NHBS is delighted to be working with Waterhaul, a company turning harmful marine debris into valuable resources. Their commitment to tackling ocean plastic and promoting sustainable practices aligns closely with our own mission to protect wildlife and the natural environment.

NHBS is delighted to be working with Waterhaul, a company turning harmful marine debris into valuable resources. Their commitment to tackling ocean plastic and promoting sustainable practices aligns closely with our own mission to protect wildlife and the natural environment.

Earlier this year, NHBS arranged a beach clean using Waterhaul products, giving us first-hand insight into their quality and effectiveness. After seeing them in action, we’re excited to now offer Waterhaul’s beach cleaning range through NHBS.

To learn more about the inspiring work behind the brand, we spoke with Jon Green at Waterhaul and asked a few questions about their mission, processes, and impact.

You primarily create your products from recycled “ghost gear”. What is ghost gear? and have you set your sights on any other forms of marine pollutants for future projects?

‘Ghost gear’ refers to any fishing gear that has been abandoned, lost, or discarded in the ocean. Once separated from fishing vessels, this gear continues to drift in the ocean, entangling marine life and damaging habitats. Ghost gear is a subset of marine litter but is particularly harmful due to it being designed specifically to trap and kill marine animals, combined with its extreme durability.

Unfortunately, around 640 000 tonnes of lost or discarded fishing gear end up in our oceans every single year, making it the most harmful and abundant plastic – there is certainly enough of it to keep us busy! That being said, in the past we have worked with other forms of plastic, for example our ‘ReTask The Mask’ campaign where we recycled PPE from the NHS post-COVID-19 into litter picking components.

How and where do you find the nets needed to supply your products?

Being a team of ocean users all passionate about protecting what we love, we often can be found out and around the Cornish coastline physically collecting reported ghost gear ourselves; from remote corners requiring boats, paddling or swimming to in plain sight on some of our busiest beaches following storms.

As well as collecting ourselves, we have a dedicated Impact & Recycling team who have established strong relationships and partnerships with local fishermen, harbours, organizations and waste management companies such as Biffa, providing an end-of-life solution and preventing the gear ending up in landfill.

We often hear stories of plastic packaging that has lasted for an age in our waters, only to wash up in recent times. Is there a particular piece of netting that stands out from your time working with marine plastic?

The most prominent one/example that comes to mind happened on September 21st 2023 where the Raggy Charters crew spotted a juvenile humpback whale in Algoa Bay, South Africa, exhausted and entangled in fishing gear and fighting for its life.

The whale was struggling under the weight of heavy plastic ropes cutting into its flesh as well as two large orange buoys, a small yellow buoy, and a huge amount of 20-mm nylon cable wrapped around its caudal fin.

A rescue operation, led by the South African Whale Disentanglement Network took hours of painstaking effort involving multiple rescue boats and a coordinated team where they were able to free the whale who swam away, shattered but alive.

The ghost gear that ensnared the humpback was recovered and through collaborative links with the World Cetacean Alliance (WCA), made its way to us, where we saw an opportunity to create something unique and share this near-tragedy as part of our ‘Rescue to Recycle’ Campaign. An initiative that transforms harmful marine debris into products that drive change and supports ongoing conservation efforts.

What percentage of your total product is made from ocean-reclaimed materials?

100% of all plastic components across our entire product range are made from Traceable Marine Plastic (TMP), our material feedstock derived from lost, abandoned and discarded fishing gear. Our eyewear frames are also made 100% from TMP.

Do you partner with any marine conservation or environmental organizations?

Waterhaul was founded with a background in and ethos of marine conservation and environmental direct impact, ultimately initiating the mission we are on. We are incredibly proud to be supported by and have partnered with organizations such as Surfers Against Sewage, The Wave project, Sea Shepherd, The RNLI, Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Canal and River Trust, and many more.

Can you explain the process of transforming ocean plastic into your final products?

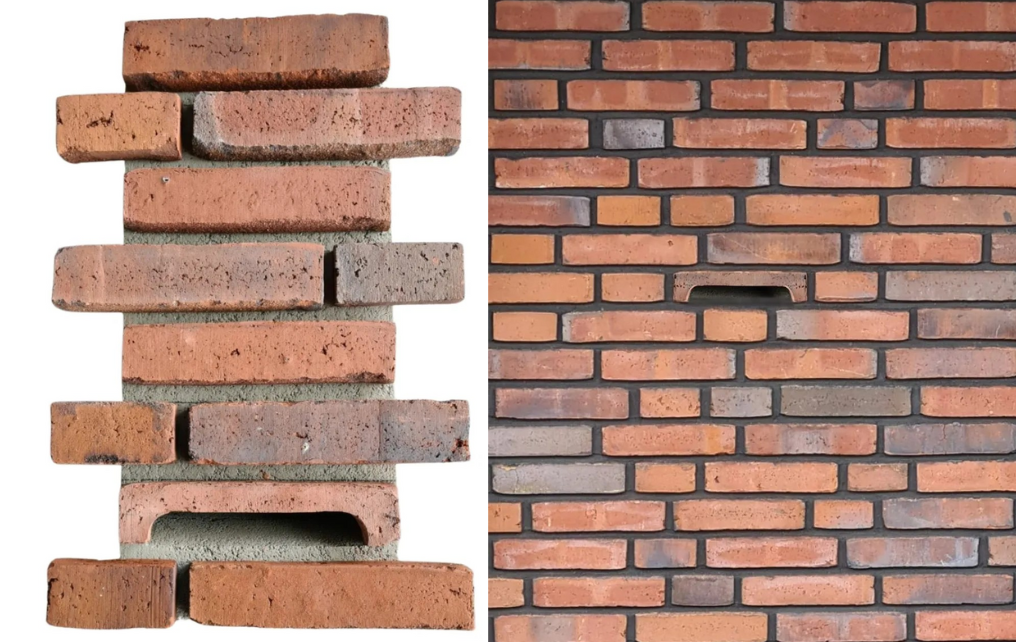

Every single piece of ghost gear, whether collected by ourselves or the end-of-life fishing gear we have received from the source, is taken to our processing unit here in Cornwall.

