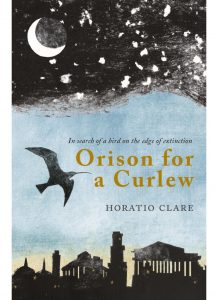

Orison for a Curlew takes us on a pilgrimage in search of the slender-billed curlew; once a common sight in its breeding grounds of Siberia, but now diminished to a handful of unconfirmed sightings. In this article, one of our book team Nigel Jones, talks to the author, Horatio Clare, about conservation, environmentalism and his hopes for the future of the titular bird.

Despite the rather gloomy prognosis for the fate of the slender-billed curlew, your book seems to me about hope. Are you optimistic that conservation will gain ground due to stories such as the plight of Numenius tenuirostris, or do you think this story is more of a prelude of things to come?

It is about hope. I do think the hunger for watching nature footage, and writing and reading about the natural world will translate, given the unavoidable nature of climate and environmental awareness as the world changes, into action. My sense of my generation, currently in our forties, is that we came out of an easy time – the nineties – well aware of how lucky we were, and how things were going with the planet and capitalism generally – and that we have not seen the best of us yet. We have been getting it together, I know of great people in powerful positions, and others doing tremendous work, and I hope things will change for the better. Brexit and Trump are shattering reversals for the world and nature, but not insurmountable. Moreover, it seems the slender-billed curlew may not be on the way out! A population may breed in Kazakhstan and the birds may have been seen and filmed a few years ago in Holland.

Being such a delicate and ethereal creature; do you think the slender-billed curlew was always vulnerable to possible extinction, regardless of human activity; was there a more dominant species pushing it out of it’s niche?

No I am sure we are the dominant species which pushed it out, by draining marshes and polluting the water. It was surely vulnerable in that it is highly specialised.

The relentless corrosion of diminishing natural spaces is a strong theme in your book. The argument for development is usually ‘people come first’ and, by definition, wild spaces are mainly unoccupied by people. I would love to see the hundreds of white pelicans, spiralling up to find the thermals that you describe. However, most of us will only see a spectacle such as this on television, or envisage it vicariously. For me this is the paradox of conserving wild spaces for their own sake – how do we get everyone involved with conservation when only a few people ever get to experience what it creates? How do we make wild spaces matter to everybody?

The relentless corrosion of diminishing natural spaces is a strong theme in your book. The argument for development is usually ‘people come first’ and, by definition, wild spaces are mainly unoccupied by people. I would love to see the hundreds of white pelicans, spiralling up to find the thermals that you describe. However, most of us will only see a spectacle such as this on television, or envisage it vicariously. For me this is the paradox of conserving wild spaces for their own sake – how do we get everyone involved with conservation when only a few people ever get to experience what it creates? How do we make wild spaces matter to everybody?

Knowledge of the natural world and knowing what you are looking at can make a walk in the garden, park or road a safari. That is the way you make every space matter: put names and stories on the creatures that inhabit it. Funnily enough I have written two children’s books on the subject! Which makes me think, children’s literature being a kind of menagerie, we all begin as nature-lovers; it’s just that some adults discount the planet’s marvels, and certainly its needs. And of course corporations exist solely to harvest the planet’s riches as quickly as possible, heedless of environmental cost, if they are allowed to be, for the benefit of share-holders. I think some form of cooperativism between individuals and between nations offers the only hope for long-term sustainability.

There are some conservationists that advocate adopting a more laissez-faire approach to extinction, moving priorities to bio-abundance rather than biodiversity and accepting that extinction and invasive species are part of the evolutionary process. What are your thought regarding this way of thinking?

It is a sin to cause the extinction of a species, as Prof Kiss puts it in Orison. To fail to prevent the extinction of a species seems of a different order, if hard to enjoy. If you regard our privilege of dominance as responsibility, then we have a duty to look after all of what used to be called God’s creatures. We should not really accept anything less than bio-abundance and biodiversity, should we?

I really enjoyed meeting all the people in your book; their dedication, passion and commitment to the cause of conservation was wonderfully described, without ever reducing them to parodies or caricatures. For me they represented the ‘hope’ in your book. However, they all seemed at odds with the world, probably viewed by their relative governments as part of an ‘awkward squad’ and their work and funding was often in decline. What would you say to inspire a future generation of conservationist to take up the baton?

With journalism going through tough times, there is no better way to have the fun and the interest of being the awkward squad, travelling the world, getting up the noses of baddies and making the planet a better place than becoming an environmentalist! What a blessed and admirable profession! What adventure it offers! And…the happiest people you meet are naturalists and environmentalists, on the whole, though they deal in tragedy and folly often.

The hunting for sport, the mist nets and the bird markets make for a very threatening environment for migrating birds. However, it’s the drainage of the marshes for agriculture and the encroachment and contamination of heavy industry that you more frequently allude to as the biggest threat. Do you see hunting as a potential partner to conservation, or are those two pursuits always going to be in conflict?

Having just read Bowland Beth: The Life of an English Hen Harrier by David Cobham I feel hunting is unhelpful, if not abominable, but that may be a grouse-centric view. In Greece the numerous hunters are thought of with something like revulsion by some conservationists; the hunting I saw while living in Italy was an absolute disgrace. No doubt many hunters are great and ardent conservationists. Unfortunately many are not.

The slender-billed curlew sightings in recent history are difficult to verify. What are your hunches about their authenticity and when was the last recorded sighting that you believe was accurate?

The birds filmed in Holland in 2013 seem genuine but I am no expert. I believe they are seen – and recorded – now and then. I heard a report from Oman, but a confirmed sighting is a tricky thing: it seems you need two or more photos and absolute proof. My friend Istavan Moldovan is cautious about the 2013 footage – as I write he is chasing relict populations of Apollo butterflies in the Carpathians in Romania. Does that not sound like a great career?

The last question is a simple one, but maybe the most difficult to answer. I know you certainly hope so, but do you believe Numenius tenuirostris will ever be seen again?

I absolutely do. I am quite sure they are out there and it is my dream to see one! Thank you so much for your wonderfully intelligent and acute questions, quite the best!

Orison for a Curlew, written by Horatio Clare and illustrated by Beatrice Forshall, is published by Little Toller Books and is available in paperback and hardback.

Little Toller was established in 2008 with a singular purpose: to revive forgotten and classic books about nature and rural life in the British Isles.

Their Nature Classics Library series was established to re-publish gems of natural history writing, with up-to-date introductions by contemporary writers. The success of the series has now developed into a publishing programme which includes a series of monographs by authors like Fiona Sampson, John Burnside, Iain Sinclair and Adam Thorpe as well as stand-alone books – all attuned to nature and landscape and aimed at the general reader.

Each Little Toller writer brings something new to the series – but it’s always characterised by a deep understanding of the subject, combined with wonderful writing. A sense of the personal reaction to the natural world is imperative. Little Toller also pay a great deal of attention to the aesthetic of their books, using artists to complement the writing to create a beautiful object, befitting Little Toller’s high publishing standards.

Little Toller is now preparing its books for the latter part of the year, notably the first ever biography of the legendary but enigmatic J A Baker, author of The Peregrine, and access to the new Baker archive has led to important new insights into his life. 2018 will see new books from Tim Dee on Landfill, a book about Ted Hughes and fishing called The Catch, and an examination of the landscape of the north of the Irish republic from Sean Lysaght. Little Toller’s sister charity Common Ground is also working on a large exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park next year, for which there will be a raft of publishing.