***** Still as captivating and entertaining as in 1988

***** Still as captivating and entertaining as in 1988

What if the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs had missed? What might today’s fauna look like then? These are the sorts of questions entertained by speculative zoology, biology’s version of the fiction genre of alternate history. Geologist and freelance author Dougal Dixon is widely credited with launching the modern speculative zoology movement with his 1981 book After Man, a facsimile of which was published in 2018 by Breakdown Press. Fast forward to 2025, and now we have a similar reprint of The New Dinosaurs.

The book follows a similar setup to After Man. It opens with introductory material before presenting the new dinosaurs. The point of the introduction is that, although the scenario is fictional, it is developed according to sound scientific principles. Dixon thus introduces you to the basics of palaeogeography, zoogeography, and Earth’s main habitat types. He also explains what dinosaurs are, how they went extinct in our world, and how the tree of life took shape in this alternate universe where they did not. Some of this material has been updated, but I will get to that.

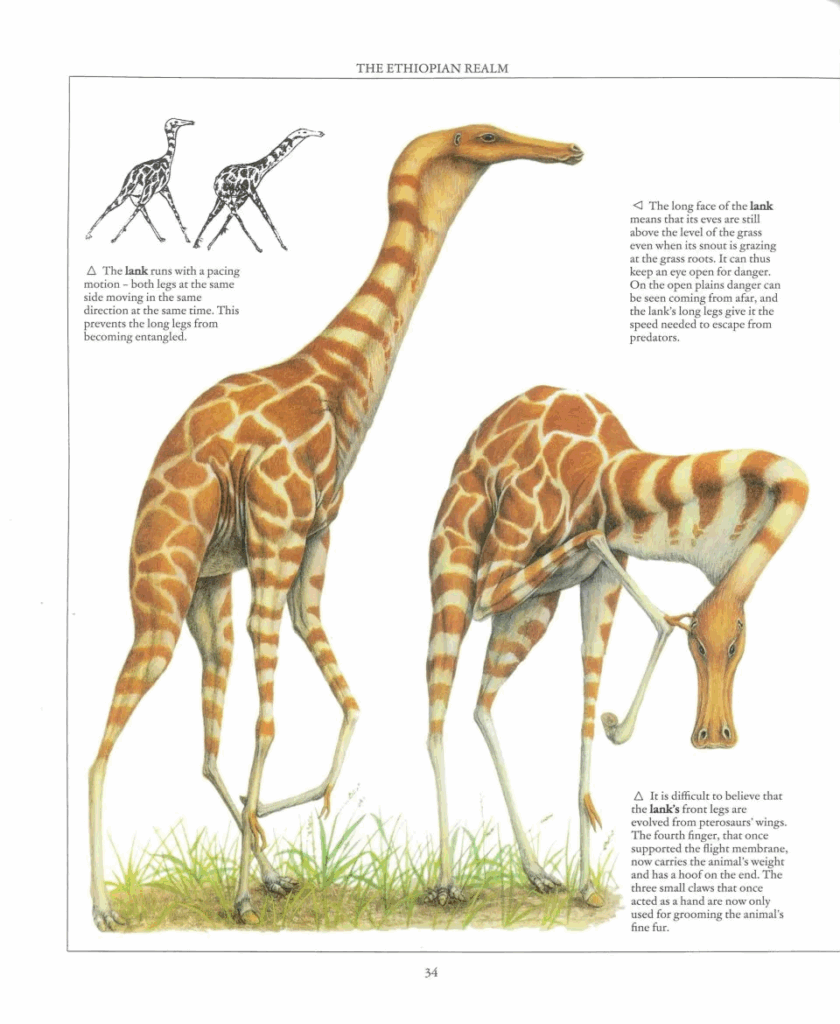

The stars of the book are, of course, the critters that Dixon has dreamt up, and what a wonderful menagerie they are. The artwork really helps bring them to life. Every creature receives at least one life reconstruction in colour showing the whole animal in a natural setting, with some receiving additional smaller drawings in colour or b/w to highlight anatomical characteristics or behavioural sequences. Twelve people were involved with this book. Two, John Butler and Philip Hood, are return guests; the other ten are new collaborators. With such a large number of illustrators, inevitably, some appealed more to me than others. Butler and Hood’s work is again superb, but I also really liked the work of Steve Holden (he drew the Cutlasstooth on the front cover and the Lank, on which more below) and Martin Knowelden (he drew the Paraso, a wading pterosaur, and the Whulk, on which more below). Some of the depictions of sauropods are rather dumpy and have not aged terribly well, betraying the fact that this *was* 1980s palaeoart, but, by and large, I think the depictions hold up well while exuding a certain nostalgia.