The gear is then separated by polymer type and recycled in the UK through a mechanical process of shredding and washing. The plastic is then extruded into pellets and becomes our fully traceable raw material, Traceable Marine Plastic (TMP).

We then injection mould this plastic into our range of purposeful products. This is the stage where we give new value to plastic ‘waste’. Our impact is driven further by our extensive network of partners, from stockists to product partners and more.

What’s the best way for someone to get involved in helping your mission, any tips for how everyone can make a difference?

Aside from the conscious purchasing of products that make a direct impact and questioning the materials of where our products come from, getting out there is the most efficient way of making a difference. Grab a litter picker and whether it’s a 2-minute beach clean, a litter pick around your nearest green area or picking up rubbish you pass on the street, it all makes a huge difference in protecting our planet’s ecosystem and wildlife! Spending a few extra minutes to sort out recycling from domestic waste will also play a huge role. Finally, talking about and sharing stories on this often-overlooked topic will also spark conversations and inspire others to go out and do the same thing!

Browse the Waterhaul products available through NHBS here

Visit the Waterhaul website to learn more about their work here

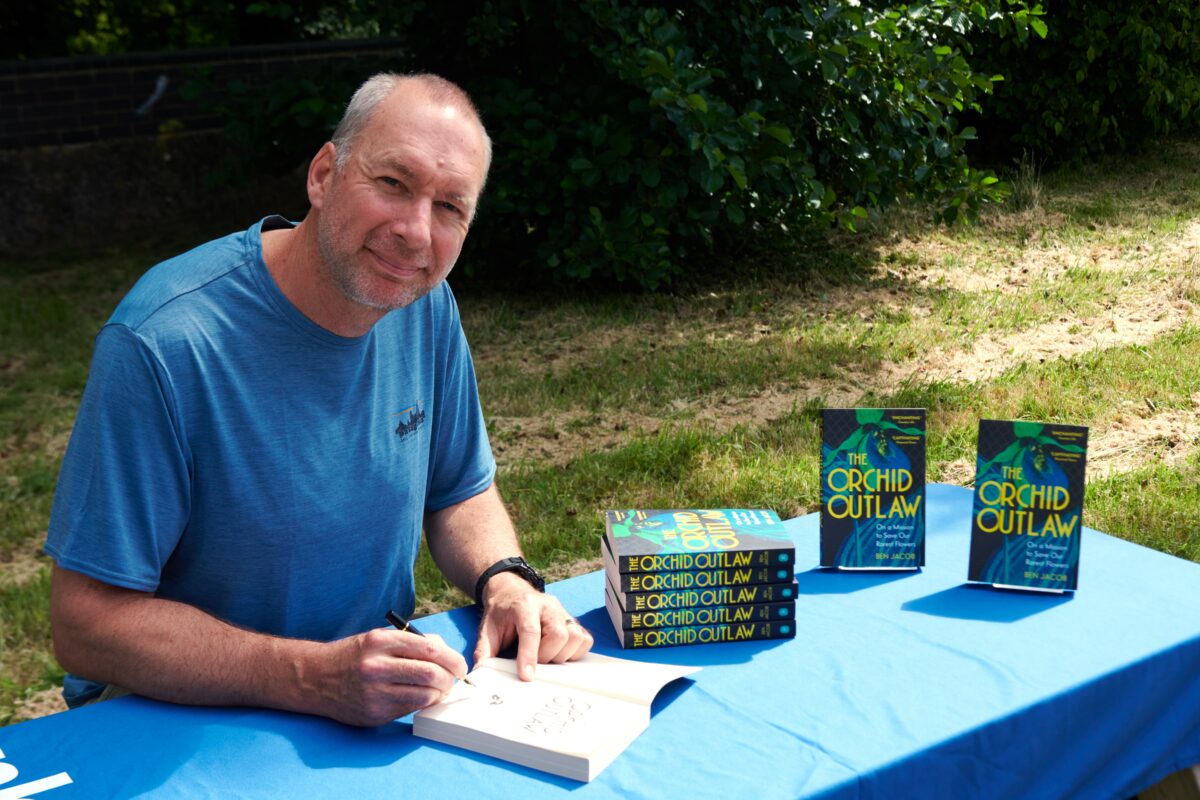

Ben works as a University lecturer by day, and as a clandestine ecologist, conservationist and Orchid-saviour by night. It is always a pleasure to meet the authors behind our books, particularly those who are adopting their own approach to nature restoration and conservation, and we were delighted to have the opportunity to talk to Ben in person about The Orchid Outlaw and have him sign our books. We discussed how he first became interested in Botany, his thoughts on the Right to Roam movement, what he hopes the reader can learn from his book and more. Read the full author interview on the Conservation Hub.

Ben works as a University lecturer by day, and as a clandestine ecologist, conservationist and Orchid-saviour by night. It is always a pleasure to meet the authors behind our books, particularly those who are adopting their own approach to nature restoration and conservation, and we were delighted to have the opportunity to talk to Ben in person about The Orchid Outlaw and have him sign our books. We discussed how he first became interested in Botany, his thoughts on the Right to Roam movement, what he hopes the reader can learn from his book and more. Read the full author interview on the Conservation Hub.