Throughout her life, Elizabeth Gould’s work was appreciated mostly through her husbands projects documenting the birds of the world, including John Gould’s Exotic Birds, and she was therefore often not recognised under her own name. Following her tragic death at the age of 37, her artistic talents were nearly forgotten, and her name was completely unfamiliar in the art world.

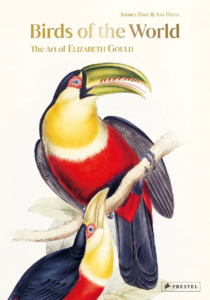

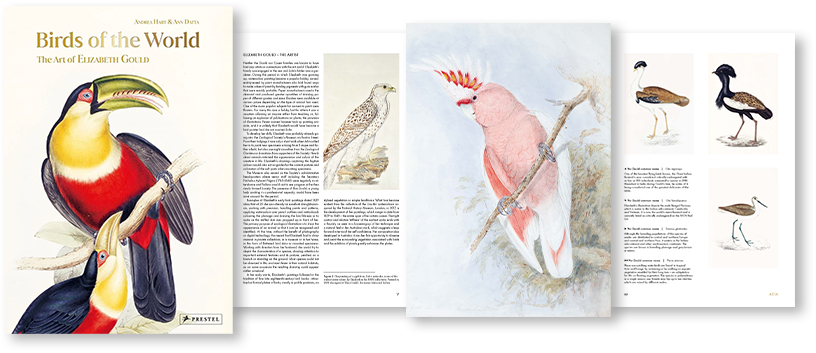

Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould is an incredible, one of a kind volume brought to you by Andrea Hart and Ann Datta, offering a remarkable tribute to Elizabeth’s artwork, reputation and skill. Containing over 200 beautifully detailed and scientifically precise illustrations depicting birds from 19th-century Europe, South America, Central America, Africa, Asia, and Australia, as well as previously unpublished artworks and an introduction to Gould’s life and achievements, this book is a lasting legacy for one of the greatest bird painters in history.

Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould is an incredible, one of a kind volume brought to you by Andrea Hart and Ann Datta, offering a remarkable tribute to Elizabeth’s artwork, reputation and skill. Containing over 200 beautifully detailed and scientifically precise illustrations depicting birds from 19th-century Europe, South America, Central America, Africa, Asia, and Australia, as well as previously unpublished artworks and an introduction to Gould’s life and achievements, this book is a lasting legacy for one of the greatest bird painters in history.

The authors kindly took the time to answer our questions about the inspiration and research behind the book – read our Q&A below.

Could you tell us a little about how you first began studying Elizabeth Gould’s work and the drivers behind embarking on this book project?

The Natural History Museum was initially approached by the publisher, Prestel, early last year asking if we might consider working with them on a book on Elizabeth Gould. As Andrea had already published a book on the women artists represented in the Museum’s collections and Ann has published a significant work on the correspondence of John Gould, this felt like a wonderful opportunity to bring the spotlight to Elizabeth and highlight her story and the incredible artist she was.

How did you gather the work for this collection? Did you have access to some of Elizabeth’s original plates?

The Museum’s Library and Archives has an incredible collection of books, manuscripts and artworks and is particularly strong and comprehensive in taxonomic works on natural history. Our rare books collection therefore has sets of all the Gould’s published works, including those published following Elizabeth’s untimely death. While we held some examples of Elizabeth’s original works already, notably the ones she completed for William Jardine, we were incredibly fortunate to have been permanently allocated an album of her and John’s original works through the Acceptance in Lieu scheme of Arts Council England. This publication therefore gave us a wonderful opportunity to share some of these historically significant original drawings with a wider audience, and to further appreciate her artistic talent.

The Museum’s Library and Archives has an incredible collection of books, manuscripts and artworks and is particularly strong and comprehensive in taxonomic works on natural history. Our rare books collection therefore has sets of all the Gould’s published works, including those published following Elizabeth’s untimely death. While we held some examples of Elizabeth’s original works already, notably the ones she completed for William Jardine, we were incredibly fortunate to have been permanently allocated an album of her and John’s original works through the Acceptance in Lieu scheme of Arts Council England. This publication therefore gave us a wonderful opportunity to share some of these historically significant original drawings with a wider audience, and to further appreciate her artistic talent.

