Emilian Stoynov and colleagues created the Fund for Wild Flora and Fauna (FWFF) in Bulgaria in 2000 to support a project to reintroduce griffon vultures in the country.

Emilian Stoynov and colleagues created the Fund for Wild Flora and Fauna (FWFF) in Bulgaria in 2000 to support a project to reintroduce griffon vultures in the country.

Emilian has been involved with vultures for many years and in 2007 won the Whitley Award for work with reducing the threat to wolves, bears and vultures from humans and poison in Bulgaria.

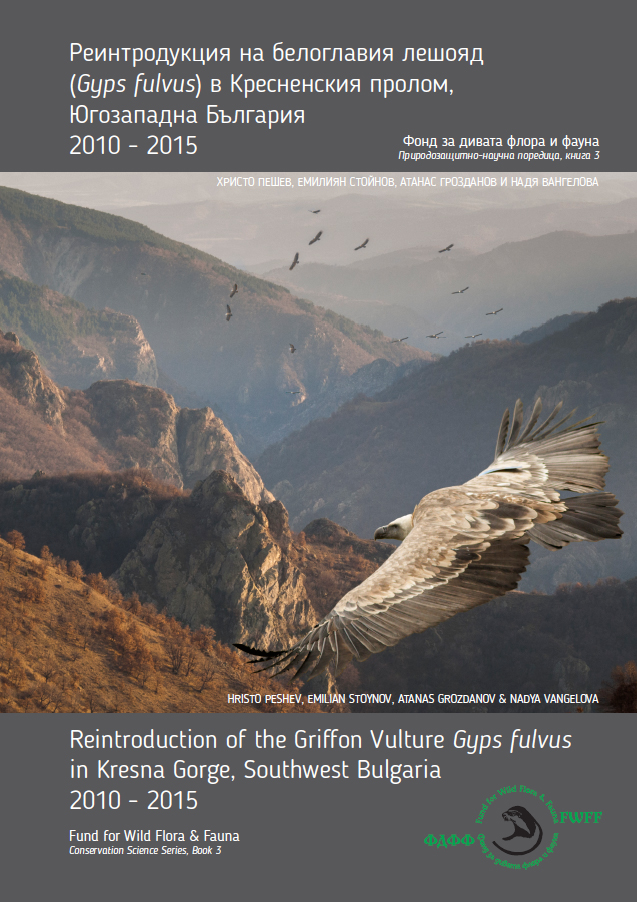

A book summarising the griffon vulture reintroduction process from 2010 to 2015 has just been published.

How did you become interested in working with vultures, and how did you come to be a part of this reintroduction project?

When I was a child I was interested to explore nature. At that time there was not much literature to find and to learn about nature. First I wanted to work on plants. Just around 1985 the first edition of the Red Data Book of Bulgaria was published and I tried to buy a copy and start studying the species. But when I had enough money from my parents and relatives around New Year’s Eve, I did not succeed to find the Volume I of the book- plants. I found after checking a lot of book stores in Sofia the Volume II- animals. It was only one copy of the book and part of it was missing (reptiles and amphibians), but the birds were there. I found that some of the rarest birds were the vultures and they were historically found in the area of my father’s birth town – Kotel. Here I started to wish to meet vultures in nature. After some time I became a member of Bulgaria Society for the Protection of Birds (BSPB) – now BirdLife Bulgaria – which was just established and was in charge of the conservation of last colony of griffon vultures in the country in the Eastern Rhodope Mountains. I was first a volunteer and later was working for the project for conservation of vultures in this area. Then I started to think about restoring the population in other sites in Bulgaria. I tried to organize feeding sites in other parts of the country where vultures historically were present, but this was not enough to restore the old colonies. Then I saw what was done in Massif Central in France by Michel Terrasse and his colleagues from FIR/LPO– namely reintroduction of griffon vulture through release of captive bred but also rehabilitated birds from Spain. Thus I decided that this should be done also in other parts of Bulgaria. BSPB were not very willing to work on reintroductions, which is why it was necessary to create a new NGO to work on reintroductions – Fund for Wild Flora and Fauna (FWFF) – created in 2000. Then I married Nadya Vangelova- and we went to live in her town – Blagoevgrad. The nearest historical place for vultures was Kresna Gorge (only 25 km away from the town) and it appeared it was still suitable for vultures, but they were gone extinct in the 1960s due to a mass and well organized state level poisoning campaign targeting terrestrial predators. Ten years later after the establishment of FWFF we succeed to implement the reintroduction of the species in Kresna Gorge, which is now presented in the current book.

Tell us about the Kresna Gorge in terms of biodiversity – what sort of place is it, and how do vultures fit into the ecosystem?

