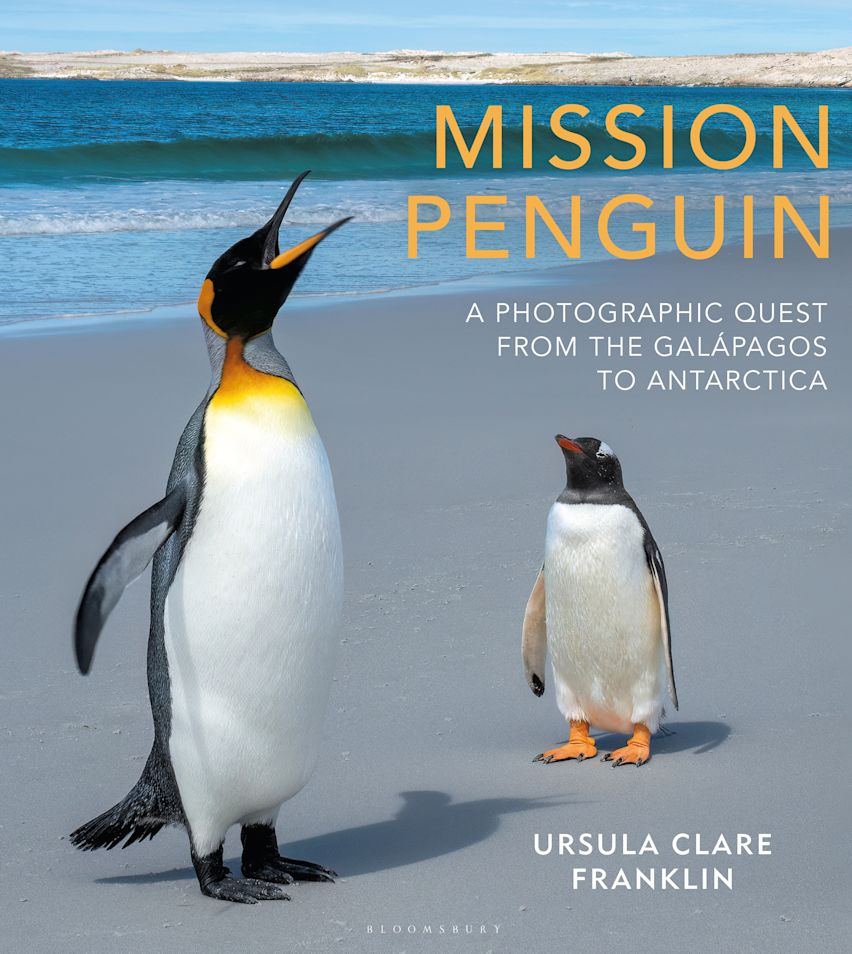

Following the loss of her husband, Ursula Franklin embarked on a mission to see and photograph every species of penguin in their natural habitat. In this breathtaking book, join Ursula on expeditions to some of the most remote places on earth, from the Falklands to Tristan da Cunha and Antipodes Islands, in search of these much-loved birds. Interspersed with stories from Ursula’s adventures, each chapter explores a different species of penguin, detailing their identifying features, the ever-increasing threats they’re facing, and the conservation efforts needed to ensure future generations can experience the wonder of these animals.

Following the loss of her husband, Ursula Franklin embarked on a mission to see and photograph every species of penguin in their natural habitat. In this breathtaking book, join Ursula on expeditions to some of the most remote places on earth, from the Falklands to Tristan da Cunha and Antipodes Islands, in search of these much-loved birds. Interspersed with stories from Ursula’s adventures, each chapter explores a different species of penguin, detailing their identifying features, the ever-increasing threats they’re facing, and the conservation efforts needed to ensure future generations can experience the wonder of these animals.

Ursula Franklin is a keen wildlife photographer who grew up in Yorkshire, and is now based in Somerset. She developed a keen interest in photography when she was a child and her wonderful husband supported her passion until his sudden death in 2012. As a way to process her grief and heal, alongside her husband’s constant encouragement for her to ‘do something with her photography’, Mission Penguin was born.

