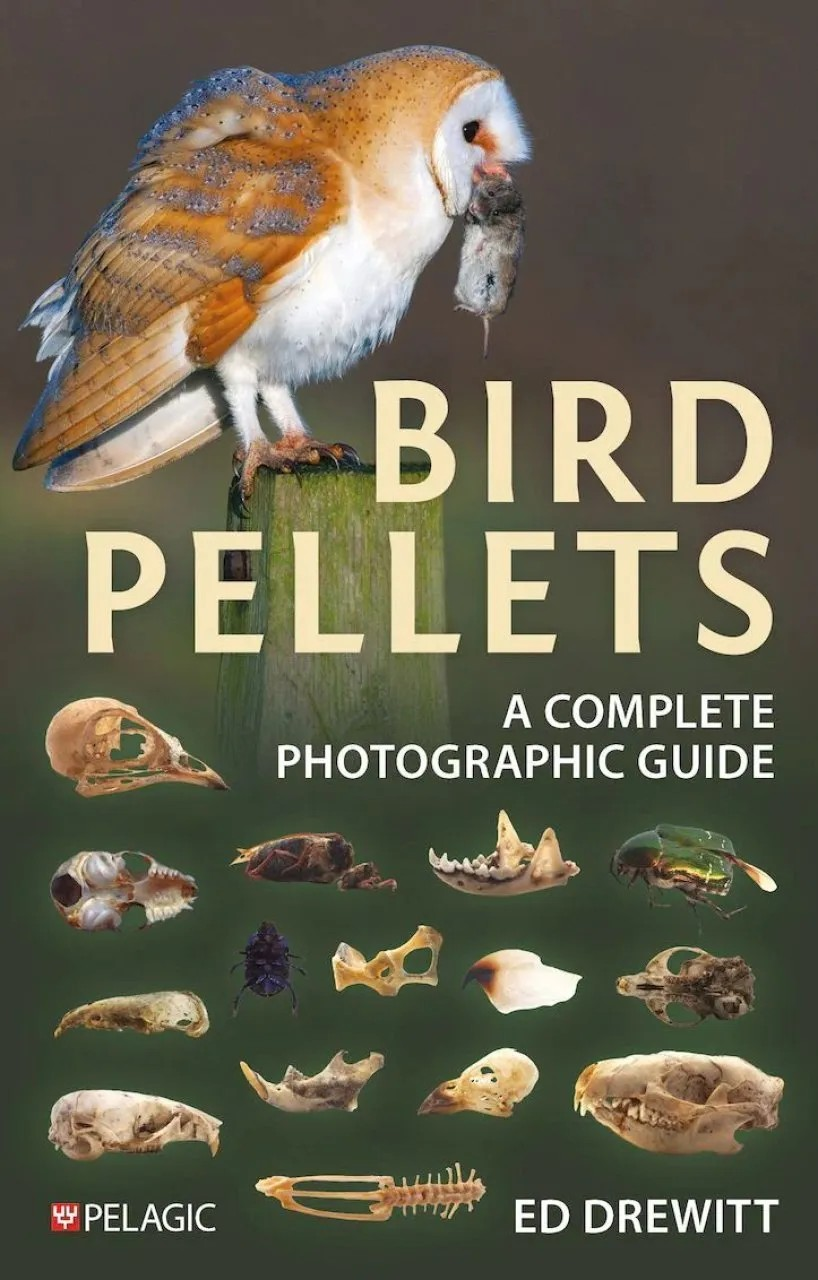

This is the first comprehensive guide to bird pellets showcasing a wide range of pellets produced by different species, including owls, hawks, waders and various garden birds. Author Ed Drewitt offers a methodical introduction to pellets, outlining what they are, how they’re formed, dissection methods, analysis and common findings, accompanied by an array of detailed illustrations and photographs. Bird Pellets provides a closer look at those produced by each species in turn and outlines how to identify the remains of small mammals, which can be an important tool for discovering what a bird feeds on, understanding dietary change over time and other aspects, making this an invaluable resource in ecology.

This is the first comprehensive guide to bird pellets showcasing a wide range of pellets produced by different species, including owls, hawks, waders and various garden birds. Author Ed Drewitt offers a methodical introduction to pellets, outlining what they are, how they’re formed, dissection methods, analysis and common findings, accompanied by an array of detailed illustrations and photographs. Bird Pellets provides a closer look at those produced by each species in turn and outlines how to identify the remains of small mammals, which can be an important tool for discovering what a bird feeds on, understanding dietary change over time and other aspects, making this an invaluable resource in ecology.

Ed Drewitt is a professional naturalist, wildlife detective and broadcaster for the BBC who specialises in the study of birds and marine mammals. He studied Zoology at the University of Bristol, before working at Bristol’s Museums, Galleries and Archives for numerous years. He is now a freelance learning consultant who runs bird identification courses, provides wildlife commentaries on excursions, writes for wildlife magazines and is involved in bird ringing studies. Ed is also the lead researcher in a study focusing on the diet of urban-dwelling peregrines in the UK and author of Urban Peregrines.

Ed Drewitt is a professional naturalist, wildlife detective and broadcaster for the BBC who specialises in the study of birds and marine mammals. He studied Zoology at the University of Bristol, before working at Bristol’s Museums, Galleries and Archives for numerous years. He is now a freelance learning consultant who runs bird identification courses, provides wildlife commentaries on excursions, writes for wildlife magazines and is involved in bird ringing studies. Ed is also the lead researcher in a study focusing on the diet of urban-dwelling peregrines in the UK and author of Urban Peregrines.