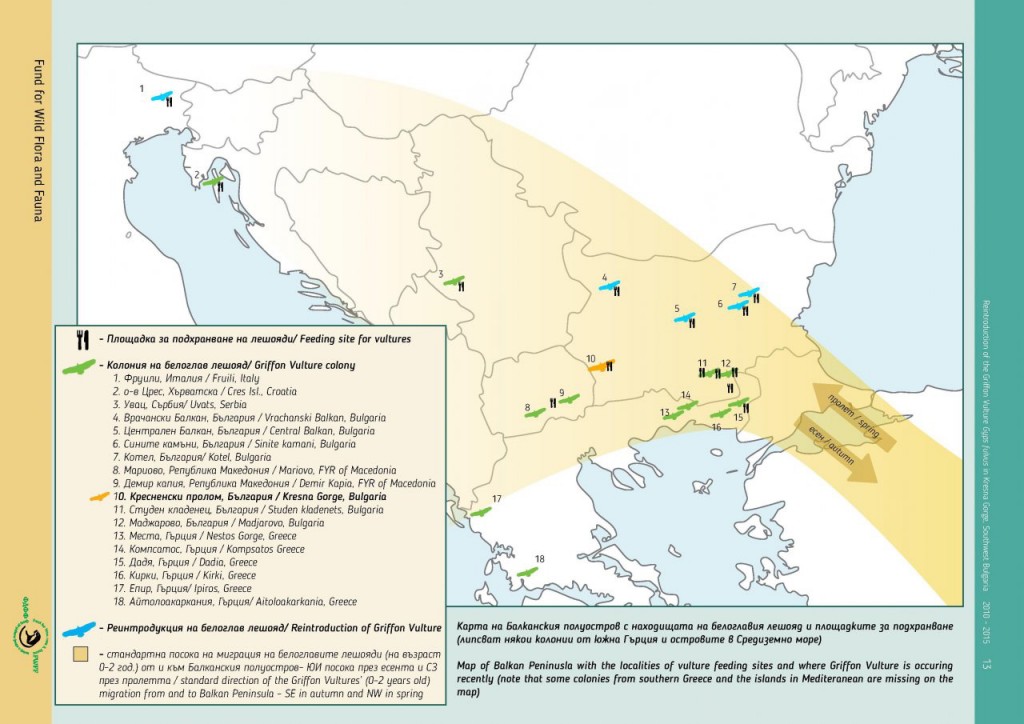

The Kresna Gorge is one of the very few places in Bulgaria with Mediterranean climate. This, in combination with steep slopes and rocky outcrops, makes the area very interesting for biodiversity. Some species of Bulgaria’s reptiles are found only here. Autochthonous loose forests of Juniperus excelsa were declared nature reserve and many southern species of birds are found here. In terms of vultures’ suitability, the area still has well preserved extensive livestock breeding and transhumance practice, where the herds are moved in the nearby high mountains Pirin and Rila, home to two of the three national Parks in Bulgaria. So it is the combination between deep valley with mild winters and high mountains with alpine pastures that makes the habitats suitable for vultures. Extensive livestock breeding and the presence of large carnivores like wolf and bear are additional benefits for the vultures. The last also poses a threat for the vultures, because the conflict between livestock breeders and carnivores some times leads to illegal poison baits use, which is the biggest threat for the vultures. We found that providing the feeding sites for vultures make it safer for them. Also, some people are concerned that it may be unnatural to feed vultures but because we dispose mainly of – although not only – food coming from the nearby villages, this makes the process rather natural.

Why was there a need to embark on a reintroduction process – how did the griffon vulture lose its place?

