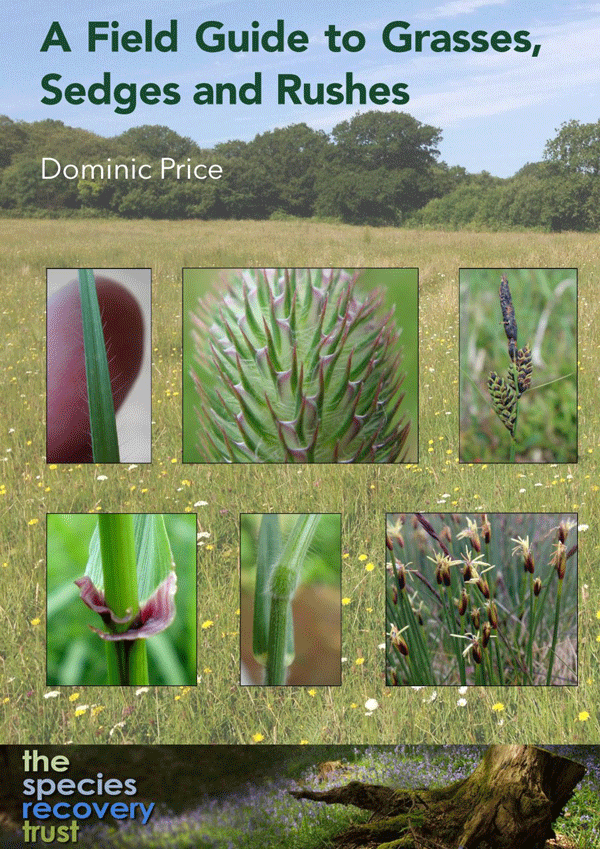

Dominic Price is the author of this summer’s botanical bestseller, A Field Guide to Grasses, Sedges and Rushes. He is also director of The Species Recovery Trust, a botanical tutor, and an all-round advocate for conservation.

Your book is proving to be a huge success – what prompted you to write it, and who is your target audience?

It mostly came about from the grass courses I’ve run for the last seven years, during which I built up a huge body of observational evidence on grasses, from chatting to people and just spending a lot of time looking at them. Teaching plants is fantastic as it really makes you be concise about why things are what they are, plus you get to see what people muddle up; things you might never think yourself.

In addition I felt there was a niche for an affordable, portable, and easy to use book. It definitely won’t suit everyone, but I hope that people who might have been put off by some of the more weighty tomes might find this a good way in (which certainly applies to me). It won’t teach you every grass, but hopefully it will make people feel much more confident about the ones you tend to encounter regularly.

In addition I felt there was a niche for an affordable, portable, and easy to use book. It definitely won’t suit everyone, but I hope that people who might have been put off by some of the more weighty tomes might find this a good way in (which certainly applies to me). It won’t teach you every grass, but hopefully it will make people feel much more confident about the ones you tend to encounter regularly.

How did you become interested in grasses?

During my early years of being a botanist I was terrified of grasses and it took me a long while to get a handle on them. This came about from spending time with other friendly botanists and gleaning as much as I could from them. Once I had got better at them (and I’m still a long way from mastering them) I was really keen to share this knowledge with other people. I did my first grasses course at the Kingcombe Centre 7 years ago, which I was absolutely terrified about running, but it went OK, and it all moved from there. I now run about 18 grasses courses a year, which I absolutely love doing, and all the proceeds from these go into our species conservation programme, meaning a single day’s training can fund a species programme for a year.

What defines the graminoids, and how can the three groups – grasses, rushes, and sedges – be distinguished?

It’s a difficult term, graminoids! I’m very guilty of calling them grasses, which of course only some of them (the Poaceae) are. I also tend to commit the grave sin of talking about wildflowers and grasses (especially when describing courses) when of course grasses are in fact flowers. Their key characters are that they are all monocots, and exclusively wind pollinated.

