The Flight Lines Project is a collaboration between the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and the Society of Wildlife Artists (SWLA). Using a unique combination of art, stories and science, this project aims to explore the lives of migrant birds and to highlight the challenges they face in a rapidly changing world.

In this interview with Flight Lines author, Mike Toms, we talk about the relationship between art and science, the importance of volunteer ornithologists and cultural differences in our attitudes to birds.

I’m curious about the perceived division between the arts and the sciences. While it’s true that many artists portray images of the natural world in their work, there are not many situations where artists and scientists are required to work together towards a common aim. Flight Lines is obviously a wonderful example of this – where did the idea for the project come from and what do you consider to be the most important thing that came out of it?

There is growing evidence that audiences exposed to science and conservation messages through the creative arts are more likely to show meaningful change in their understanding, which suggests that those of us working in research should seek now opportunities to communicate the impact of our work. Flight Lines was made possible by the generous legacy left by Penny Hollow and the kindness of her executors. Penny, a long-standing BTO member was a regular at the Society of Wildlife Artists (SWLA) exhibitions, a great supporter and a lay member of the SWLA. The bringing together of artists and scientists to raise the profile of our migrant birds was a fitting tribute to her interests and something that we had been looking do alongside our programme of research into migrant birds. Not only has the project enabled us to tell the stories of our summer visitors to new audiences but it has also helped to underline how art and science can work together to effect change.

Our knowledge of where our migrant birds disappear to each year has vastly increased with the development of ever smaller and more advanced tracking devices and locators. What do you think will be the next big technological advancement in the study of bird migration?

Our knowledge of where our migrant birds disappear to each year has vastly increased with the development of ever smaller and more advanced tracking devices and locators. What do you think will be the next big technological advancement in the study of bird migration?

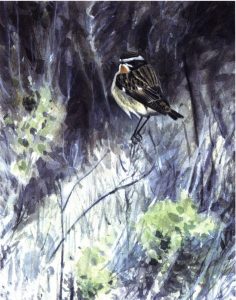

It is the arrival of smaller and smaller devices that has revolutionised our understanding of the movements of migrant birds. The level of information that can now be collected through the use of GPS-tags and satellite-tags means that we can identify the sites and habitats used by migrant birds throughout the year. In some cases, such as with those tags that communicate via the mobile phone or satellite network, the information collected can be presented to the public in near real time, greatly adding to wider engagement with the science that is being undertaken. For the smallest birds, the tags used have to be retrieved the following year in order to download the data. As miniaturisation continues, we will soon be able to track the movements of Swallows, House Martins, Whitethroats and other small migrants in near real time. That will be a significant advancement for our understanding.

In the UK I think it would be fair to say that we have an above average obsession with birds and their welfare. This is in stark contrast to many of the countries you discuss in the book, where birds are often viewed mainly as food or hunting trophies. What do you think is responsible for this difference in attitudes?

In the UK I think it would be fair to say that we have an above average obsession with birds and their welfare. This is in stark contrast to many of the countries you discuss in the book, where birds are often viewed mainly as food or hunting trophies. What do you think is responsible for this difference in attitudes?

It is incredibly important to recognise the cultural differences that exist between countries in terms of how birds are viewed. Many of these are deeply rooted and extend back through generations, each shaped by local beliefs and opportunities, by living conditions and by trade. The hunting of migrant birds in North Africa, for example, is shaped by at least three different drivers: some are hunted for food by people living in very poor communities; others are hunted because of cultural beliefs, and many are hunted because there is a sizeable market for such commodities within the Middle East. It is important that we recognise how attitudes towards birds differ across the globe so that we can deliver approaches to conservation that are sensitive and appropriate.

The subject of supplementary feeding is currently a hot topic with the recent publication of an article in Science showing how great tits’ beaks have changed size due to the use of garden feeders. However, the messages we receive about feeding our garden birds are very mixed. Do you think the amount of supplementary feeding that occurs in the UK is a good thing overall?

The subject of supplementary feeding is currently a hot topic with the recent publication of an article in Science showing how great tits’ beaks have changed size due to the use of garden feeders. However, the messages we receive about feeding our garden birds are very mixed. Do you think the amount of supplementary feeding that occurs in the UK is a good thing overall?

The provision of supplementary food is one of the most common deliberate interactions between people and wild birds, supporting a wild bird care industry within the UK worth an estimated £210 million each year. Despite the huge amount of supplementary food provided in gardens we know surprisingly little about its impacts, which is one of the reasons why the BTO has been funding research into this topic over many years. Supplementary feeding may increase the overwinter survival of small birds, shape the communities of birds living alongside us and alter migration patterns and behaviour. It may also change the dynamics of competition between species or aid the spread of new and emerging diseases. Before we can say whether or not it is a good thing we need to improve our understanding of the associated costs and benefits, and look at these in relation to other human-bird interactions, such as climate and habitat change.

Citizen science schemes are an incredibly powerful force in terms of obtaining large quantities of data and you frequently mention in your book how much of our knowledge about bird populations comes from the tireless efforts of volunteers. Do you think that being involved with a citizen science project is also empowering to the individual and can help to break down some of the boundaries between “professional” scientists and amateurs, making science and research more accessible to them?

Citizen science schemes are an incredibly powerful force in terms of obtaining large quantities of data and you frequently mention in your book how much of our knowledge about bird populations comes from the tireless efforts of volunteers. Do you think that being involved with a citizen science project is also empowering to the individual and can help to break down some of the boundaries between “professional” scientists and amateurs, making science and research more accessible to them?

The terms ‘professional’ and ‘amateur’ are often used incorrectly, suggesting that staff are professionals while volunteers are amateurs, when what is really meant is that staff get paid and volunteers don’t . Many volunteers are experts in their field, sometimes the expert, and the right approach to citizen science should recognise this. We know from various research studies that volunteers participate in citizen science for a whole host of different reasons, some linked to internal values – such as feeling good about yourself – and some to external – such as sharing expertise, contributing towards charitable objectives. A well run citizen science project should make the science being carried out more accessible to participants, enabling them to see how their contribution is being used to answer a particular research question and empowering them to recognise the impact that their involvement is facilitating.

Do you feel that your art is influenced by your love of birds and wildlife and, conversely, do you feel that your art affects your appreciation of the natural world?

Some of my writing – the prose and poetry – is influenced by the natural world and by the sense of place. This feeling for the natural world is equally evident when I am participating in BTO surveys, especially the Nest Record Scheme, where significant time is spent immersed in nature, watching birds and their behaviour in order to find and monitor nesting attempts.

Flight Lines is published by the British Trust for Ornithology and is available to buy from NHBS.