Firstly, can you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came to write a book about bird pellets?

I have been interested in wildlife, particularly birds, since I was six or seven. Back then I would love collecting feathers and skulls, and bird pellets. I remember being excited at finding a Sparrowhawk plucking–perch in the woods where I lived in Surrey and finding small pellets – packed full of small feathers – from the hawk. Much of my career has involved developing and delivering learning workshops and resources for school-aged students and my public engagement work involves communicating science in plain English. Therefore, I am well versed in writing a book that appeals to families, schools and researchers alike. For several years I worked part-time in the teaching laboratory for the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol. Each spring I would help oversee students dissecting several hundred Barn Owl pellets; I also arranged for a live owl and Kestrel to come in, to bring the practical ‘alive’. I have also been studying what urban-dwelling Peregrines eat (and am author of Urban Peregrines and Raptor Prey Remains) over the past 26 years. Therefore, I was in a brilliant and timely position to tap into my own pellet and bone collection, and source more material from others across the country and beyond, to write the ultimate bird pellet book!

Most people are aware that owls and raptors produce pellets, but are there any pellet-producing species that we’d be more surprised to hear about?

Absolutely – any bird that eats something that is indigestible and unable to pass through the intestines and out the other end, will produce a pellet. People are always surprised when I explain that even Robins and Blackbirds produce pellets, often made up of bits of woodlice and beetles. Interestingly though, two raptors, that you might expect to produce pellets do not: the Osprey and the Honey Buzzard. Both eat foods that either are digested or picked at, meaning harder parts, such as bones, are not swallowed.

I was interested to read in your introduction to the book that pellets can be used to study what birds were eating thousands or even millions of years ago. Are bird pellets generally well represented in the fossil record?

The brilliant thing about pellets is that, while their general structure may break down, their contents, for example, mammal and bird skulls, may accumulate in one area, even if they get buried over time. While some bits will slowly decay or move over time, others may remain in situ and intact. Palaeontologists and archaeologists often study how animals decay; it is known as taphonomy. It can also be applied to pellets. While complex, researchers can work out which species has produced a pellet and what happens to its contents with time. In turn, researchers can determine previous assemblages of prey species, such as small mammals, and how these have changed over time depending on environmental and ecological conditions. This type of study can also work out which species are more (or less) likely to be found in such accumulations and therefore how the fossil record may be biased towards particular prey species.

Many of us will be familiar with the technique of using the visual observation of bones and other remains in pellets to study what was in a bird’s diet. But are there more advanced laboratory methods that are now being used to study them in more detail?

Yes, although I don’t think they are quite as fun or smelly! In essence, taking swabs from pellets can reveal the DNA of what has been eaten, including things that may not otherwise be detectable, although some of these items may have been eaten by the prey itself, if the DNA is intact enough. It can work the other way though; well digested food remains may mean the DNA of prey is undetectable or so degraded it cannot be assigned to a species or taxa, while traditional visual techniques may be able to confirm its identity.

Can pellets be useful for studying the presence of pollutants in the environment, such as plastics and microplastics?

Absolutely, and this is not a new thing, although it is now more topical in the media. Some seabirds, such as terns and gulls, have been producing pellets with polystyrene particles going back to the 1970s. However, now we have a better idea of just how much plastic is in our environment, we are now looking for it more in the stomachs and pellets of birds. Dippers are a very good example. Small invertebrates, such as stonefly larvae, ingest microplastics. They are then eaten by Dippers and the plastics accumulate in the pellets they regurgitate. Of course, the cumulative health effects that ingesting plastic has on birds such as Dippers is difficult to ascertain. Even Barn Owl pellets may contain microplastics, ingested from the stomachs of small mammals they are eating.

What is the most surprising or unusual thing you have found in a bird pellet to date?

Gull pellets are often the most interesting, mostly because of the litter they contain, from plastic particles and bags to condoms! On a more natural note, the most spectacular pellet I have found was on the Flannan Isles, a remote island west of the Isle of Lewis, Scotland. The pellet was from a Great Skua, and it contained a whole Leach’s Petrel, which also live on the island. The petrel had gone down into the stomach where it had been digested. It was then regurgitated as a pellet, pretty much as a whole bird including intact wings, just minus any flesh! Skuas and Great Black-backed Gulls will also do the same thing with young rabbits and Puffins. Pellets can also be useful for finding the rings of wild birds and discovering that a bird has eaten another bird with an interesting origin of ringing, such as Norway or Russia!

Finally, what’s keeping you occupied this summer, and do you have further books in the pipeline that we can look forward to?

During the summer I am busy taking people out to see wildlife, especially in the Forest of Dean, where I live. I especially love birdsong and helping others to hear it. I am also working with the RSPB on the Gwent Levels, doing some training courses on identifying saltmarsh plants and wildlife. My wife, Liz, and I have two children, aged four and seven, so we will also be busy keeping them occupied! They love the outdoors and enjoy seeing wildlife just like we do. I have some papers in the pipeline as I am halfway through a part-time PhD at the University of Bristol. My 26-year study of the diet of urban-dwelling peregrines has given me plenty of data to analyse and write into chapters for my PhD.

Bird Pellets will be published by Pelagic Publishing and is available to pre-order from our online bookstore.