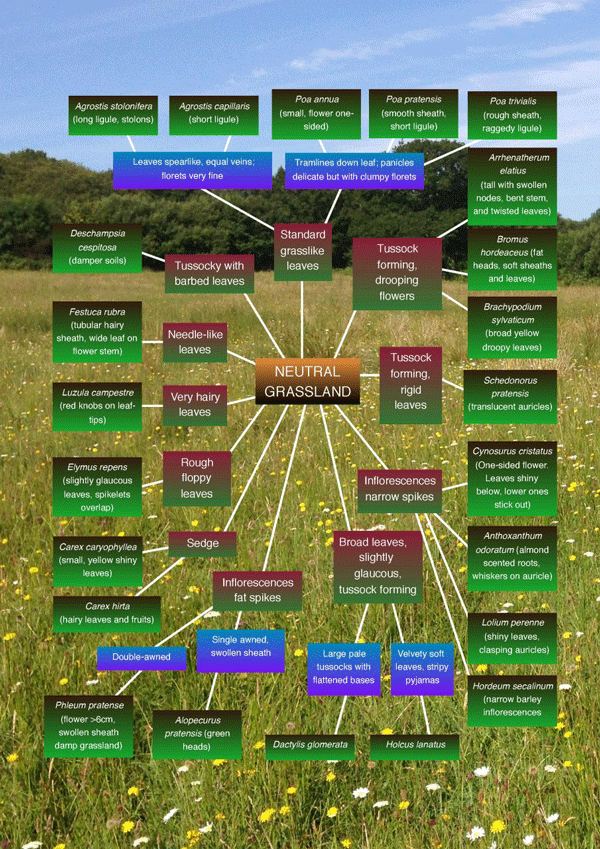

Telling them apart can be relatively easy, the rushes tend to have waxy round stems, the sedges are tussocky with separate female and male inflorescences, and the grasses are, well… grassy looking? But there are so many exceptions to this! Just today I was running a course where someone muddled up Slender Rush with Remote Sedge, and I realised that these two look almost identical from a distance!

What is the importance of the graminoids in the ecosystem at large?

Graminoids are exceptionally useful as indicator species, with many of them showing incredible affinity to certain soil types, nutrient levels and pH. If you walk into a field and see a shiny green swath of Perennial Ryegrass you know you’re unlikely to be finding overwhelming levels of biodiversity. Go into another field and find a clump of Meadow Oatgrass and you know you’re in for a long haul of finding other species.

As it says on the Species Recovery Trust website, over the past 200 years, over 400 species have been lost from England alone. Do you think enough is being done to halt biodiversity loss in the UK?

Tricky question! We have an incredibly large and diverse conservation sector in the UK, full of talented and passionate individuals devoting their lives to saving the planet. And yet we are still losing species at an alarming rate. When I was born, just over 40 years ago, the world had twice as many species as it does now, so this is not a historical problem we can blame on previous generations, this is the here and now of how humans are choosing to live our lives and harm our planet.

These are clearly difficult times financially, and clearly every sector is feeling the pain of budget cuts, however it is upsetting to see the way biodiversity has almost dropped off current political agendas (the environment was barely mentioned at all in the referendum debates) so I do worry that people, and governments, are just not doing enough. It is now fairly widely accepted that we are living through (and causing) a sixth mass global extinction event, which should be the biggest story and policy issue anyone is talking about, and yet species conservation still seems to be a niche market!

What does it take to re-establish a species like Starved Wood-sedge, which is one of the Trust’s Species Recovery Projects?

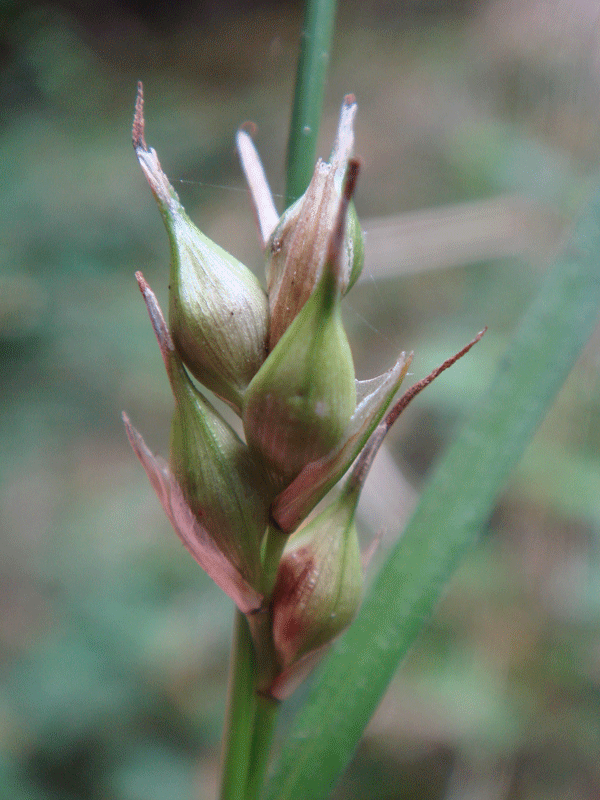

Starved Wood-sedge (SWS) has two native sites in the UK, and we’re working hard at both of these over a long time period to steadily improve the conditions, bringing more light in through coppicing and canopy reduction, and trying to encourage seedling establishment through ground scarification. SWS has an interesting bit of trivia in that it has the largest utricles (seeds) of any native sedges which should make it very easy to grow, but recently we started to think these large seeds may be their downfall as they are so susceptible to vole and mouse predation – but it’s hard to know for sure. We have established and continue to closely work on the two re-introduction sites, where we used plants grown up by Kew Gardens to establish new populations, and we are keen to establish one more in the next decade in a more traditionally managed wood to look at how the species would fare in active coppice rotation.