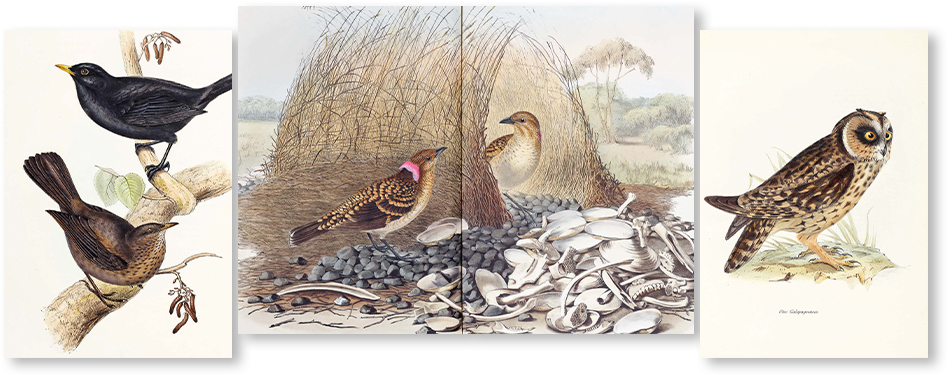

Do you have some favourite images among the plates Elizabeth made?

This is a really tricky question as most of the illustrations that we chose are most of our favourites! Ann specifically likes the bowerbirds, the Narina Trogon, the quetzal and the Australian wren and Andrea became quite fond of the toucans (but also had to include a magpie).

It’s clear from the biography of Elizabeth Gould in your book that she was incredibly industrious and hard-working, and that she experienced a great deal in her short life during a remarkable period in history. Do you get a sense that Elizabeth Gould paved the way for more women to work as artists in this field?

There is no evidence that Elizabeth Gould was influential in inspiring other women to become bird artists due, probably, to her short life. After her death in 1841, Gould’s folios were continued seamlessly by the draughtsmanship of Elizabeth’s successor, Henry Constantine Richter. Only those who knew the Goulds intimately would have been aware of her early contribution to the success of the folios. John Gould went on producing bird books for another 40 years, their contemporaries died and few questioned who was the ‘E’ in the ‘J & E Gould’ plate credits in the earlier books.

Also, although Elizabeth may have been a promising artist as a young woman, it was not an easy career path to succeed in, and she chose to become a governess with more security. Elizabeth probably would not have become a bird artist had she not married John. John had the scientific knowledge to identify the birds in the preserved, dried skins and provided sketches to guide Elizabeth’s meticulous watercolours. They were truly an equal partnership.

During Elizabeth’s lifetime, plants were a much more popular subject for women artists to take up than animal subjects, and a few women who were Elizabeth’s contemporaries were successful in this line. But in general, there were few opportunities for women to follow a successful career in art.