We recently had the opportunity to talk to Ursula about her expedition, how she thinks we can we work to protect these vital species in the future, her favourite memories throughout this journey and more.

Plus, enter our prize draw to be in with the chance of winning one of four exclusive Mission Penguin prints here.

Having travelled around the world and seen every species of penguin in every habitat, which species surprised you the most and why?

Like many people, I had always associated penguins with snow, so it was amazing to discover that some species breed in forests, others in the desert and one species even at the equator. The species that really surprised me, however, and for a totally different reason, was the Royal Penguin. This species breeds on Macquarie Island, and in the north of the island are the rusted remains of huge digestors which were once used to extract oil firstly from seals and then when they ran out, penguins. Millions of King and Royal Penguins were slaughtered leaving just a few thousand birds when the barbaric practice was finally stopped. Having suffered years of persecution by man, I marvelled at how trusting the birds were. As I sat on the beach, groups of Royal Penguins waddled up to me, inquisitively studying my boot laces, camera bag and equipment. They were so curious and seemed utterly fearless. It was hard to imagine humankind betraying such trust. Luckily, over the last 100 years, their numbers have steadily increased and in 2022 they were finally taken off the list of near-threatened species (IUCN red list). Hopefully they will continue to increase despite the human-induced climate change crisis.

You were lucky enough to witness the full, daily lifecycle of a number of penguin colonies by watching them from dawn until dusk, and I particularly loved the photographs of the Gentoo penguins on Saunders Beach at sunset. What does the typical day in the life of a penguin look like?

A day in the life of a penguin varies hugely depending on the time of year, especially during the breeding season, or when moulting. At other times of year, the birds spend their time foraging in the open ocean. During their annual moult, which usually lasts around 3 weeks, they are no longer waterproof so cannot go into the ocean to feed – instead they must stay on land living solely off their fat reserves. The breeding season is when they spend time on both land and sea. For most species, males and females share incubation of the egg/s and often take it in turns to go foraging to feed the hungry chick/s whilst the other parent stays to protect it/them. With some species, as the chicks get older, they are left in a crèche, or some stay in a burrow, allowing both parents to go to the ocean to collect food for their increasing appetites. The birds often leave at dawn when foraging, and the length of time they are away depends on how far they must swim to find food. For some species, warming ocean temperatures have shifted prey populations further from the colony leading to chick starvation and mass breeding failure. When the parents do return with food, some species engage their older chicks in long food chases before finally stopping to feed them. This is done to build up the strength of the chicks prior to fledging and is hilarious to watch. The adults then stay with their chicks at the colony overnight before the whole process starts again early the next morning.

You travelled around the world and have seen so many different places as a result of this project – what was your favourite memory and why?

This is such a hard question. I could say the very beginning of the mission on the Antarctic Peninsula with the sighting of my first penguin – this was a Chinstrap Penguin and has since become my favourite species, probably because the black strap under their chin makes it look as if they are smiling. Or I could go to the very end of the mission at Snow Hill Island with the Emperor Penguin colony, which was like being on the film set of the movie Happy feet and a very fitting and emotional accomplishment of Mission Penguin.

My favourite travel destination, however, is the Falkland Islands. With fewer than 4000 people, beautiful coastlines and over one million penguins of five species I’m sure you can understand why. My favourite island is Saunders Island and my favourite location there is ‘the neck’. The accommodation is very basic and although small can technically sleep 8 in 4 sets of narrow bunk beds. Incredibly, on my last visit, my friend Hazel and I were the only occupants – apart from the penguins of course! What a joy and privilege to be the only humans sharing their world and a memory that will stay with me forever.

Having witnessed first-hand the negative effects of both climate change and human activity on penguin colonies, and their respective habitats, how can we work to protect these vital species in the future?

Penguins are key indicator species for the health of our oceans and the effects of global warming. Although there are no penguins naturally occurring in the Northern Hemisphere, our everyday actions here will ultimately filter down to the Southern Hemisphere and affect these animals.

One of the most threatened penguins is the African Penguin, and research suggests that this species could become extinct in the wild by 2035 unless we act now. Whilst we have little influence on African governments regarding marine ‘no-take’ zones, limiting coastal development, (oil refineries etc) can still help. For example, all of us can reduce our use of plastics (especially single use), and switch to renewable energy sources.

