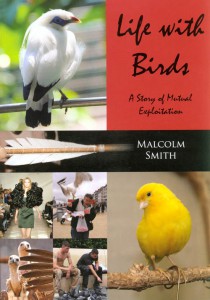

New from Whittles Publishing, Malcolm Smith’s Life with Birds: A Story of Mutual Exploitation zips around the world picking up sublime and ridiculous, sobering and frivolous facts from all its corners. Truly bulging with bird-lore, this makes for an engrossing read for all ornithology enthusiasts.

What’s your background in the bird world, and how did you first become interested in avian-human mutual relations?

What’s your background in the bird world, and how did you first become interested in avian-human mutual relations?

I think I’ve always noticed bird/human interactions wherever I’ve been – though probably more subconsciously – until I began to think about compiling and organizing them into chapters for the book.

It’s been part of a life-long interest in birds combined with a training as a biologist, though with very limited time to pursue these interests personally when I was Chief Scientist at the Countryside Council for Wales.

From a 10ft high Jackdaw nest at Eton college and the silvery bird trills of Vivaldi’s Flute Concerto in D ‘The Goldfinch’, to the 1,728 word vocabulary of Puck, the world’s most literate budgerigar, it seems there is no bird fact left out. Have you always been an intrepid collector?

Quite the contrary, there are probably just as many examples of bird/human interactions left out of my book! I’ve tried to include examples of all the major ones and many of the more unusual, bizarre and intriguing. But I had to be selective! It would be quite possible to write a whole book on birds inspiring literature and art for example but I particularly wanted to weave an interesting story using a whole range of examples to show how widespread our links are with birds.

While parts of the book have a more light-hearted, even irreverent approach, you do take a serious look at exploitation. How do you see our relationship with birds as we move through these challenging and changing times?

I think most people will continue to be oblivious to birds, almost forgetting that they eat them regularly, make use of their feathers, see them every day on their homes and in their streets, and hear them almost constantly.

I’m pretty sure that more species will take to city life, mostly causing no problems to people. But I think I have probably underestimated the future impact of city gulls – which are taking over from city pigeons – and are likely to cause more and more summer-time injuries by attacking people. Local Authorities will soon be wishing that their docile city pigeons were back! If we don’t want a growing gull problem, we need to keep our streets very much cleaner and food discard-free, something we seem to find impossible.

Human greed knows seemingly few boundaries and it’s easy to get depressed when you witness the illegal wild bird trade first hand. Unless some of the worst offending countries start acting on their international responsibilities, it’s set to continue apace.

You have plenty of interesting stories to tell – are there any bird encounters/tales featured in this book that particularly stand out for you?

Many stand out, particularly those where I had personal experience such as a Parsi funeral or collecting eiderdown from nests. But one story that does stand out particularly is that of Honeyguides leading African tribesmen to wild bee nests. I was able to gather it from a N’dorobo tribesman in northern Kenya via an Italian ornithologist working there who translated his words for me! And next week I join them both in the isolated Mathews forested mountains in Kenya. So I will be able to follow Honeyguides with Robet Lentaaya, the tribesman concerned. It’s a practice that’s dying out.

What was special, too, was the information that he can follow three different Honeyguide species, each with a different call and different response call back from the tribesman. I can’t find any mention of that anywhere in the literature!

If a reader were to take one thing away from the experience of reading Life with Birds, what would you like that to be?

That our lives and theirs remain very strongly bound together, more closely than most people would ever imagine, even in our supposedly advanced western society.