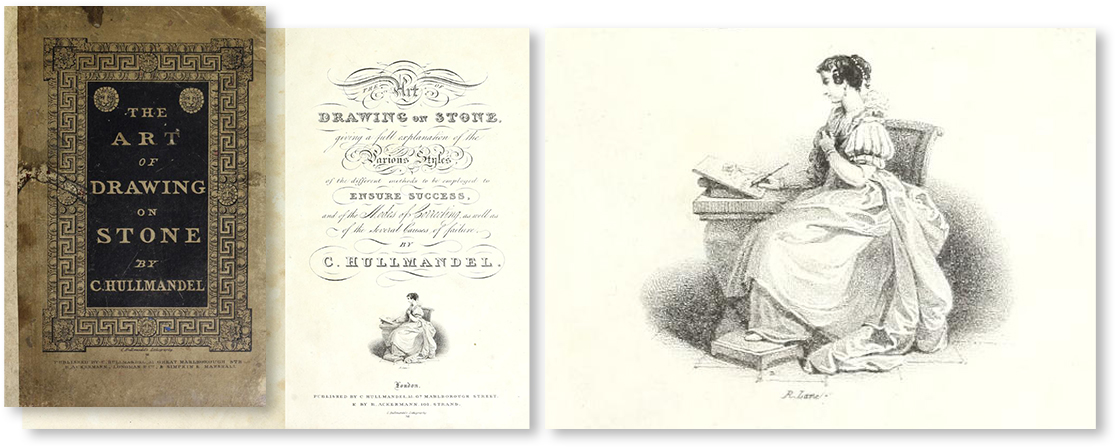

I found it fascinating that many of Elizabeth’s plates are made using a lithographic process. I wonder if you could elaborate a little on that process and the time it would have taken to produce an individual plate?

All Elizabeth Gould’s published plates for John Gould were made by the lithographic process. Lithography seems a very strange process but in the 19th century it was adopted by hundreds of aspiring artists of all subjects – history paintings, genre scenes, topography and natural history. The lithographic method dominated print and book plate production in the 19th century replacing the more expensive engraving process. By using lithography, artists could make monochrome prints of their original paintings which they could sell to the public – the rising middle classes who wanted affordable art to hang in their homes. Learning and doing the lithography themselves had two advantages for the artists: total control of the print-making process and avoiding the expense of hiring a lithographer. Those artists who mastered the technique, such as George Scharf, had no need to go to the extra expense of adding colour as they could create great delicacy of tones and lines in landscapes and street scenes etc, just by adding shading and stippling effects on the stone. Some of the most acclaimed natural history artists such as Edward Lear (contemporary of Elizabeth) and Joseph Wolf learned lithography. Lithography was especially well-suited to reproducing bird plumages, from soft down to large feathers.

The process of lithography consists of drawing or painting with greasy crayons and inks on fine-grained limestone blocks. At the lithographic printer, where the stone would be taken after the artist had finished, the stone would be moistened with water. The parts not covered by the crayon would become wet while the others where the greasy drawing was made would repel the water and remain dry. In a special lithographic press the printer would rub an oily ink with a roller over the stone. The oily ink would adhere only to the drawing but be repelled by the wet parts of the stone. After a sheet of paper was pressed against the inked drawing an exact copy of the original on the stone would be transferred to the paper but in reverse. The process would be repeated until the requisite number of prints was taken after which the stones would be cleaned for the next person, although the stone with its original drawing could be preserved for several years. The stones were very heavy. A Gould plate measured 22 × 16 inches. A stone measuring 18 × 22 inches would be about 3 inches thick and weigh 100 pounds.

The Art of Drawing on Stone, courtesy of archive.org

The Art of Drawing on Stone, courtesy of archive.org

The lithographic printer Charles Hullmandel was responsible for all Elizabeth’s plates. His book, The art of drawing on stone (1824), has a vignette on the titlepage of a woman working on a stone. The first prints that came off his printing press – proof plates before lettering – were sent to Gould to approve. Then they went back to Hullmandel for him to add lettering to the stone according to Gould’s instruction (title = bird name, credits to the names of the artists, lithographer and printer). The proof plate after lettering, still a monochrome print, would go back to Gould again for her to colour to match her original watercolour. This artist’s colour proof would go to Gabriel Bayfield, the proprietor of a firm of colourists used for all Elizabeth’s plates, for his employees to copy the proof print on the requisite number of copies of each plate that Gould ordered.

Using this complicated and time-consuming process, each title took several years to complete. The books were sold by subscription (maximum number of subscribers often 250) who received parts, perhaps four times a year, and each part might contain 20 hand-coloured plates. The time taken to produce a lithograph would depend on the competence and confidence of the lithographer, and the complexity of the subject.

Elizabeth’s life contained many intense hardships. Aside from her incredible artworks, is there much record of her personal life and experience, such as in letters and diaries?