So, how has life evolved in this alternate universe? The mammals have remained small. With the evolution of grasses, numerous dinosaurs and pterosaurs have become grazers. Coelurosaurs and hypsilophodonts are two dinosaur groups that have left many descendants, the former notably spinning off a successful and diverse group that became arboreal: the arbrosaurs. The pterosaurs have been similarly successful and evolved into many surprising forms, occupying some of the niches taken by birds in our world, and losing flight on multiple occasions.

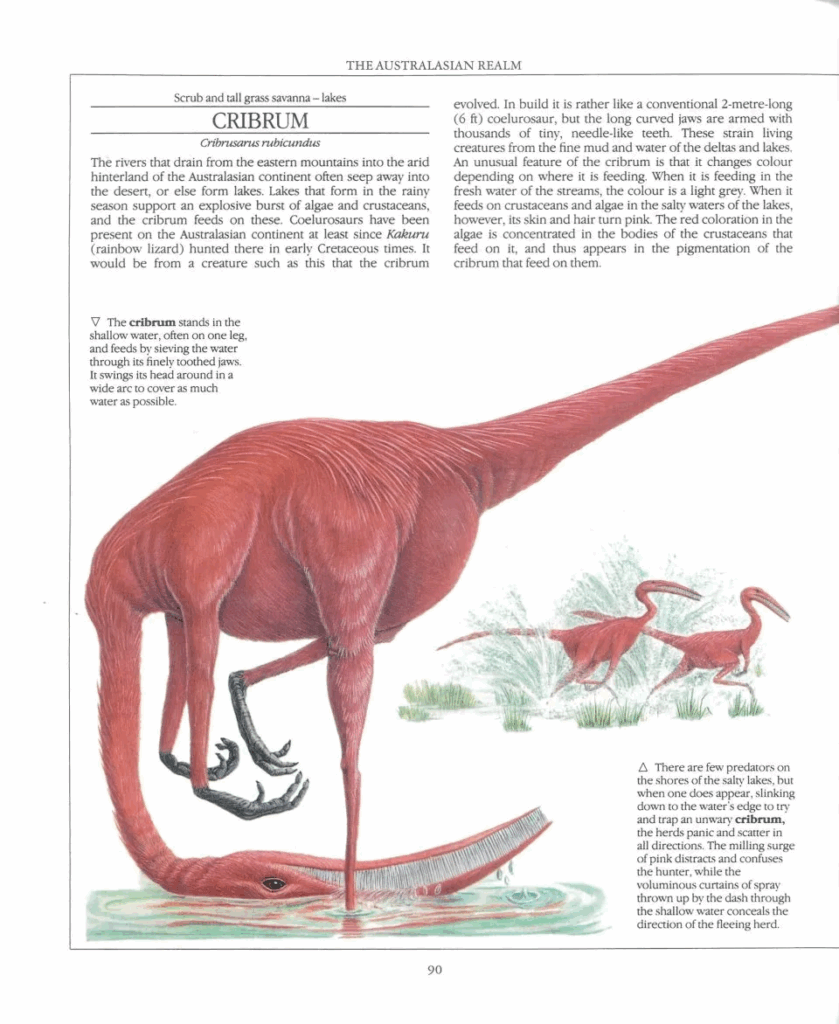

Some creatures look very familiar. The above-mentioned Lank, a flightless grass-eating pterosaur, closely resembles our giraffe; the Whulk, a filter-feeding pliosaur, takes the place of our baleen whale; the Cribrum, a theropod descendant, is an unapologetically pink filter-feeding flamingo; and the Nauger, an arboreal dinosaur that bores into wood, resembles our Pileated Woodpecker (with Dixon even winking at the reader by speculating that, in another world, this niche could conceivably be taken by a bird). Though these creatures make the point that we should not be surprised by convergent evolution, the book contains more than just like-for-like reptilian replacements of our mammals and birds.

