly. Did the Sparrowhawk have a crystal ball to forsee the future – persecution and pesticides? So that was the hook and the first chapter is a detective story seeking out from what it was that the male Sparrowhawk was fearful of dying.

How has our relationship with birds of prey changed in this country over the centuries?

For over three thousand years Man trained birds of prey to put food on the table. With the introduction of the double barrelled shotgun that relationship was severed. The 1831 Game Act let loose a period of persecution beyond belief. By 1916 five birds of prey were extinct in the British Isles – the Goshawk, Marsh Harrier, Osprey, Honey Buzzard and White-tailed Sea Eagle. Gradually, the swell of public opinion, nauseated by this senseless, selfish slaughter, held sway. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds was formed and the Wildlife and Countryside Act of 1981 afforded full protection for all British birds of prey. In recent years the BBC TV programmes, Springwatch and Autumnwatch, have gone to great lengths to champion the role of birds of prey in our environment and to show in a sympathetic way the difficulties they experience in finding a mate, nesting, providing enough food for their offspring and finally in migrating to their winter quarters.

What are the current priorities now for conservation of our birds of prey, and how might this book inspire people to get involved?

The top priority at the moment is to ensure that the Hen Harrier does not become extinct as a breeding bird in England. It is on a knife-edge at the moment. Publicise the horrific cruelty of pole traps and poisoning. We need more Wildlife Crime Police Officers. We need to strengthen the law so that landowners are made to accept the responsibility for any crime against birds of prey that occurs on their land.

The Sparrowhawk’s fear of death in that fifteenth century poem, which I have called A Sparrowhawk’s Lament, inspired me to find out the true state of British breeding birds of prey, exactly how they were faring. I hope that some of the experiences that I have had will influence young and old to revere our birds of prey and join an organisation such as the Hawk and Owl Trust which are dedicated to the conservation of all birds of prey. They are thrilling birds. Whether you revel in the sky splitting stoop of the Peregrine or the ground hugging dash of the Sparrowhawk the world would be a poorer place without them.