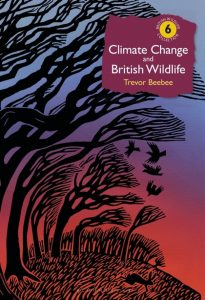

Climate Change and British Wildlife is the sixth installment of the popular British Wildlife Collection. In this timely text, Trevor Beebee takes advantage of our long history of wildlife monitoring to examine the effects that climate change has played so far on British species and their ecosystems. He also considers what the future may hold for them in a constantly warming environment.

Climate Change and British Wildlife is the sixth installment of the popular British Wildlife Collection. In this timely text, Trevor Beebee takes advantage of our long history of wildlife monitoring to examine the effects that climate change has played so far on British species and their ecosystems. He also considers what the future may hold for them in a constantly warming environment.

Trevor Beebee is Emeritus Professor of Evolution, Behaviour and Environment at the University of Sussex, Trustee of the Herpetological Conservation and Amphibian Conservation Research Trusts and President of the British Herpetological Society. He is also author of the Amphibians and Reptiles Naturalists’ Handbook and co-author of the Amphibian Habitat Management Handbook.

Last week, Trevor visited NHBS to sign copies of Climate Change and British Wildlife (signed copies are exclusively available from NHBS). We also took the opportunity to chat him about the background behind the book, his thoughts on conservation and his hopes for the future of British wildlife. Read the full conversation below.

![]()

Where did the impetus and inspiration for this book come from? Is it a subject that you have been wanting to write about for some time?

Where did the impetus and inspiration for this book come from? Is it a subject that you have been wanting to write about for some time?

It started in the garden some 40 years ago. For me, first arrivals of newts in the ponds were a welcome indicator that spring was on the way and I logged the dates year on year. It gradually dawned on me that the differences were not random but that arrivals were becoming increasingly early. Climate change seemed the obvious cause, and as evidence accumulated from so many diverse studies, it seemed like a good subject to write about.

The research required to cover so many taxonomic groups so comprehensively must have been immense. How long did you work on this book, including research, writing and editing?

The book took about a year to write. Electronic access to scientific journals made the research much easier and quicker than it would have been 20 years ago. Editing also took quite a while, greatly assisted by the perceptive advice of Katy Roper (my Bloomsbury editor).

The book covers plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, fungi, lichens and microbes as well as communities and individual ecosystems. Are there any of these that you feel are particularly at risk? Or conversely, are there any that you feel are more robust and are likely to better weather the effects of continued climate change?

The book covers plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, fungi, lichens and microbes as well as communities and individual ecosystems. Are there any of these that you feel are particularly at risk? Or conversely, are there any that you feel are more robust and are likely to better weather the effects of continued climate change?

It became evident as I researched that cold-adapted species including Arctic-alpine plants and fish such as the Vendace are in trouble, and that worrying trend is likely to generate declines or even extinctions in the coming decades. The ecology of the North Sea is also undergoing dramatic changes, some of which have precipitated seabird declines, especially of species such as Kittiwakes that rely heavily on sand eels. At the other extreme, mature woodland seems relatively resilient to climate change.

We have a rich history of wildlife monitoring and recording in the UK, much of which is undertaken by volunteers. Why do you think this is?

I believe that the media can take much of the credit for stimulating these activities. The end of the second world war was followed by the publication of a plethora of natural history books, from the I-Spy series (I still have a copy of ‘Ponds and Streams’), through the Observer series to the flagship New Naturalists. Then came television, with pioneers such as Peter Scott and David Attenborough in the 1950s. We’ve never looked back, with Springwatch today regularly attracting two million or more viewers. Brilliant!

Do you think that a thorough understanding of long-term monitoring and datasets can and should inform our decisions about where to focus conservation efforts?

Do you think that a thorough understanding of long-term monitoring and datasets can and should inform our decisions about where to focus conservation efforts?

Yes indeed, and fortunately such datasets are steadily increasing. The recent State of Nature reports have relied heavily on them, and they provide solid evidence that decision-makers can hardly ignore. One proviso though. For some species, especially rare ones, it is still difficult to obtain the necessary information. It would be a great mistake to ignore the plight of plants or animals clearly in difficulty simply because we don’t have robust monitoring data.

How did you feel after writing this book? Are you optimistic or despondent about the future for British wildlife?

Relieved! Sadly, though, not at all optimistic. There are some well-publicised success stories, such as the resurgence of several raptors, but more than fifty percent of Britain’s wildlife species are in continuous decline and there’s no sign of an end to that. Climate change is a problem for some, but it’s not the main one. Postwar agricultural intensification is the major villain, and it carries on regardless.

What single policy change would you like to see to alter the future of conservation in the UK?

What single policy change would you like to see to alter the future of conservation in the UK?

A serious commitment to change farming practices into ones that sustain our rich wildlife heritage. Research shows that this is possible without dramatic impacts on food production, despite the claims of the agrochemical industry. With a human population the size of that in the UK it will never be possible to provide enough food without imports and it’s about time that was accepted by farmers and politicians alike.

Finally, what’s next for you? Do you have another book in the pipeline?

The book I would like to write is one on the impact of overpopulation on British wildlife. It’s a sensitive subject but one clearly recognised by naturalists of the calibre of David Attenborough, Jane Goodall and Chris Packham, among others. The most serious issues, including intensive farming practices, relate directly to the number of people dependent on them.

![]()

Climate Change and British Wildlife is published by British Wildlife Publishing and is available from NHBS.

Signed copies of the book are available, while stocks last.

As one of the many unrecognized naturalists in this land I am party to the view of the impact of overpopulation on the natural world. And not only in the UK, but globally too. It’s a massive global problem that needs to be addressed!