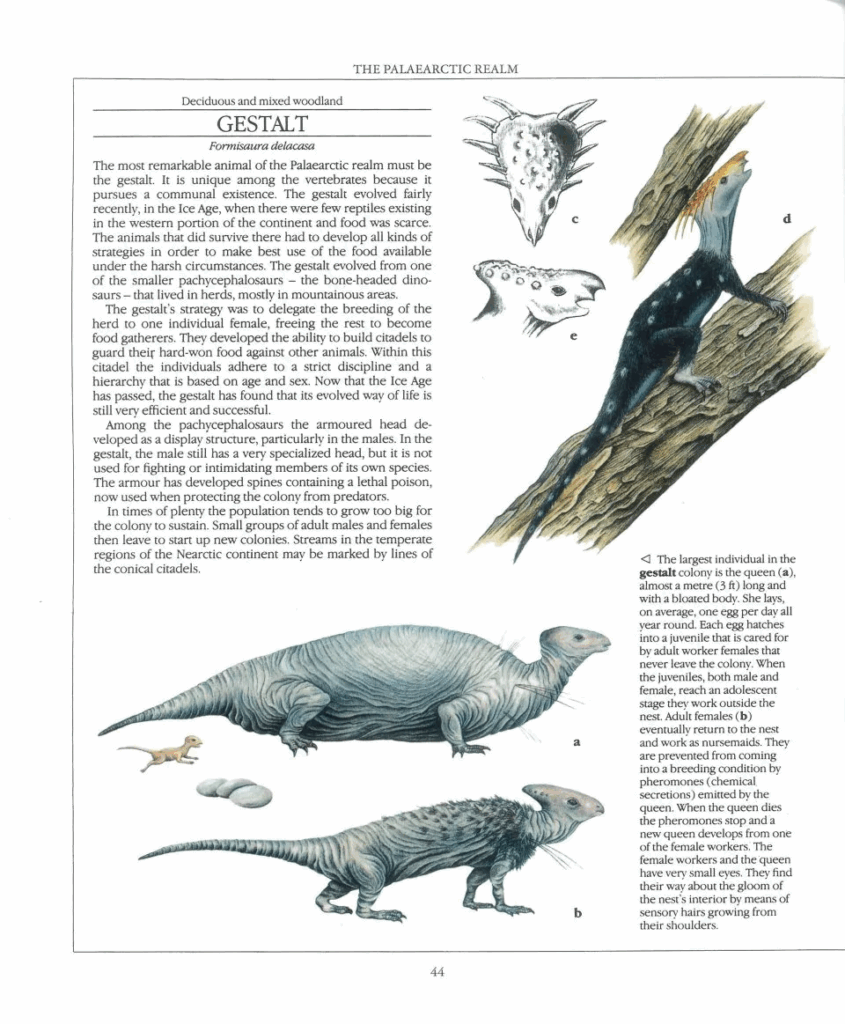

There are some really interesting mashups. The Gestalt, which evolved from a pachycephalosaur, has become a nest-building dinosaur that lives in colonies in which only one female queen breeds. In both appearance and behaviour, they combine elements of naked mole rats, beavers, and ants. The Crackbeak, an arbrosaur, has developed the arboreal physique of a spider monkey and the seed-cracking beak of a toucan.

