Snorkelling is a great summer pastime and a brilliant way to experience many amazing species that inhabit our oceans. The inshore coastal environment is incredibly diverse and full of life, so there’s a chance you might see something different every time you snorkel! Depending on when and where you swim, you may even be able to see some creatures you recognise from rock pooling and learn how they behave when the tide is in.

Planning a trip

When planning a snorkelling trip, there are several important factors to consider. Firstly, it is important to familiarise yourself with the area you plan to snorkel in. To ensure your safety, make sure that there is constant, safe access to and from the sea, and that the water is clean enough to swim in. An understanding of potentially harmful species you might come across is also important. For instance, blue-green algae (which is actually a type of bacteria) can lead to illnesses in humans, and others, such as the Portuguese man-of-war (Physalia physalis), have very painful stings that could ruin your trip.

A big factor to take into account is the weather. Rain, wind and cold weather can all impact the quality of your snorkelling trip. From reducing visibility to causing dangerous conditions, the weather should always be taken seriously. Plan to snorkel on a warm, clear, calm day and make sure to continuously monitor the weather during your swim. Be careful not to swim at midday on a hot day either, if you are particularly sensitive to the sun.

Checking the water temperature is important, as it allows you to plan what you’ll need to wear and how long you should be in the water. You should aim to limit your exposure to colder water as it can lead to cold water shock and hypothermia.

Finally, the tide. It is best to swim as close to high tide or low tide as you can. Swimming in a changing tide can be tiring and can reduce the clarity of the water. High tide often offers the clearest water and allows snorkelling access to areas previously too shallow to swim in. It can also be safer in some areas: the increased volume of water could allow for greater space between you and any sharp rocks or reefs on the sea bed. This does mean that it may be too deep in other areas to clearly see the seafloor, so you might have to repeatedly dive down. Also, after high tide, the tide will begin to go out. This can be dangerous for swimmers, especially for those in areas with strong tidal currents, as you can be dragged further out to sea.

At low tide, you can snorkel further offshore, meaning you may see more species. However, certain areas closer to shore may be too shallow for safe snorkelling. The current will be in-bound after low tide, so you won’t be pulled out to sea, but you may be pushed into dangerous inshore areas. It is best to research the currents and coastal geography of the area before beginning your trip!

Check out our collection of tide times guides, as well as a few of our snorkelling guides.

Equipment and method

There are several key pieces of equipment needed for snorkelling and a few extras that can be useful. A snorkel and mask are obvious, but a pair of fins can help you swim for longer without tiring. They can also be helpful in stronger or unexpected currents. A wetsuit or rash vest is advisable for colder water temperatures, as are wetsuit shoes, gloves, and hats to help to keep you warm and protected in the water. A life jacket is a vital piece of gear to keep you afloat if you find yourself in danger or too tired to keep swimming.

Other equipment that you may want to bring are an underwater camera or a waterproof case for a phone. Dive slates or waterproof notebooks will help you keep track of everything you have seen.

To minimise disturbance while snorkelling, keep your distance from any animal you see and make sure not to step on or touch anything on the sea bed, as this habitat can be fragile. When diving down, be careful how you swim and return to the surface; kicking too hard can disturb any sediment below, reducing water clarity. This isn’t great for you as it can limit what you’ll be able to see, but it can also impact marine life, particularly corals and seaweed, as it reduces the amount of light that reaches them.

What could you see?

Spider Crab (Maja squinado)

Velvet Swimming Crab (Necora puber)

Common Lobster (Homarus gammarus)

Candy Striped Flatworm (Prostheceraeus vittatus)

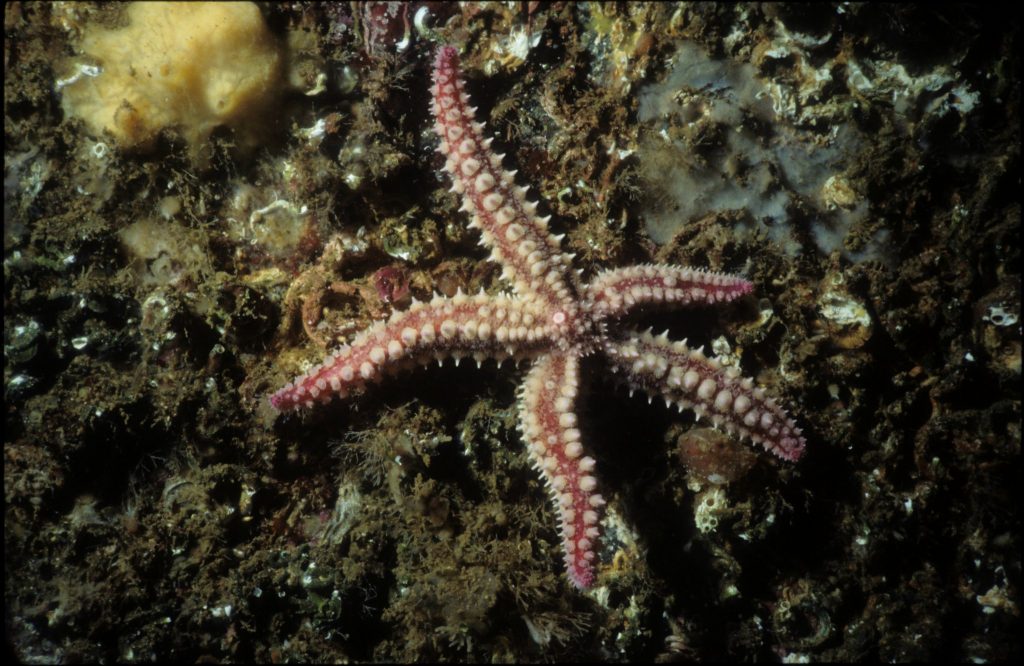

Spiny Starfish (Marthasterias glacialis)

Lesser-Spotted Catshark (Scyliorhinus canicula)

Plaice (Pleuronectes platessa)

Greater Pipefish (Syngnathus acus)

European Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis)

Moon Jellyfish (Aurelia aurita)

Common Eelgrass (Zostera marina)

Oarweed (Laminaria digitata)