Very little extant information exists about Elizabeth with only about 15 letters dating between 1838 and 1840 surviving, all of which are now preserved in the Mitchell Library in Sydney, Australia. They were written by Elizabeth to her mother and cousin who had moved into her house in London to look after the children while Elizabeth and John were in Australia. The letters record some details of their visit including the people she met, especially Sir John and Lady Franklin, who accommodated them for nearly 12 months in Tasmania. Other topics include some of the problems faced by European settlers, e.g. acquiring servants, schooling, and the adverse climate, John’s collecting trips and his helpful Aboriginal guides, and making plant drawings. She writes proudly about her new son Franklin, born in Tasmania in Government House, and regularly enquires about the health of her mother and children. She does, however, reveal profound sadness at being away from her three young children in London.

In addition, there is one earlier letter written by Elizabeth in 1827 to her mother when she was working as a governess in London before her marriage. Only a fragment of a diary written by Elizabeth over the few days from 21st August to 30th September 1839 is known. It was written after she had left Tasmania and travelled to New South Wales to stay with her brother Stephen Coxen. In it she describes seeing several unusual birds.

From other sources it is possible to glean a few snippets about John and Elizabeth’s life in London. For example, she travelled with John to visit museums in Europe, and she probably accompanied him on some visits to Sir William Jardine’s estate. In a letter to Stephen, John Gould wrote in May 1841 that all the family had gone to stay in Egham for four months (Egham was then a village in the country).

In what ways does the industry of art for scientific publications differ today? Are there any similarities to the time in which Elizabeth was active?

Elizabeth Gould’s bird drawings served the scientific community. Accuracy of posture, colours and pattern of plumage and external anatomy were particularly important, alongside the impact of an attractive image, all of which are still required for taxonomic identification today. This could be achieved by painting the figure on a branch or on the ground according to its natural habits, often in a profile position. For Elizabeth, we believe, she would have started with a pencil outline, following the sketch that John would have made to assist her assemble a life-like figure from a dried bird skin. Elizabeth’s first meticulous drawings were rather conventional figures of very static birds – a style which persisted for many years until it was broken by John James Audubon in the early 19th century. Audubon spent many years in the field in North America and was the first to successfully paint the birds in their authentic natural habitat. Influenced by Lear and Audubon, Elizabeth would gradually develop her technique to produce more lively birds reaching a pinnacle in the Birds of Australia with the inclusion of appropriate flora and landscapes.

Today, an aspiring artist might attend art school before specialising in natural history art. Those who progress onto becoming wildlife artists would still observe their subjects in the wild and have additional equipment and technology to assist them, including binoculars and digital cameras to record and perfect their art. The detail required remains the same in terms of studying the subject’s internal and external anatomy and showing in their illustrations the required detail to be able to determine differences between species.

Bird art, however, includes many different styles and techniques which can change according to the artist’s preferences or the client’s requirements. There is, for example, a particular style used in field guides to compare large numbers of species on a page. Bird monographs, on the other hand, might just focus on a particular family and devote a whole page to an image of just one species showing male, female and juveniles, and so there is endless variety depending on the nature of the publication. Some bird artists, such as John Busby, also have a uniquely ‘casual’ style that is perfectly capable of depicting birds accurately and recognisably, but is very different from that of a more traditional modern bird artist such as the brilliant Robert Gillmor, who sadly passed last year. Those that illustrate for scientific purposes would also, just like Elizabeth, need recourse to examining bird skins or taxidermy in museum collections at some stage in their work.

Digital photography has certainly made images of birds and the natural world more widely available for guides and species identification, but there is still definitely a demand for artists to illustrate new species and produce illustrations and detail that is not possible to achieve with a camera.

Do you have plans for any future projects or publications that you’d like to tell us about?

There are so many other collections and artworks held by the Natural History Museum that would be amazing to research and publish on. For Ann, who did publish a significant volume on the correspondence of John Gould, she has some additional research papers to complete and, if time permits, would like to publish a biography of Thomas Hardwicke, who was an army officer and naturalist in India. Andrea would like to work on the botanical artist Worthington George Smith and the natural history artist Denys Ovenden in addition to developing a new temporary exhibition on artworks in the Richard Owen collection at the Museum, for display in the Museum’s Images of Nature Gallery in 2024.

Birds of the World: The Art of Elizabeth Gould was published by Prestel in September 2023 and is available from NHBS – Wildlife, Ecology & Conservation