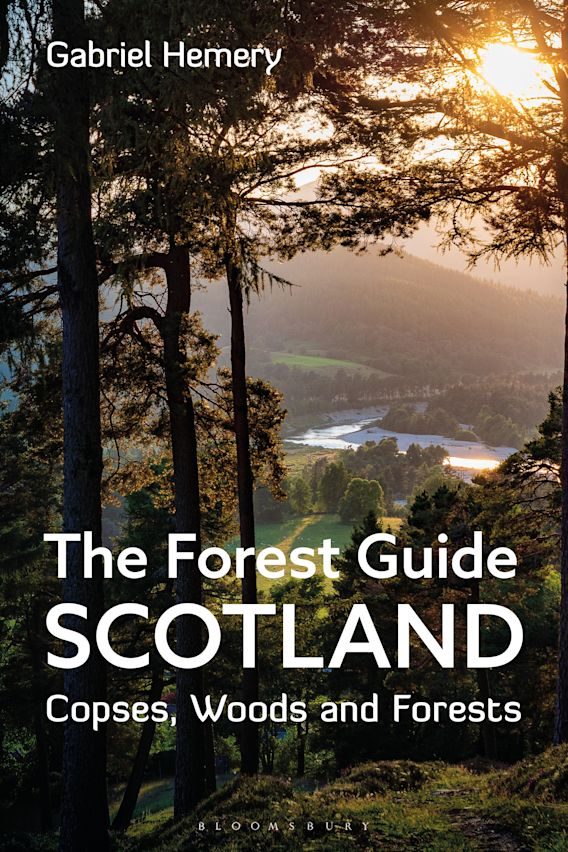

The Forest Guide Scotland is an invaluable guide to 365 of Scotland’s most beautiful, historic and nature-filled woodlands. Ranging from tiny urban copses to sprawling forests, each site is listed by name and location and includes detailed access information and a description of its main features. An essential guide for anyone living in or visiting Scotland, the book is illustrated throughout with the author’s stunning photographs which document the huge variety of plants and animals that can be found within Scotland’s forests.

The Forest Guide Scotland is an invaluable guide to 365 of Scotland’s most beautiful, historic and nature-filled woodlands. Ranging from tiny urban copses to sprawling forests, each site is listed by name and location and includes detailed access information and a description of its main features. An essential guide for anyone living in or visiting Scotland, the book is illustrated throughout with the author’s stunning photographs which document the huge variety of plants and animals that can be found within Scotland’s forests.

Gabriel Hemery is an author, photographer and biologist whose life’s passion is the study of trees, forests and silviculture practices. He is the author of several books including two novels, two short story collections and a poetry anthology. His first non-fiction book, The New Silva, was inspired by horticulturist and diarist John Evelyn’s Sylva, which was published in 1664 and provided readers with the first comprehensive study of British trees.

Gabriel Hemery is an author, photographer and biologist whose life’s passion is the study of trees, forests and silviculture practices. He is the author of several books including two novels, two short story collections and a poetry anthology. His first non-fiction book, The New Silva, was inspired by horticulturist and diarist John Evelyn’s Sylva, which was published in 1664 and provided readers with the first comprehensive study of British trees.

His latest book, The Forest Guide Scotland, is the first of a three part series focusing on the beauty, purpose, history, wildlife and ownership of some of the most extraordinary woodland sites in Britain.

It is clear you have an incredible passion for trees, woods and forests, and they have been the focus of much of your life’s work. Your latest book, The Forest Guide Scotland, is very much aimed at getting the public out into the forests of Scotland. What made you want to write this book in particular?

I’ve wanted to write a guide to the forests of Britain for some time. At a basic level, I felt this would work well alongside my previous work The New Sylva which concentrated more on how to care for trees and forests than their character and location. More deeply, I am concerned by the increasing disconnection between modern society and the natural world. Only through seeing and experiencing, can we hope to inspire understanding and ultimately caring. As a proud forester, I was also keen on dispelling some of the myths about modern forest management, which plays so many crucial roles today in promoting wildlife, improving landscapes, cleaning our air and protecting us from floods, and of course producing timber to replace manmade materials which are harming our environment.

Scotland is a wonderfully diverse place with a beautiful language and cultural history. As someone who embodies the role of artist as well as scientist, did you enjoy the process of finding out about the history, names and traditions of each location throughout your research for this book?

I have loved the landscape and culture of Scotland ever since I first visited as a young boy (when I was so disappointed not to spot an osprey). Researching and conducting fieldwork for this guidebook in so many incredible locations across the country was simply a huge privilege. I learnt a lot about the Gaelic language and the names of trees and landscape features, which I began to recognise as I studied maps. I can’t say my pronunciation of some of them improved however, but everyone I met was very understanding!