If you could put one policy change in place today to enhance species conservation what would it be?

I’m not sure, my current rather grassroots view is I’m not sure if conservation isn’t dying a death by policy. A few years back I spent the best part of two years of my life working on Biodiversity Opportunity Areas, only to see these being replaced by IBDAs (which I’ve now forgotten what it stands for) only to see these superseded by NIAs. I then had somewhat of a personal crisis that in all that time, even though I’d been instrumental in producing some very interesting maps of core area and buffer zones and opportunity areas, I’d done absolutely nothing to help species on the ground. I think it was during this same time that Deptford Pink went extinct in Somerset and Dorset too, which I still feel pretty bad about.

The problem with policies, and ministers, and successive governments is that they never last for that long. While not disputing that our current democracy is a wonderful thing, and obviously I feel lucky to live in a country where we can all vote and potentially change things we like, if you superimpose governments and policies on top of the Anthropocene (the current geological age where humans have gained the ability to start fundamentally changing the planet, both in terms of biodiversity and climate) then the two simply don’t match up in terms of the timescales we need to be operating on to bring a meaningful change to biodiversity loss. And it goes without saying that when government budget cuts occur it will always be the environment sector that will suffer, and this obviously has a terrible net effect on projects that are up and running and are suddenly suspended.

Without wanting to sound too ‘big society’ I think the meaningful changes we are seeing are from individuals, either making a big difference in their jobs in the environment sector, or simple volunteering, spending a few days a year clearing bramble from around a rare species, counting butterflies on a transect, monitoring their local bat populations. For me, that is where change is happening, not in government policy units.

How would you encourage a young nature lover or student to take an interest in the subject of grasses?

I’m lucky to have two young children to try this out on, and I must say they are now budding graminologists. I think the starting point is everyone likes knowing what things are and naming them, whether it’s music, works of art, types of lorry. We are on the whole naturally inquisitive beings, so I just tend to show people things and encourage them to go off and find more like them. Add to that some stripy pyjama bottoms (Yorkshire Fog), Batman’s Helmet (Timothy), Floating Sugarpuffs (Quaking Grass) and Spiky Porcupines (Meadow Oatgrass) and the whole thing becomes pretty fun! Incidentally there are equivalent adult versions of these too, which are unmentionable here…

What is the most surprising, odd, or unexpected fact you can share about grasses?

Grasses have a profound link with humanity. 4 million years ago the spread of grasses in the savannas of East Africa is now believed to be the main driver in our primate ancestors coming down from the trees and developing a bipedal habit to move between patches of shrinking forest while keeping a watch out for predators. 40,000 years ago we saw the birth of agriculture with the development of early crops, the decline of hunter gatherer lifestyles and the start of the society we live in today (gluten intolerance sufferers probably think this is where it all started to go wrong). And all because we learnt to collect seed from promising looking grasses, and start planting in quantities we could harvest.

Tell us more about the plant identification courses. What are these all about and how people can get involved?

When we set up The Species Recovery Trust we knew that funding projects over a long term basis (all our work plans are 50 years long) was going to be a challenge, so we set about seeking ways to bring in modest sums of unrestricted funding over that period of time, for which running training courses was an obvious contender. This was combined with my passion for teaching plants, and then finding other people who shared this view. We’ve now been able to build up a team of some of the best tutors in the country, who combine their expert knowledge with running courses that are extremely fun and really help people get to grips with a range of subjects.

By automating the booking process (which works most of the time) we can also keep our prices extremely competitive, as well as offer discounted places for students and unemployed people who are desperate to get into the sector. On alternate years we offer one ‘golden ticket’ which enables one winner to attend 10 training courses for free, which will give people a huge helping hand in their conservation careers.

All the information on the courses can be found on the training courses page of The Species Recovery Trust website.

Can you tell us about any interesting projects you are involved with at the moment?

We have a great project running on Spiked Rampion at the moment, and after 6 years we now have the highest number of plants ever recorded, all due to a fantastic steering group of the good and great from Kew, Forestry Commission, Sussex Wildlife Trust, and East Sussex County Council, along with some very committed local volunteers. It’s been a lot of work but proved a great example of many organisations joining up with a single achievable aim of saving a really rather special plant from extinction.

This summer is going to see a network of data loggers placed around the New Forest as part of a project to re-discover the New Forest Cicada, that we’re working on with Buglife and Southampton University. There are real concerns about whether this species is already extinct, but as it spends most of its life underground and only emerges and sings for a short period it is a good contender for the UK’s most elusive species.

A Field Guide to Grasses, Sedges and Rushes is available from NHBS