For more direct and immediate help we can also sponsor penguin nest boxes. African Penguins naturally lay their eggs in burrows which are dug out of layers of guano (bird poo!) laid down over hundreds of years. In the 1800’s most of this guano was collected and shipped to the UK to be used as fertiliser. As a result, there has been a 99% decline in the population over the last 100 years. As land temperatures continue to rise, penguins now nesting out in the open air are either dying from hyperthermia or abandoning their nests to save themselves, leading to mass breeding failure. Carefully researched and crafted nest-boxes that replicate the conditions of a guano burrow are proving effective – to help visit the Saving Penguins website.

Photographing every species of penguin is no small feat, especially alongside a full-time job! What were some of the biggest challenges you faced and what did you learn along the way?

When I announced to a friend that I was going to photograph every species of penguin in their natural habitat, I had no idea how many species there were or where they could be found. My research took me to places that I had never even heard of and to say many of them were ‘off the main tourist route’ would be an understatement! Simply getting to the required and often incredibly remote locations was definitely the first challenge. Many of these are also found in the roughest oceans in the world, and I suffer dreadfully from sea sickness. Needless to say, I was often very unwell but even that could not detract from the awe and wonder of these amazing expeditions. Once at the location, sometimes I only managed fleeting glimpses of just a few penguins of that species so not many photographs, but I appreciate how very lucky I was to actually see and photograph every penguin species on the first attempt.

The weather also presented significant challenges (especially the wind), and trying to photograph from a Zodiac (Rigid Inflatable Boat) while being tossed around in large swells was at times nigh on impossible. I also needed to keep my equipment warm in Antarctica and dry in the humidity of the Galápagos. Sunshine, although lovely in itself, also made photographing black and white birds more difficult than normal in terms of achieving correct exposure. I certainly learned to tolerate imperfections but also became a better photographer along the way. I also witnessed firsthand how tenacious and resilient penguins are – characteristics that we can all learn from.

Mission Penguin came to fruition as a result of loss and grief, and throughout the book I found it heartwarming to read about the healing effects of your expeditions. How important do you think nature is in healing from grief, and what are the benefits of spending time exploring the natural world?

Nature is indeed an incredible healer. I have lovely memories of my mother taking us out on nature walks when we were young as we didn’t have much money, and nature was all around us and free! I think from that age I learned to appreciate the wonder of nature and delight in simple things, so when grief struck, getting out in nature and reconnecting with life and beauty was essential to my healing. Nature stimulates all of our senses which certainly helped me to feel fully alive even in the context of death. What inescapable joy to hear the birds singing, see the dappled light in a woodland glade, smell the flowers, taste the salty sea air, and hug a tree! Being immersed in the natural world really helps to put things into perspective and to feel part of something much greater than ourselves. In nature I feel fully grounded which gives me an inner peace and the strength to keep going, one step at a time.

What’s taking up your time at the moment? Are you working on any other projects or planning any upcoming expeditions that we can hear about?

Following the completion of Mission Penguin I have spent more time delighting in the natural world on my doorstep. In the last couple of years, I have finally taken up gardening, which my husband would have found hysterical having tried to persuade me all our married life! My focus however is gardening with wildlife in mind, and I think we would have had very different definitions of a ‘weed’! I am also rewilding one large area and quickly learned the hard way that rewilding is not the same as letting things go wild! I am still taking lots of nature photographs and readers can see more of my images here.

As well as writing the book, I started giving talks on Mission Penguin to local groups and this quickly expanded to other topics as they keep inviting me back for more. I now have about 6 talks in my repertoire so that is keeping me busy as well as continuing with my singing – another fabulous activity for wellbeing.

I am a firm believer in making the most of every moment. We only have one life, so live it well. Fill it with friends, joy, laughter – and of course, penguins.

Enter our competition to be in with the chance of winning one of four exclusive Mission Penguin prints signed by author Ursula Franklin here – good luck!

Mission Penguin is available from our online bookstore here.