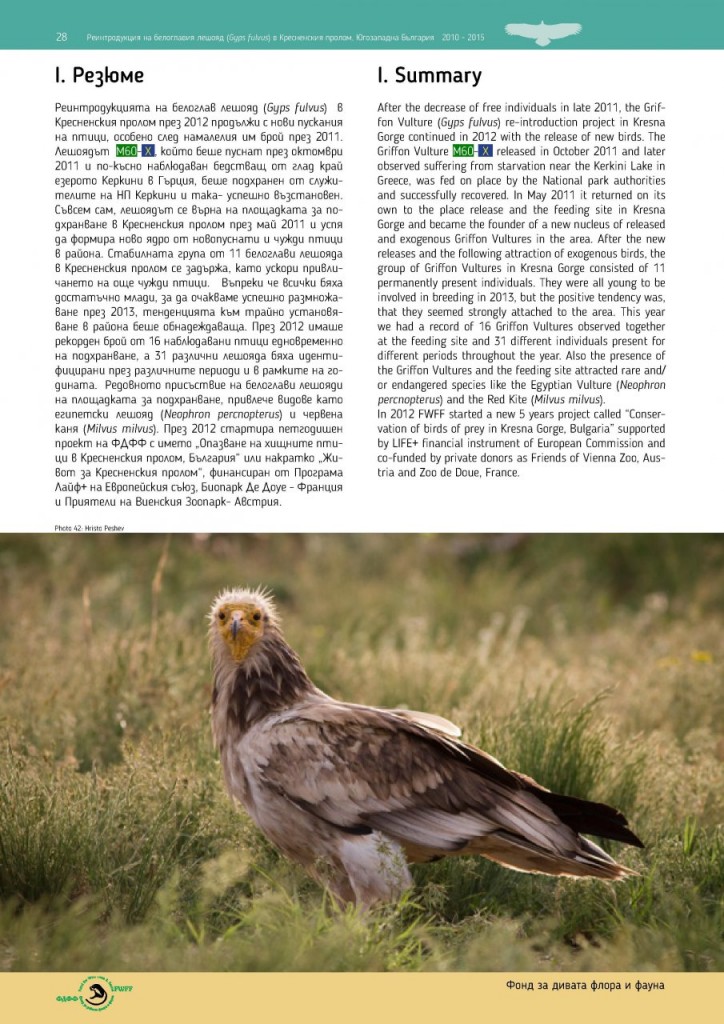

Since the beginning of the twentieth century the situation of the vultures of the Balkans and Europe became worse and worse based on extensive livestock breeding decline but mainly on direct persecution and non-deliberate poisoning. Not least the habitats changed especially in Bulgaria, where vast areas were reforested and thus the vultures no longer were able to search for and find food. In the 1960s nearly every available carcass for the vultures was poisoned and they went extinct from the entire country. In 1970 all large European vultures were considered extinct from the country. Only a small colony of less than 30 birds and 2-3 breeding pairs survived in Eastern Rhodope Mountains on the border with Greece. Although the conservation measures helped this colony to increase from 2-3 pairs to about 80 nowadays, the range of the species did not extend and still is only in Arda River Valley in Eastern Rhodopes. In the 1970s the large vultures were still surviving in Greece, but with time the bearded and griffon vultures have gone extinct from the mainland. The only black vulture colony in the Balkans is found in Dadia National Park in Greece close to the Bulgarian border. So we saw there is now suitable source of vultures where from they may recover naturally and that is why we decided to establish 5 new colonies – 4 to the north along the Balkan Mountain chain where we work in close cooperation with other NGOs such as Green Balkans and Bird of Prey Protection Society, and to the south west, Kresna Gorge. The last is also close to the small and declining population of the griffon vulture in FYR of Macedonia. But with the newly established colonies, it seems the situation gets a bit stabilized now. The summering, wintering and migrating birds on Balkans now have some more safe areas – read the book for the Reintroduction in Kresna Gorge to find how it works.

In short – if we want to have forests, wolves, but also vultures we have to reintroduce and organize feeding sites for them in our modern world dominated by man.

Reintroductions are quite a hot topic at the moment. One of the main concerns is finding accord between conservationists, landowners and the public regarding the benefits of such actions. Was this a problem for you in Bulgaria?

This is manageable. Especially with friendly species like the vultures it is a small concern for the local people in the very beginning and then they just appreciate the lovely and gorgeous birds flying high in the sky. The proper communication and involvement with local people is crucial for the success of any such initiative.

What are some of the major challenges the team faced during the years of the project?

The development of the network for receiving in-time information about livestock carcasses was very important and it took quite some time. Establishment of the first nucleus of griffon vultures also was a challenge. We did it twice until we found what the most important thing is. It was the food that should be provided not only in large quantity, but also at the best place for the vultures, and in summer to be provided frequently in small amounts so as not to decompose. We hardly learned that decomposed carcass is not an appreciated food source for vultures. They prefer fresh carcasses. Or at least not rotten meat. When we found that and made an effort to overcome it we saw the success.

Would you say that the process has been a success, then?

Yes, this is a success story. Of course we would like to see some more achievements in successful breeding and increase of the number of the breeding pairs of griffon vultures, as well as the return of the black and Egyptian vultures as breeders in the area. And one day also the return of the bearded vulture too.

Are there any lessons learned from this project that might have application for reintroduction practice in general?

There are two things: the vultures will not survive in the modern world without managing the carcass disposal. We could not have forests and wolves and also to have vultures just on their own. The last should be supported through feeding sites, at which the carcasses from the local villages and farms would be disposed and made accessible to vultures.