Scotland differs from both England and Wales in that it offers its public the ‘right to roam’. Do you feel that restrictions on roaming affect how people perceive and appreciate the wild spaces within their country?

Definitely. Most people probably fear that they may not be allowed to roam in forests, or are unclear of the difference between a public right of way and other forms of access. This undoubtedly means that some people may be put off from exploring woods or forests on their doorstep, let alone when travelling to areas they know less well. While they explore a forest, they may also be nervous that they may be doing something wrong, which will certainly affect their enjoyment.

Writing the guide for Scotland was certainly relatively easy when it came to describing access to forests, while of course explaining responsible behaviour, for example how to avoid disturbing wildlife, being safe during the hunting season, or being a responsible dog owner. In the next guides, which will cover Wales and England, I have a much more difficult task. Many potentially interesting sites are simply beyond reach to the public unless there is a public right of way (e.g. a footpath) or it is part of the public forest estate.

Climate change is a huge issue for every habitat and ecosystem on the planet. What do you think are the main challenges that Scotland’s forests are likely to face in the coming decades? And how well equipped are we to cope with or mitigate these?

Thanks for raising this topic which is personally very important to me, and of course to life on Earth. As a scientist, I have conducted international research on the topic of trees and climate change, and currently I chair a partnership of 16 organisations which seeks to address the urgency of adapting our forests to a changing climate.

Across Britain, our climate will change dramatically, generally becoming wetter and milder in winter, and drier and hotter in summer. Naturally, trees species and associated wildlife will want to migrate northwards to stay within their ideal conditions. Not only does human land use make this very difficult (e.g. competition with agriculture and urban areas) for many species of mammals and plants, but the rate of change is too fast for trees. Trees are individually immobile but do ‘move’ between generations by producing seeds which are dispersed a short distance by wind and other means. If you consider that most trees don’t produce seeds until they are several decades old, it can take a century or more for a tree to move even one kilometre., This is far too slow to keep pace with our changing climate. Scientists believe that our climate zones are moving at up to 5km every year.

There is also a more immediate concern for our trees with increasing threats from pests and diseases. Climate change is making conditions more favourable for many new and invasive bugs and pathogens which affect our trees.

It’s not all doom and gloom. A warming climate will help some trees become more effective at reproducing, provide more suitable conditions for some species which have struggled in the past, and even improve timber yields.

Do you have a favourite forest or woodland from those featured in this book? Or do any stand out particularly in your memory?

Having to choose a favourite forest site from 365 is no easy task! I have so many wonderful memories from my fieldwork for the guidebook. If I were to pick any, I suppose they reflect my own interests in nature and my love of remote places. The Caledonian pinewoods at Glen Quoich near Inverey were stunning and it was encouraging to see so much natural tree regeneration thanks to the effective control of red deer. I was humbled by the passion and dedication of the many community woodland groups across Scotland.

Visiting Berriedale Wood on Orkney was an unforgettable experience, where the trees literally cling to life above the dramatic sea cliffs. I would also have to give a special mention to Inchie Wood near the Port of Mentieth where I had some of the best viewing experiences of my life watching ospreys hunting and nesting.

In 2009 you founded the Sylva Foundation charity, which aims to promote the good stewardship of woodlands through training, knowledge transfer and advocacy. Can you tell us a little bit more about the charity and the work it does?

Sylva Foundation is a charity active across Britain, supporting landowners in managing woods and forests to the best of their ability. We have developed innovative software called myForest which helps them map their woodlands, and complete plans and inventories. Some exciting developments are in the making which will enable landowners to collaborate with scientists to help study environmental change in the woods and forests under their care. Our headquarters is in Oxfordshire where we have a Wood Centre dedicated to supporting people who work in wood to establish thriving businesses. We also run a Wood School helping train a future generation of skilled craftspeople. Readers can find out more at sylva.org.uk.

Finally, as an already well-published author I presume you might have plans for further books? Are there any projects that you are able to tell us about that you’re looking forward to at the moment?

The Forest Guide Scotland is the first of a tryptic, so I am working currently on the guide for Wales (to be published in 2024/5) while the England guide is due out the year after that (all titles with Bloomsbury Wildlife). I am always on the lookout for forest sites to include, and I even have a book patron scheme, so I am keen to hear from potential supporters. Readers can find out more at: gabrielhemery.com/forest-guide.

I am also working on a new book titled The Tree Almanac 2024: A Seasonal Guide to the Woodland World which will be published by Robinson Books this November.

The Forest Guide Scotland was published by Bloomsbury Publishing in April 2023 and is available from nhbs.com.

The Forest Guide Scotland was published by Bloomsbury Publishing in April 2023 and is available from nhbs.com.