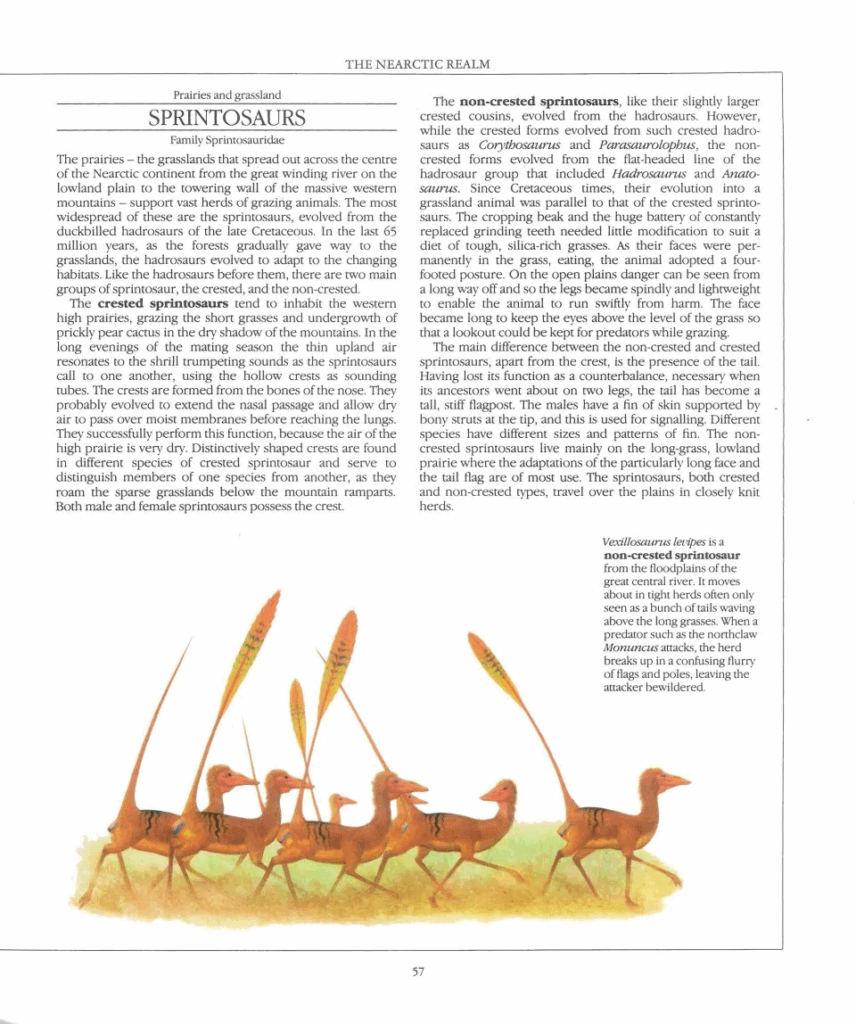

Some species sport anatomical features that at first blush seem out of this world, until you realise that, actually, they are very much of this world. The Nauger’s long second finger used to winkle larvae out of holes in trees? The Aye-aye of Madagascar has it too. And surely the Northclaw’s arrangement of having an enlarged claw on just one hand is… Ah, yes, the fiddler crab. Mind you, life has found unexpected solutions in Dixon’s world. One recurrent feature is stiff tails, held erect like flagpoles, with the non-crested sprintosaur even called – I see what you did there, Dixon! – Vexillosaurus. Outside of squirrels in our world, this strikes me as very uncommon. Three arboreal species have hands where both outer fingers are opposable, which is also found in our koalas. As Desmond Morris writes in the foreword, it is the close observation of biological principles and outliers that imbues these fictional creatures with a high degree of realism. This is as much entertainment as it is a serious exploration of biology by means of made-up animals.

There are two further elements worth discussing. First, the quality of the reproduction is overall good, though, as with After Man, perhaps a tad on the dark side: the surface texture on the black Tromble and Balaclav is hard to see. Second, Dixon has again made corrections to the text, which have been printed in a slightly different font that can just be made out. The biggest changes are made to the introductory material. The sections on the extinction and definition of dinosaurs have been rewritten to reflect advances in our knowledge, and the classic tree-like diagram on pages 12–15 has been completely redrawn. The biggest change to the creature section is minor: a small box now mentions that stegosaurs were extinct by the early Cretaceous, in line with modern taxonomy, while in the 1988 version, stegosaurs survived on the Indian subcontinent until 2 mya. Beyond this, minor corrections have been made to some taxonomic affiliations, the date of the end-Cretaceous (now 66 Ma ago), and references to the Tertiary (now Cenozoic). However, this process could have done with a round of proofreading as references to 65 Ma and the Tertiary still abound, while the example of a modern cladogram on p. 10 is unfortunately full of spelling errors. It seems the drawing of the Kloon skull on p. 96 was accidentally left out, even if the label describing it is still present. Arguably, these are minor errors.

Overall, The New Dinosaurs remains an incredibly entertaining romp into speculative zoology. If you possess a copy of the original, you have a nice vintage book, and I would not rush out to replace it. No bonus material has been included. However, for all of us who never bought this book upon release and were condemned to the inflated prices on the aftermarket, it is a great joy that Breakdown Press has made this book available again.