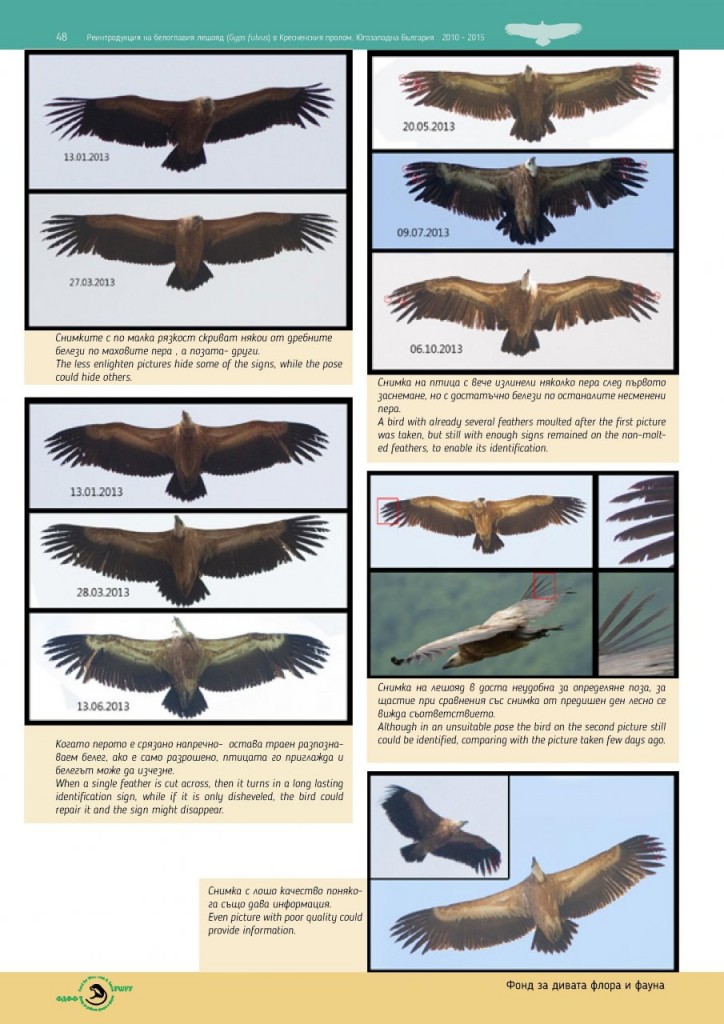

We developed a good method for individual identification of the vultures through so-called visual marking. We use cameras with long lenses and take pictures of every bird seen in flight. Then we compare the characteristics of the plumage. This way, even birds not marked with rings or wing-tags could be distinguished. The method is well described in the book.

If you could make one change to policy in Bulgaria, or beyond, that would be of benefit for vulture conservation, what would it be?

In the vultures’ range (either historical or current), where suitable habitats are still found, every natural or national park authority should be involved in maintenance of feeding site(s) for vultures. This should be one of the basic management practices for all protected areas that have an administration body. This way a large network (e.g Natura 2000 sites) of vulture safe areas will be established and the coherence of the habitat and space restored.

Some adaptations of the legislation concerning poisoning of wildlife and domestic cats and dogs should be done especially in Bulgaria. The use of poison baits in natural environment should be treated as an act of hunting. Nowadays the Bulgarian legislation does not treat the poison bait setting for dogs and cats. Only if a game species and/or protected species is affected the law could be applied.

How are the vultures doing today, and what are the next steps, for the project, and your own work with the Fund for Wild Flora and Fauna?

The vultures are preparing for the new breeding season. They are now making the very attractive simultaneous flights as breeding displays and seem very much enthusiastic especially in warm and windy days.

The next step is the reintroduction of the Eurasian black vulture, within the frame of the new Bright Future for Black Vulture in Bulgaria project LIFE14 NAT/BG/649, in cooperation with Green Balkans, Vulture Conservation Foundation, EuroNatur and the regional Government of Extremadura. I hope in future a similar story and a book will be issued for the black vulture in Kresna Gorge and Balkan Mountain in Bulgaria, where the species is now extinct for more than half a century.

I would like to mention here my colleagues and friends that work hard for all this to happen – Hristo Peshev, Lachezar Bonchev, Atanas Grozdanov, Nadya Vangelova and Yavor Iliev.

![Reintroduction of Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus in Kresna Gorge, Southwest Bulgaria 2010-2015 [English / Bulgarian] Reintroduction of Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus in Kresna Gorge, Southwest Bulgaria 2010-2015 [English / Bulgarian]](https://blog.nhbs.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/vultures-internal.png)